The Legendarium: A Gold Mine on The Beach

While USC and UCLA get the credit for building women's basketball in California, another program laid the foundation for the fast-paced, high scoring game taking over the game today.

The legend is that the walls of the Gold Mine would sweat. Ask Long Beach State players and they’d say the energy would quite literally seep through the pores of the concrete walls. A capacity crowd would never exceed 2,500 people but it always felt like more. Penny Toler would have to tell fans to step back so she could inbound the ball. The hardwood would shake and rumble, especially when USC or UCLA came to town. Cindy Brown can see it all in her head, years later. The crowd, the gym, her Long Beach teammates and head coach Joan Bonvicini, frozen in time as their younger selves.

They were legends of the LBC. Pioneers of pace. While the history of women’s basketball out west is typically traced through USC, the reality is that down the 710 there was another program that played a modern game. ‘Showtime’ draped in black and gold. Playing in a Gold Mine on The Beach.

"Iowa by the Sea”

About three miles from the campus of Cal State-Long Beach is Belmont Pier and the waters of the Pacific Ocean. The outside observer may think of the city as an outpost of Los Angeles, where surfers with bleach blonde hair congregate and spend their days basking in the southern California sun.

The reality is quite different.

“Some of the first big immigration waves were farmers from Iowa and the rest of the Midwest,” explains sportswriter Mike Guardabascio, a Long Beach resident and historian of the area. “The nickname here early in the 20th century was ‘Iowa By The Sea’.”

In the shadow of Los Angeles’ glamor and showmanship, Long Beach rapidly became the industrial engine of the region. Fueled by a mass migration of Midwesterners, the city began to expand significantly. In 1886, the first ever ‘Iowa Picnic’ was held halfway between Pasadena and Los Angeles. Eventually, the event set up shop in Long Beach where it became one of the largest regional annual gatherings. Within that culture, girl’s basketball began to take root.

“Those farmers — while you wouldn’t say they were super progressive on a ton of issues — their expectation and lifestyle was that their daughters work on the farm,” Guardabascio says. “The idea that ‘my boys get it and my girls don’t’ didn’t make sense to them.”

As if they were running along parallel tracks, Long Beach and Iowa simultaneously began to cultivate their own culture of women’s hoops. In 1907, with a round of ice cream supposedly on the line, the Long Beach Poly High School girls basketball team defeated the boys 20-14 en route to winning the first of three straight Southern California Girls Basketball championships.

“They were playing against Cal and USC because there weren’t enough high school teams to play against,” adds Guardabascio.

Poly didn’t just play the college teams, they beat them. But prevailing attitudes at the time were that girls had no place in sports and, in 1908, the Amateur Athletic Union — AAU for short — took the position that women couldn’t play basketball in public places. Six years later, the American Olympic Committee openly opposed the inclusion of women in Olympic competition.

For a period of time, that early culture of girls basketball was lost in Long Beach. Agriculture and farming culture gave way to more industrial jobs as oil was found in Signal Hill and other areas. Soon, the Long Beach Oil Field was supplying one fifth of American petroleum consumption and by World War II, the city had become a manufacturing hub and sending off point for much of the material might that defeated the Axis powers.

But by the 1960’s, social change was happening in America. The women’s rights movement started to gain steam and girls participation in sports began to spike again. In 1962, Frances Schaafsma arrived at Long Beach State to coach basketball and volleyball. Tapping into a long forgotten culture of women’s hoops in the area, she managed to win 11 straight conference titles from 1965-1976.

One year later, Schaafsma was looking for a new assistant coach. Over at Cal Poly Pomona, under the tutelage of the legendary Darlene May, a hungry 23 year old was ready to make a step up in the coaching world.

‘Joan The Recruiter’

Joan Bonvicini knew the way to build a program was to be a saleswoman. By the late 1970’s, governance of women’s basketball was still under the control of the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, or AIAW, and recruiting rules, while strict, weren’t always enforced.

Top players from all over the country were starting to see the same type of attention as their male counterparts. And sometimes, a coach had to go above and beyond to get a foundational piece to take their program to the next level.

Which is how Joan Bonvicini found herself on a late night flight to Indiana in 1978.

“I go into my athletic director [Perry Moore],” Joan remembers. “I'm an assistant coach and I tell him, ‘I need to fly to Chicago to see this kid LaTaunya Pollard’. And he goes, ‘No’. And I said —even now I can't believe I said this — I told him, ‘this will be the best player to ever play here’. And he goes ‘Joan, you already lost her’. I said, ‘ I know I'll get her if I go. It's your fault if I don't get her.’”

But what made the 5’11 guard so valuable? Pollard wasn’t even necessarily interested in playing at the next level. Behind her parent’s home in East Chicago, Indiana, she would dribble and shoot, over and over. That’s where basketball felt its’ most pure and the idea of going off to college didn’t really resonate, despite the dozens of letters and multiple phone calls from interested schools.

“My high school coach, she was like ‘okay, LaTaunya here's the deal. Go to one of these schools and if you don't like it, you can quit’,” she remembers with a laugh. “So boom, it set off a light bulb like okay, I'm gonna go and I'm gonna quit!”

It wasn’t a lack of desire Pollard had but a fear of leaving home and playing at the next level. Once she got past that, every school was ready to offer her whatever she wanted in exchange for a signed national letter of intent. Despite a verbal commitment to Bonvicini and Long Beach State, UNLV thought they could pull Pollard away.

“Las Vegas offered us everything,” she jokes. “Like ‘don’t worry about your grades, we’ll get you set up in apartment, we’ll get you a car’. We were sold. We were supposed to go to Long Beach State and we never made it.”

Joan knew something was amiss. She had asked Pollard to call her after the UNLV visit and never heard back. So, with Moore’s begrudging blessing, she boarded a flight that would get her to East Chicago, Indiana. As she sat in her seat waiting for takeoff she was recognized by one of the passengers on the flight.

“I saw this lady,” explains LaTaunya. “I was like ‘wait a minute. That’s that coach from Long Beach State’. So Joan knew something. She knew she had to be on that flight.”

Joan’s effort made all the difference. When national signing day came, she wouldn’t be blaming Moore for losing the best guard in the country. LaTaunya Pollard’s letter came in, signed and delivered, to the LBSU offices.

Long Beach had their star and a new era was about to begin.

Showtime Arrives in Long Beach

Los Angeles had the Showtime Lakers. In Long Beach, they had the Showtime Niners. Inside the Gold Mine — a small gym that sat, at most, 2500 people — Bonvicini’s team were the original gurus of go.

“I always was a fast break coach,” she says. “But then I put in this transition game that a high school coach had and that we tweaked a little bit. And we went from averaging, you know, the high 80s to over you know, high 90s.”

The success was almost immediate.

From 1979-1982, Long Beach State went 79-19 and 33-3 in West Coast Athletic Association play. While there was not yet a three point line in the women’s game, Pollard established herself as a long range sharpshooter.

“Her first game as a collegiate player, I want to say she had 32 or 33 points and made her first 10 jumpers in a row,” Joan recalls. “I won’t say Caitlin Clark logo but definitely deep threes.”

Pollard finished her first season at Long Beach averaging 19.4 points per game on 51% shooting. She was selected to the 1980 Olympic team but because of the United States boycott of the Soviet Union, she didn’t get the opportunity to play for Team USA. But that loss never got her down. She returned to California and just kept scoring.

“I remember one game in particular that LaTaunya was shooting the ball on the far baseline,” says teammate Roz Boger. “And she stepped out of bounds and made the shot. And the refs looked and was like ‘aw, **** it. Two.’ He gave her the bucket!”

Her legend began to grow as Long Beach started to challenge the two regional powers, 1978 AIAW champion UCLA and budding dynasty USC. While LBSU typically got the best of the Bruins, the Trojans were a different story. With a starting five loaded with talent and headlined by a fabulous freshman named Cheryl Miller, they seemed primed to be the next Immaculata or Delta State.

But on a January night in 1983, they had to come to The Gold Mine. A place where the walls would sweat and LaTaunya Pollard would not miss.

“It was like the fans were right there on the court,” she would say later. “And it was so loud in that gym and just packed. Every time I got the ball, I scored or my teammates were looking for me.”

The prior year, Long Beach had beaten USC in triple overtime and this game felt just as competitive. Four quarters wouldn’t be enough to decide the matchup. With time winding down in the first overtime period, Pollard made magic happen.

“This one play where Cheryl Miller was guarding me up under the basket. I received the ball and I went up for a shot, she went up to block it, I came back down with it, double pumped it and made the shot. The crowd fell out of their seat. It was the best moment in the history of basketball for me.”

Pollard and the team handed the Trojans one of their only two losses that year. But USC would get them back in February and then again in the NCAA Tournament with a trip to the Final Four on the line. LaTaunya won the 1983 Wade Trophy and finished her career as one of the NCAA’s all-time leading scorers at the time. Her senior season, she averaged 29.3 points per game.

Now it fell to the next generation — Roz Boger and those still to come — to do what that first class couldn’t: make a Final Four.

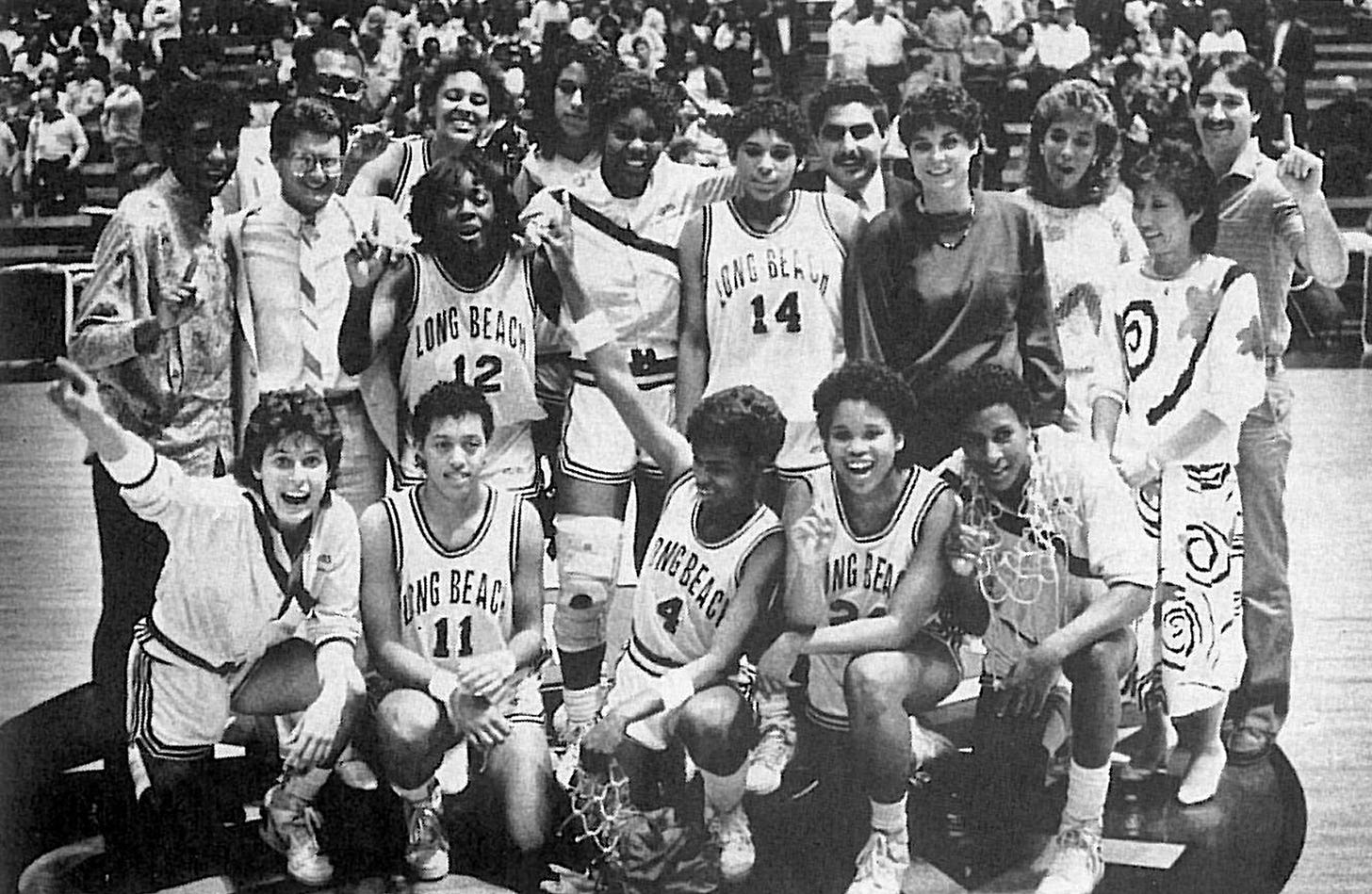

The Ladies of The LBC Make Their Run

It was the largest paying crowd in women’s basketball history at that point. Over 16,000 fans expected in the Erwin Center in Austin, Texas for what was one of the biggest style clashes the sport had ever seen.

Long Beach State vs. Tennessee with Louisiana Tech waiting in the Championship.

This was the pinnacle that Joan Bonvicini’s team had been working towards. In prior years, there had always been someone. In 1983 and 1984 it was USC, who took out LBSU in the Elite Eight. The next year, Long Beach finally got the Trojans in the Sweet 16 only to lose to Georgia one round later. Then in 1986, Louisiana Tech robbed them of a chance to see USC in the Elite Eight again.

Years of heartbreak had finally led them to the promised land but when they got there, it was clear they would have to play their best.

“It was the first experience where I saw real post players,” says Cindy Brown. “And I learned, Ms. Brown ain’t no post player!”

She may not have thought she was a post-player but she was an All-American all the same.

Cindy had arrived at Long Beach in 1983, just after LaTaunya Pollard graduated. While her predecessors were focused on building a program up, she was tasked by upperclassmen like Roz Boger and others with maintaining the standard. Her head coach instilled that in them from the very beginning.

“One of Joan’s favorite quotes was ‘take no prisoners. Kill ‘em,’” Brown says with a chuckle.

They were tough, well conditioned and routinely hung 100 or more points on opposing teams. Legend has it that UCLA stopped scheduling Long Beach State after the 1987-1988 season due to a 103-57 beatdown on opening night. But to get to the Final Four, Long Beach State needed a game changing guard.

Enter Penny Toler.

For the first two years of her career, Toler was one of the few that got away from Joan Bonvicini. It was a recruitment with a couple different twists and turns that started with a verbal commitment to Long Beach and ended with Toler signing with San Diego State.

After one Sweet 16 trip, things changed down south. Aztecs star Tina Hutchinson was sidelined by injuries and Toler felt she needed a change of pace. So she sat out a year and was re-recruited by schools all over the country. But there was only one destination in mind.

“[Long Beach State] needed a guard and I needed a good team and a good coach to play for,” she says.

Toler didn’t realize it at the time but she would also need a second family. One that could wrap their arms around her in her hardest moments.

“I had just lost my parents,” she explains. “My father had just died and my mother passed just five weeks later. So for me Long Beach was the city that I needed to surround me in my time of weakness when my whole world was shattered. I needed that comfort and I needed that support.”

In Joan Bonvicini, assistant coach Greg McDonald — who Toler still affectionately refers to as a second Dad — her teammates like Cindy Brown and others in the community, Penny became the best version of herself on and off the floor. By 1987, she set a school record for single-season assists and was averaging 21.9 points per game, leading Long Beach to an NCAA record 15 games with at least 100 points scored. The only wish Cindy Brown had was that Penny had arrived on campus sooner.

“If we had Penny for four years, we probably would’ve had four years of championships,” she says.

But despite a 33-2 record and one of the best offenses in college basketball, Long Beach ran into another team of destiny: the Tennessee Lady Volunteers. Led by Brigette Gordon and a young guard named Holly Warlick, Pat Summitt’s team won by 10 and eventually took home their first ever national title.

Cindy Brown finished her collegiate career and Toler remained to help take Long Beach to another Final Four. But in 1988, they were stopped by another SEC team: the Auburn Tigers. In 1989, Toler’s last season with the team, LBSU fell to Tennessee again , this time in the Elite Eight.

Joan Bonvicini could see the writing on the wall. It was just a matter of when the final hammer would drop.

A Change on the Coast

It wasn’t since Cheryl Miller that a high school girls basketball player captured the imagination of the west coast the way Lisa Leslie did. Before she even started high school at Morningside in Inglewood, programs like Tennessee and Stanford were actively recruiting her.

“She always played in the Summer League for the Say No Classic,” says former USC guard Rhonda Windham, who would go on to become the first General Manager of the Los Angeles Sparks. “And I would have a draft. And I remember one guy traded basically his whole team so he could draft Lisa Leslie in the summer league.”

Her talent was borderline mythical in southern California and Joan Bonvicini knew that the key to Long Beach State’s long term survival was securing Leslie’s signature. At the time, the gap between power conferences and mid-majors was widening. Long Beach was finding it hard to recruit against the likes of UCLA and USC, once former competitors in the PCAA but now with a significant advantage in the Pac-10. But Joan still had a shot to pull off one of the greatest recruiting heists in college sports history.

“She committed to Long Beach on a Sunday,” Joan remembers. “On Tuesday, things changed. And she went to USC.”

Neither USC head coach Marianne Stanley nor Bonvicini will ever get into the full details of how it happened.

“I offered her a great opportunity,” says Stanley. “And I offered a job to her coach.”

Joan had also offered Frank Scott, Leslie’s coach at Morningside, an assistant coach position at Long Beach State. What else was offered is lost to history, a set of secrets held tightly by the coaches and players involved. But one thing is certain: once Lisa Leslie left for USC, Joan Bonvicini knew her time at Long Beach was done.

“It was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” she says.

A Long Legacy on The Beach

Bonvicini would go on to the University of Arizona to help the Wildcats find their footing in the Pac-10. One of her top recruits from that era, Adia Barnes, continues to guide the program today as head coach.

Penny Toler went on to score the first basket in WNBA history and eventually become one of the best General Managers in the league, drafting Candace Parker and winning three league titles with the Los Angeles Sparks.

The legacy of Long Beach State is multifaceted, from their pace of play to their star power to the contributions their players made on the game after their careers on the court were done. They were one of the first majority Black teams in the sport to contend at a national level and still dot the Division I record books as one of, if not the most, prolific offenses the game has ever seen.

“We kind of opened the door, paved the way for the next level,” says LaTaunya Pollard, all these years later. “Like Cheryl Miller said, recognize the group of women that came before you but you ask me, I’d say we’re better than everybody!”

“We just set heights, boundaries and records for records to be broken,” Cindy Brown adds. “I hope [modern players] recognize that we never gave up.”

Ask any Long Beach player and they believe that their pace of play and style would fit neatly into the modern game.

“We were a team ahead of our time,” Penny Toler says. “If anybody were to go back and look at our tapes and our style of play, it wouldn’t be any different than what they’re doing right now.”

Between the years of 1977 and 1991, Long Beach State scored over 100 points in 60 different games. Cindy Brown’s 60 points in a game was an NCAA record that stood until 2022.

It’s because of that success that Roz Boger, Penny Toler and others are still recognized within the city. That basketball culture, built by Midwestern farmers and Long Beach Poly students, persisted in those women who broke barriers and, for a time, made the LBC an important piece of the sports’ history in the 1980’s. And while they have been honored by the university at various points, Boger would ask one thing of the administration: to help Cindy Brown finally get her degree.

As the women’s game continues to modernize, you can see echoes of Long Beach everywhere. LaTaunya Pollard’s play style lives on in Caitlin Clark. A’ja Wilson’s versatility is built on dynamic forwards like Cindy Brown. You quite literally cannot tell the story of the modern WNBA without Penny Toler. All three, as well as Joan Bonvicini, Roz Boger, Dana Wilkerson, Kirsten Cummings and more, are part of a program that left in an indelible mark on the game. Playing, once upon a time, where the walls would sweat. In a Gold Mine on The Beach.

"Toler remained to help take Long Beach to another Final Four. But in 1988, they were stopped by another SEC team: the Auburn Tigers."

I'm surprised the team they beat to make the Final Four in 1988 wasn't mentioned. It would have been a perfect tie to the beginning. That team was the Iowa Hawkeyes.