A Day in Watts in Search of JuJu Watkins

The USC women's basketball superstar and the historic Los Angeles neighborhood are deeply intertwined. How the legacy of Watts lives on in her game, on and off the court.

I stand in the shadow of the Mother of Humanity monument awaiting the arrival of Tim Watkins. It’s a stereotypical January day in Los Angeles. Where my home city of Denver is approaching single digit temperatures, it’s so nice in L.A. that I’m burning up in a sweatshirt. The monument reflects the sun and stands in stark contrast to a clear blue sky. It was dedicated here in 1996 and created by sculptor Nijel Binns, who sought to honor the African woman as the mother of all humanity. It’s an apt starting point for the journey I’m about to take. For this Sunday is about finding JuJu Watkins, the USC women’s basketball superstar, who still calls this neighborhood home. As I sit in the parking lot, I check my phone to look at tip-off times. JuJu, of course, isn’t actually here in Watts. Instead she’s over a thousand miles away in Bloomington preparing for a game against the University of Indiana.

But the act of finding someone can take on a few different meanings and it’s on this day that I’m hoping her grandfather Tim can be my guide. He pulls up in a pickup, we shake hands, introduce ourselves and take a walk inside the home of the Watts Labor Community Action Committee, or WLCAC, in search of JuJu Watkins.

Phoenix Hall & The Henrietta Marie

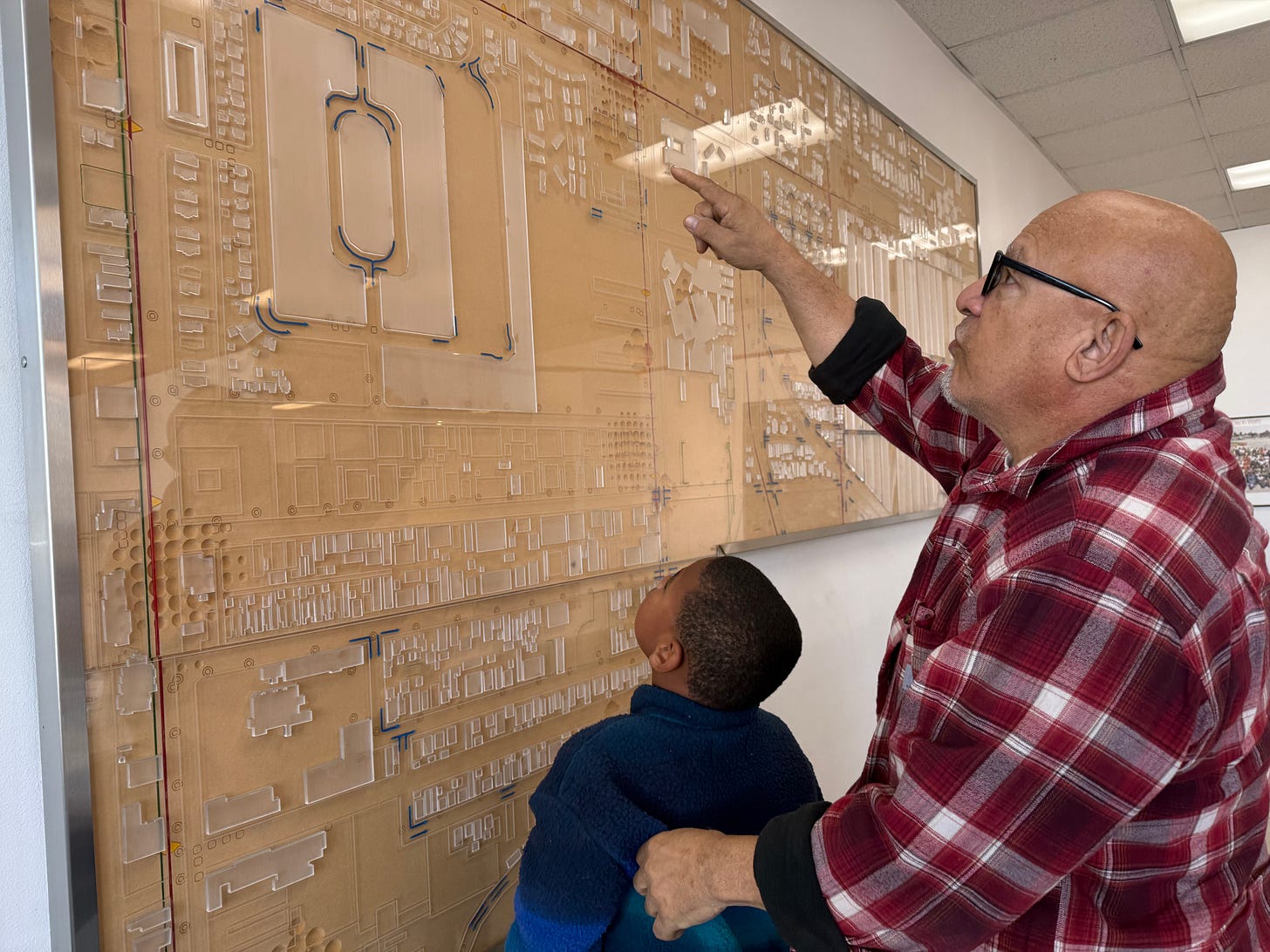

We begin in Phoenix Hall. Think of it as an ‘everything space’ for the community. A family is setting up for a child’s birthday party as Tim, myself and his grandson — who will be a spectator on our tour — prepare to walk through the WLCAC’s Civil Rights Museum. Generations of Watkins children have spent time here since the family patriarch, Ted, founded the organization in the wake of the Watts Rebellion of 1965.

In many ways, a Phoenix is representative of Ted Watkins, his family and of the WLCAC itself.

“He was unbelievably strong,” Tim says of his father Ted. “Some people said he was unhumanly strong.”

That description was applicable in a physical, mental and emotional sense. At the age of 13, Ted was living in Meridian, Mississippi during the height of the Jim Crow era. While walking down the street one day, a Western Union mail carrier passed by and demanded Ted make way and move off the sidewalk. Wearing a pair of shoes given to him, a pair that were unique in that they didn’t have holes in them, Ted refused. He didn’t want to dirty the shoes by stepping down into the mud. A fight broke out and a young 13 year old Watkins broke the mail carriers’ ribs. His parents told him he needed to flee Meridian as word was spreading around town that Ted was going to be lynched the next day.

“He did not want to leave Mississippi,” Tim explains. “He wanted to fight.”

It was the type of attempted subjugation that whites employed to desperately maintain a power dynamic that had been in place since the colonization of what is now known as the American South. A history displayed in the first exhibit of the WLCAC’s Civil Rights Museum.

“This is really just about people being aware of what was in the past,” I’m told as we walk into a recreated hold of a slave ship, “so that going forward we start to see it when it starts to — if it starts to — rear its’ head again.”

The ship recreation is of the Henrietta Marie. It was discovered in 1972 off the coast of the Florida Keys and there's been evidence found that its’ primary purpose was to traffic slaves from Africa to the United States, one of the few wrecks ever identified as having that sole purpose. To recreate it, legendary movie director Stephen Spielberg donated the outer side of a ship, which was used in his 1997 film Amistad, while the interior was donated by movie director Joel Marsden who used it in the film Ill Gotten Gains. Within the darkened hold are plaster casings of people — real moldings modeled by students in Watts — meant to give museum goers an understanding of what a journey in the Atlantic Passage was like.

“It’s meant to be foreboding,” Tim says. “It’s not cute by any means.”

The feeling is palpable. It’s not comfortable to close one’s eyes and picture the concept played out with actual souls instead of plaster moldings of people. But while the intention isn’t to foment resentment about the legacy of slavery, Tim explains, it’s meant to display that this is an experience from the not-so-distant past.

As we walk out of the ship, we approach a red line painted on the floor in front of a doorway. It’s a symbolic line of the entry to prison, a legacy extension of the bondage of the 16, 17 and 1800’s. Classes of kids come through this exhibit, he tells me, and the staff uses it as a means to explain that there are structures in place that can put Black Americans right back into that past and that the goal for those kids, above all, is to not return to it. To not cross that line and make the right choices to survive and advance in society. To fight.

Tim opens the door to our next exhibit, what he calls Mississippi Delta Road, where we start to get closer to the answer that I’ve been looking for.

Mississippi Migration

Inside the next room, there are dozens of artifacts pulled straight out of the 20th Century. A 1953 Pontiac is parked along a makeshift road of green astro turf and a small structure has been built, meant to symbolize a juke joint and community gathering place for those that lived in the Jim Crow south. The exhibit draws a clear line from chattel slavery to forced segregation, the type of environment his father left at the age of 13.

As Ted hastily prepared to leave home forever, he packed a bag with some clothes and a couple newspaper clippings and got on a train from Vicksburg to New Orleans, and then on another from New Orleans to Los Angeles. He began his life anew in California, reborn in more ways than one. He now had to make his way in a city that was welcoming more and more southern black families in what would come to be known as the first Great Migration. But the dream of a western land free of the racism that permeated southern culture didn’t line up at all with the reality.

“You quickly discovered that covenant restrictions required you to only live in certain areas, and even in Watts, you weren’t allowed to live next to white people,” Tim says.

Housing covenants were challenged in courts in Los Angeles because a family from Watts, Albert and Texanna Laws, bought a house on the ‘demilitarized zone’ of 92nd Street where the black neighborhood ended and the white neighborhood began. They endured years of lawsuits, threats and allegedly, according to Tim, a burning cross on their lawn courtesy of L.A.’s branch of the Ku Klux Klan.

It was during this period of time that Ted started to make his way in Los Angeles, though the period of time between ages the 13 and 19 are still a mystery even to his own son. Even now, Tim can’t find anyone that knew him before his father got married for the first time at age 19 and fathered Tim’s two older brothers. At 22, Ted suffered a major tragedy as his first wife died from Tuberculosis. Some time later, after covenant restrictions in Los Angeles had been lifted, he met his second wife in a Bank of America on Broadway in the Manchester area of L.A.

“I think that the connection of my father marrying my white mother had to be part of his defiance,” Tim says. “[It] had to be part of his determination to go against the grain. He wasn’t a community organizer at that point. He wasn’t a change agent. At one point, he became one. But he was not. My mother was.”

Bernice Watkins spent part of the 1950’s writing letters to President Harry Truman and later Dwight D. Eisenhower admonishing the administration for considering the use of a nuclear weapon during the Korean War. She was involved in a protest on behalf of Bank of America workers to allow employees to have a lunch break.

She and Ted got into community organizing in the 1950’s when the family moved into the Palm Lane Housing Projects. Tim was born a couple years later in 1953 and the family never left Watts after that. Ted and Bernice moved to another part of the neighborhood, a block where Tim still lives now and next door to the house his son Bobby, his wife Sari and Bobby’s daughter Judea would later live.

“Don’t move, improve,” Tim says, echoing the now famous phrase associated with his father.

As we maneuver past the Mississippi Delta Road exhibit and leave the era of Jim Crow, we pass a collection of advertisements from the pre-Civil Rights era. Infant spoons, Columbia vinyl records and childrens books reiterating and nostalgically nodding to the idea of a group of people being subservient to the other.

In many ways, it’s a coda to all of the exhibits we’ve walked through to this point. From the Henrietta Marie to Mississippi Delta Road, it all led to a consumeristic longing by white Americans to return to, as Tim puts it, ‘the good old days when things were easy’. Suddenly, as we prepare to entire an extensive photo exhibit centered on the Civil Rights era and the genesis of the WLCAC, everything starts to come into focus. I realize that there’s a reason Tim is laying out all of this history before we even discuss JuJu. The evolution of the exhibits mirrors the evolution of Ted Watkins, the Watkins family and now we were about to take the leap towards the present day.

Civil Rights and Sports

The final exhibit within the museum is essentially a photo gallery of some incredibly rich L.A. history. Everything from the Watts Rebellion of 1965, which spurred the creation of the WLCAC, to major civil rights moments in Los Angeles as well as nationally, is noted here. There is a massive collection of Howard Bingham’s photos of the Black Panthers from the six months he spent with the organization. Even the story of these photos is noteworthy within the history of defiance and solidarity that the WLCAC’s museum aims to display.

Bingham was commissioned by Life Magazine to follow the Panthers. Organization leader Eldridge Cleaver, who was serving time in jail, granted Life the chance to do the story but only if Bingham, whose work Cleaver knew from the LA Sentinel, was taking the photographs. Writer Gilbert Moore was commissioned to handle the actual feature. After three rewrites, Life and Moore reached an impasse. They wanted an exposé and Moore would not oblige.

“I knew what they wanted,” Moore would write later, “but I was not prepared to cough it up. The price, psychologically speaking, was too high.”

He would later resign from the magazine. Bingham’s photographs would not see the light of day until his book about his time with the organization was released in 2009. At the WLCAC, pictures of Cleaver, Bobby Seale, Huey Newton, Angela Davis and others are on full display.

These individuals were activists, agitators to a status quo rooted in that same nostalgic desire to return to a place of subjugation and inequality. But alongside them were athletes and entertainers. Cassius Clay and Lew Alcindor became Muhammad Ali and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, respectively. Tommie Smith and John Carlos worked with Dr. Harry Edwards to create one of the most powerful public protests in sports history. Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte and Eartha Kitt were major figures for advocacy in Hollywood.

“They tried to balance their professional experience with their community experience,” Tim says. “At the end of the day, that generation fought for my generation to be able to do that without fear of repercussion.”

It’s at this point that I start to wonder about the weight of expectation and whether or not everything that exists within this place had been placed upon his granddaughter’s shoulders. The WLCAC is just as much JuJu’s home, after all. She, like her father before her and his father before him, spent her days here. But the intention of Ted and eventually Tim was never to push their children to take on the weight of activism and organizing. It was to allow them to find it organically if they chose to.

“It’s not transcendental,” explains Tim. “You get it subliminally. It’s in the background of whatever you’re doing and, over years, you absorb all those little pieces and you end up like me.”

From what I can glean, JuJu has indeed absorbed what the WLCAC is, especially considering how often she still comes here and frequents the center. Her fifth grade graduation was in Phoenix Hall, her siblings had summer jobs here and everything in their orbit would come back to the area in some way, shape or form.

What Tim sees is a shade of his father in the girl he still lovingly calls Judea.

“My father was after justice,” he mentions. “He did what he did. I’m doing what I’m doing. And my granddaughter already told me, what if nothing else was in that way? What would she be doing doing? ‘Seeking justice.’ That’s what’s in her, whether it’s DNA or her psychological structure, that what came out of her mouth.”

In fact, there was a day that Tim remembers about a young JuJu telling him she wanted to be a judge. So he went to U.S. congresswoman Maxine Waters, whose 43rd district encompasses nearly all of Watts. He told her of his granddaughters’ potential aspirations and so the two decided it might be worth her meeting an up-and-coming federal judge: Ketanji Brown-Jackson.

That meeting never materialized as JuJu’s basketball stardom ascended into a new stratosphere and Tim is completely fine with that. In his eyes, the weight of expectation when it comes to community organizing and civil rights advocacy is something his granddaughter doesn’t need to burden herself with at such a young age. In fact, his belief is that everything will come in due time at at her own pace.

“Judea has to enjoy life for a minute,” he says, bringing our hour and a half in the museum back to our original premise. “Get out there, feel the world. Do some good, learn about your history and then she can make a decision about whether she wants to be an activist.”

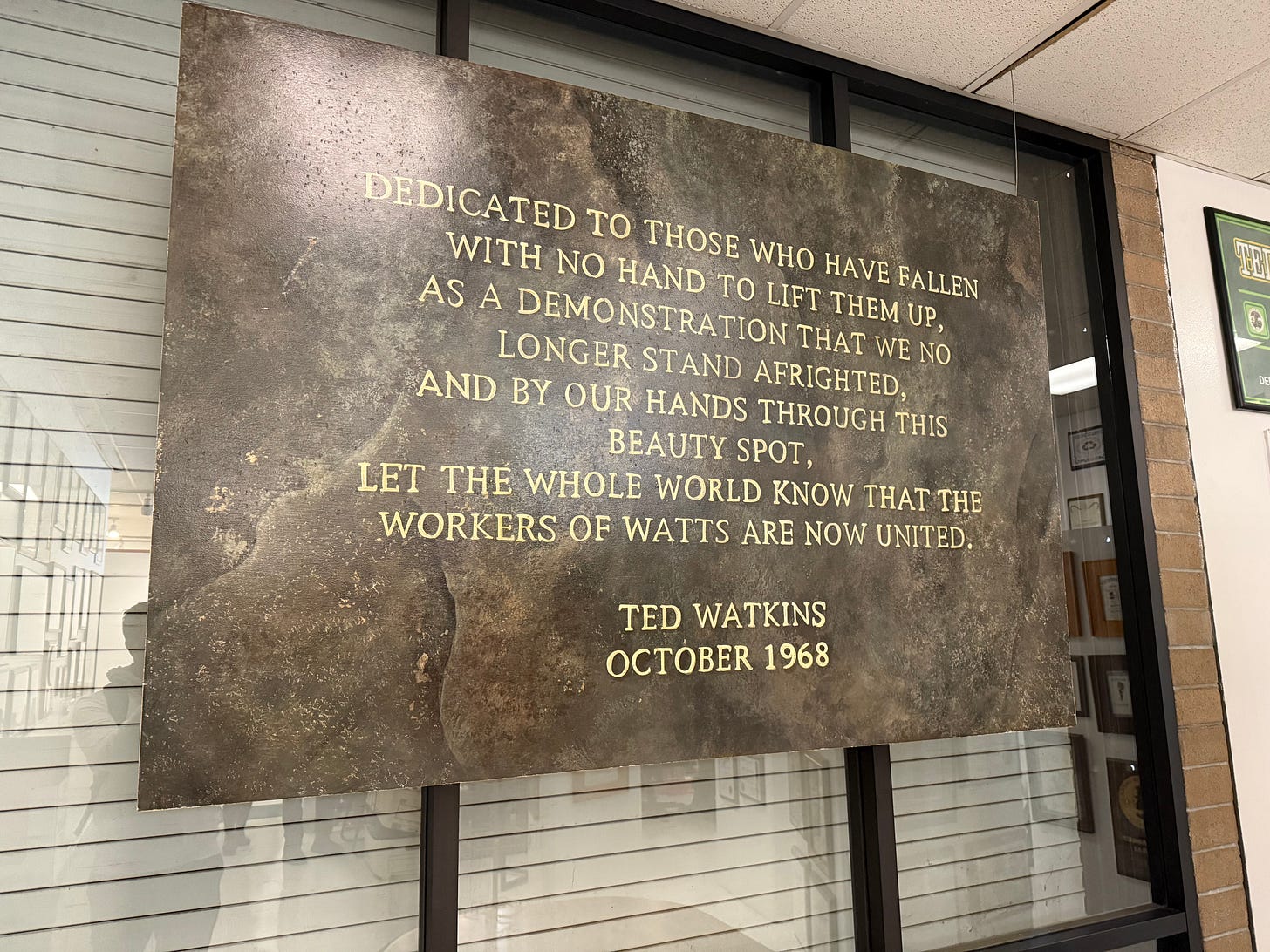

As we settle on a notion of patience, I notice a sign with a quote from Ted Watkins in one of the back rooms of the building. I ask Tim about one particular passage of the quote and he takes me somewhere special: the vault of the WLCAC, to show me something wonderful. A way to find JuJu Watkins in Watts at long last.

The Vault

The sign I see is inscribed with the following quote…

Dedicated to those who have fallen with no hand to lift them up.

As a demonstration that we no longer stand affrighted,

And by our hands through this beauty spot,

Let the whole world know that the workers of Watts are now united.

Tim wonders aloud why that particular sign catches my interest. It’s just a really powerful statement, I reply. So we head back to the vault. This is a place where some of the most treasured pieces of the WLCAC are kept. We walk into the door of a cramped room lined with file cabinets and antiques on shelves and walls to the ceiling. On one end of the room, Tim points to a worn bag. It was the bag Ted took with him when he left Meridian at 13 years old to come to Los Angeles.

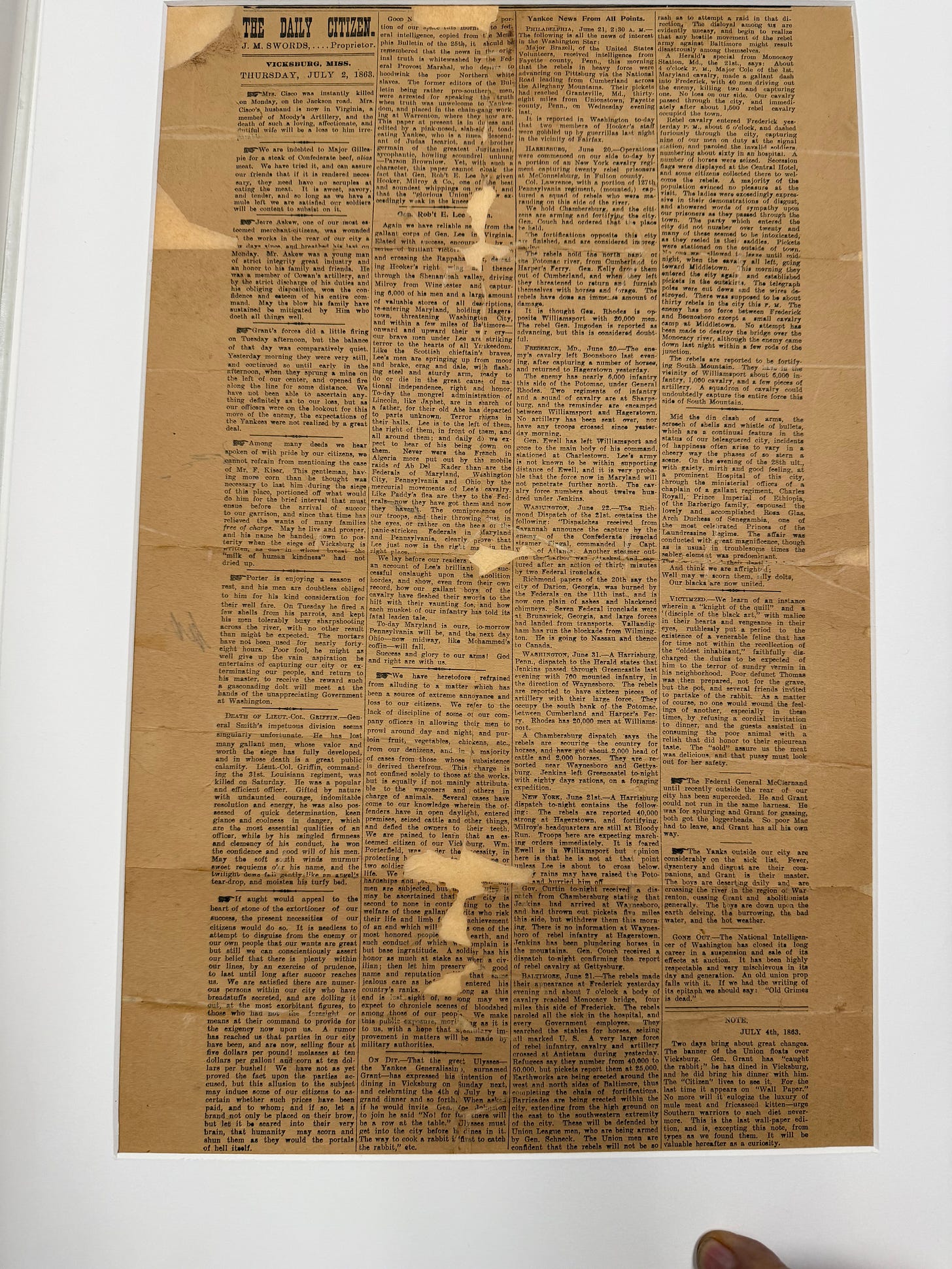

He then instructs me to open a large Manila folder to look at what appears to be an old newspaper. It’s printed on cloth, a reflection of the times and circumstances in which it was produced. The paper is the final issue of the Vicksburg Daily Citizen, dated July 2nd, 1863. With the Union Army on the doorstep of a watershed victory in the Civil War, the paper produced one last time. A small write up appears about halfway down on the far right margin, detailing a party held that night by a group of African nobles from Ethiopia and ‘Senegambia’.

And to think we are affrighted ; well may we scorn them, silly dolts,

Our blacks are now united.

Ted took this newspaper, which he found in his house in Mississippi, with him to Los Angeles. 105 years later, during a year in which the Civil Rights Act was signed, he hearkened back to a news note on the eve of one of the Union’s greatest wins over the Confederacy, twisting the words of a writer who couldn’t understand why black individuals in Vicksburg were celebrating their impending freedom and turning it into a modern day clarion call to those that wished to see such joy in possibility again.

A patient act of defiance, punctuated by the victory of building a community.

Today, the WLCAC is a focal point of Watts even as the area around it begins to change and morph. The group owns housing projects that provide equitable opportunities for those within their community. They employ people in the neighborhood, from those needing a second chance to others wanting to make a difference. Phoenix Hall hosts events and sees a consistent visitor, JuJu, who takes time out of her schedule to pay it forward in Watts.

While society seems to prioritize expedient and sometimes solely aesthetic answers to major social problems, Tim wants his granddaughter to be patient and take her time. She need not be in a rush to fit a certain label and, when she chooses to do so, will have the tools at her disposal to make the changes she may want to see.

“Judea’s poise, her elegance, her intellect, she understands that she’s in a complex world,” he says,” but she deserves to live a very simple life. And she does that better than anybody I know. What I witness is it’s not complicated for her. She ain’t trying to hurt nobody. She’ll help where she can help. She doesn’t have to create that history. She lived it. Where does she live? Watts.”

One last ride around Watts

“Whenever I finished my homework, I was able to go [to the back of the house] and that’s where I spent most of my time, with my brothers and my Dad,” JuJu tells me over the phone. “It was just a way for us to connect as well. It was just really therapeutic.”

Tim would spend nights looking into the back area between his and his son’s house and see his granddaughter playing basketball. Soon, she would be playing at Ted Watkins park — on ‘a janky court, all concrete’, she remembers — where eventually a mystique about her grew. After two years at Windward School, JuJu ended up at Sierra Canyon and, bolstered by the proximity to star power that living in Los Angeles provides, she soon became a household name in Southern California.

She signed a deal with Nike while still in high school and was the first athlete of that level to sign with Klutch Sports for NIL representation. Every school with a functional women’s basketball program wanted her to wear their team’s colors. But the call of home was strong, the phrase ‘Don’t move, improve’ stuck in her head when deciding between Stanford, South Carolina and USC.

In a way, many things revolving around JuJu returns to Watts and most historical pieces of Watts are a reflected in JuJu.

After our walk through the WLCAC, Tim and I drive through the mustard colored apartments of the Nickerson Gardens housing projects, one of the largest in the city, before stopping at Hawkins House of Burgers on Slater St and Imperial Highway. The legendary burger shop has been a fixture in the neighborhood for decades and is its own symbol of defiance and resilience in the face of change.

Owner Cynthia Hawkins tells Tim and I that originally, Interstate 105 was supposed to have an off ramp to Imperial that would have run right over the burger shop. Hawkins’ father and the community fought tooth and nail to keep that from happening. Then in 2016 when CalTrans wanted to sell land that it had leased to Hawkins for decades, the entire community stepped in to stop any disruption to the business. After a little bit of lunch just off Slater, we head to Watts Towers, the iconic tower sculptures that were built over a period of 33 years

The towers are a national landmark and have been the subject of numerous protests and conservation efforts to keep them from being demolished. Now, the park in front of the towers is home to older members of the community, playing dominos and talking about the state of the world as we drive towards a vacant lot.

These examples of resilience and community quickly give way to a call to action as we pull up to Graham Ave, where a lot is fenced off for development. A sign warns against the possibility of chemical exposure in soils at the site. But what the sign curiously omits is what chemicals might be present. Those are the present day battles that Tim and the WLCAC are fighting as development from outside begins to encroach upon the neighborhood. Everything comes back to community advocacy on a micro scale. Members of Watts working to preserve what they have and maintain the culture of what created a community that has survived redlining, a 1965 rebellion, the 1992 riots and now the slow march of gentrification.

It’s a battle for the soul that is happening in the long term and where advocates are needed in a variety of ways. JuJu, intrinsically, seems to know this already.

“My grandpa,” she says, “he has so much knowledge on everything. I still don’t know a lot of it. I’m always constantly learning facts and different things about him and my great grandfather and what they did for the community. But I just think there’s always things to learn and I think it’s a conversation that’s always going to be there for me to continue.”

“The unique thing is that the same passion [JuJu] has for that has continued to be authentic and real,” her head coach, Lindsay Gottlieb, adds. “She can impact the community in different ways. She does her ‘Good JuJu Give Backs’. I think she understands when and where and how she can show up for people and they show up for her. It’s all kind of evolved, I think, very organically.”

As Tim, very generously, drives and drops me off at Los Angeles International Airport, everything clicks into place. The evolution of struggle, of defiance, of resilience, response, patience and advocacy of Watts all exists within the body and mind of one of its’ brightest young stars. A person with the world at her fingertips, an understanding that it can be done on her time and the blessing of her family, some of Watts’ greatest activists and advocates, behind her. She learns, she listens, and finds ways to positively impact the world she resides in. While societal pressures might ask or demand of her to speak on anything and everything, even at an age where there is so much learning still to do, those in her circle want her to grow into the role she chooses and know that they are with her every step of the way.

“I have to be critically careful because I don’t want to be perceived as someone that objects to anyone else enjoying how they manifest their idea of success,” Tim says as we wrap up our discussion. “Along with that, goes my granddaughter. This whole conversation has been about this moment. That she deserves the right to enjoy her life the way she chooses.”

absolutely tremendous story, Andrew. i loved it!

Tremendous. Thank you.