The Legendarium: A Shot on the Hilltop

Before Charlotte Smith's 1994 NCAA Championship buzzer beater, Western Kentucky's Lillie Mason was responsible for the first iteration of 'The Shot' in women's basketball history.

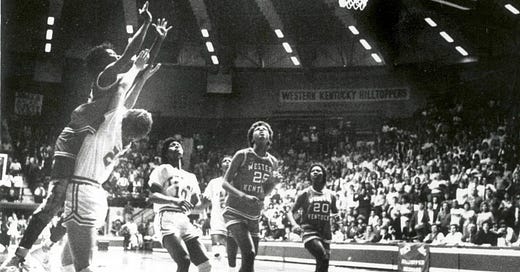

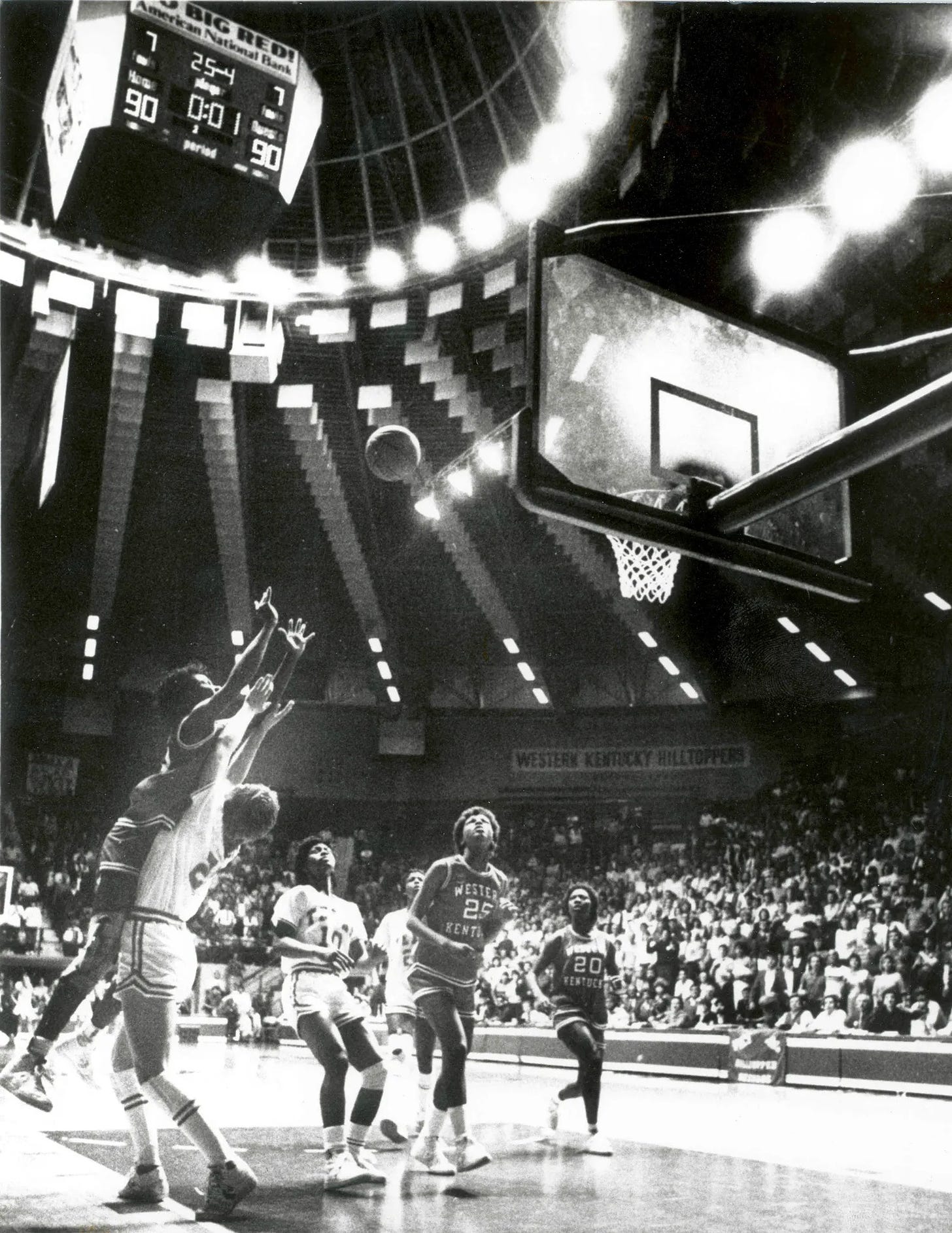

For a brief moment in 1985, time stopped in Bowling Green, Kentucky. Inside the walls of E.A. Diddle Arena, nothing moved except for a basketball. All eyes were transfixed on its’ path, rising towards the hoop and away from Lillie Mason’s hand. One second felt like an eternity. The buzzer sounded, the ball dropped and Western Kentucky’s players felt their senses return.

Lillie Mason, a local kid from Russellville, had hit the biggest shot in women’s basketball history.

Undefeated Texas was undefeated no more. Bested by a bunch of Kentucky kids who stayed at home and became legends on a hilltop.

Bluegrass and Basketball

What many might not know is that one of the spiritual birthplaces of college basketball in Kentucky isn’t rooted in Lexington or Louisville, but a small town on the banks of the Barren River. There, on a hilltop just down the road from Henry Hardin Cherry Hall, the legend of the red towel was born. Edgar Diddle was a basketball coach at Greenville High School when his team played in a tournament in Bowling Green. Western Kentucky officials were in attendance and so impressed with him that they offered the opportunity to be the schools’ athletic director and head coach of all sports. While he started as a head coach of the football, baseball, women’s and men’s basketball teams, he found his passion lied with the latter group. Sporting a hand towel that he had with him at all times, Diddle built Hilltopper men’s hoops into a powerhouse that lasted from 1931 until 1964 when he retired. In his honor, Western Kentucky’s logo became a hand waving that red towel.

By the time Diddle finished his career in Bowling Green, other powers had arisen in the state. Adolph Rupp had taken the University of Kentucky Wildcats and turned them into one of the sports first ‘Blue Bloods’. As Rupp finished his career, Louisville Cardinals head coach Denny Crum was becoming known as ‘Mr. March’. For over six decades, basketball fever gripped the Bluegrass State from end to end.

“I think a lot of it stems from it [being] a very rural and not a very wealthy state,” says Rex Chapman, who was born in Bowling Green. “I think a lot of people that work nine to five or longer, they come home, they get with the friends, put on the ‘Cats and that’s their enjoyment.”

But in this statewide fervor, women’s basketball was largely an afterthought. From 1932 until 1974, the sport was banned at the high school and collegiate levels. Programs like Kentucky, Western Kentucky and Louisville ceased to exist until State Senator Nicholas Baker decided to push a bill through the legislature. ‘Baker’s Bill’, as it would later be called, required that all schools must have a team for the girls if they had a team for the boys. All three major universities were on equal footing in terms of starting their programs again and, rather quickly, the floodgates opened.

“Kentucky is a basketball state anyway and people love to watch basketball, whether it was girls or boys,” Kami Thomas, who was Kami Howard back then, explains. “The boys always drew more attention and had more fan support in high school.”

Like most girls of the era, Lillie Mason grew up playing with her brothers and family members. The youngest of eight, she’d usually be picked last and not want to play on the dirt courts of Hampton Park. But, urged on by her siblings, she learned how to hold the ball, to carry it and to shoot. For hours, she’d watch her brothers and sisters on the court and then would go to their games at school.

“I watched a lot and paid careful attention to my brothers and sisters and go to the basketball games,” she says. “I was very competitive once I really learned what I was doing. I hated losing.”

Soon, she herself would be one of the best players in the state. But it was sometimes difficult for the top athletes to distinguish themselves. Since women’s basketball was technically less than a decade old in Kentucky, the level of competition was uneven from school to school and even within individual teams. But the energy fans brought to the games was still high. It was bluegrass basketball, at the end of the day.

Chapman saw both sides of the sport growing up. His father, Wayne, had played college basketball at Western Kentucky with a man named Clem Haskins. After graduating, they went into coaching; Wayne to Kentucky Wesleyan, where he won two NCAA Division II National Titles, and Clem to their alma mater. By his senior year of high school, Rex was Mr. Basketball of Kentucky, a McDonald’s All-American and Gatorade Player of the Year. He could dominate anyone in the state on the hardwood. But, among all of the men he easily beat on the court, there was someone that beat him handily from childhood until Rex was a teenager: Clem’s eldest daughter.

“Clemette was a target for me my whole childhood,” he remembers. “I couldn't beat her until, I want to say, I was probably 15 or 16.”

“He had mad skills but he was small,” Clemette remembers with a chuckle. “So I was still kind of able to take him until he grew several inches over a summer. And he dunked over my head once when we were playing one on one and I said ‘you know…this is a good time to to bow out!”

While the talent levels in Kentucky girls high school basketball varied greatly, the top players were still some of the best in the nation. But without a regional powerhouse, their playing options at the next level weren’t so cut and dried. Tennessee was an option, as was USC or Old Dominion. Western Kentucky’s Eileen Caty pulled off the first recruiting coup of the era by signing Lillie who just wanted to be somewhere close to home.

“One of my reasons for choosing Western was staying close to home so family could come and see me play,” says Lillie. “And to always get back home when you needed to for a good meal.”

Kami followed a couple years later. But early on in their careers, Caty left and Paul Sanderford became the new head coach at Western Kentucky.

And that’s where things took off.

Climbing to the Hilltop

Paul Sanderford had a mission: make girls basketball cool in the state of Kentucky. In order to do that, he was going to need one of the coolest players in the state to stay in Bowling Green.

“I went to visit USC in California,” Clemette recalls. “I thought, ‘I'm going to go out and visit’ but certainly [I noticed] the palm trees. And [USC guard] Rhonda [Windham] was my host and she really treated me well. It became a really difficult decision.”

It would be tough but one thing that Sanderford knew was that he could lean on two things: the allure of home and the concept of building a program instead of walking into a ready made powerhouse.

“The hype that I tried to give the school and the program was ‘we're going to build something that the fans can be proud of and we're going to do it with local talent and hometown top talent,” says Sanderford now.

When he took over the program, his first phone call was to Lillie Mason to make sure she stayed with the team. Luckily for him, the 6’2 phenom from Russellville had no plans of leaving.

“I never considered leaving because, like I said, close to home and we had players that came in and could play and be very competitive,” she explains. “And, I had played against a lot of the girls on the team in high school competitions during the season. So a lot of the girls were on the team were from surrounding areas, around here in Kentucky.”

It was something that was a little more typical of the times but still unique among the top programs in the sport. Programs like USC, Tennessee and Long Beach State recruited nationally while Louisiana Tech, Cheyney State and Old Dominion pulled players regionally. Even Texas, whose roster was comprised primarily of in-state products dipped into Idaho to get future Kodak All-American Andrea Lloyd.

Sanderford’s intentions were to win but also to make a statement to the people of the state of Kentucky: that women could play basketball and that it be ‘socially acceptable’, as he describes, to do so.

So Clemette Haskins toiled and struggled, wrestling with a choice of joining one of the pre-eminent dynasties of the 1980’s — a program that possessed arguably the most loaded collegiate roster of all-time — or build something new that could live in the annals of Kentucky history forever.

“I wanted to create something,” she says. “I wanted to be part of something on the way up, versus something established.”

Her choice, to spurn USC for Western Kentucky, is one of the most decisive recruiting decisions of the era. And when Lillie made a basket in 1985, Haskins knew she had made the right choice.

‘The Shot’

Lillie Mason, Clemette Haskins and Kami Thomas had played in big games but nothing like this. Even Paul Sanderford was treading in unfamiliar territory. The score was 90-90. There were two seconds left. They had the ball and the chance to beat an undefeated Texas team to advance to the Elite Eight for the first time in program history.

If all that pressure wasn’t enough, Western Kentucky was playing at home in front of 11,000 fans in E.A. Diddle Arena. With the tin roof shaking and the tension rising to a fever pitch, Sanderford drew up a play.

“We had a play that we had worked on,” he recalls. “ It was an ISO in the post as kind of a misdirection where you run somebody off the screen and basically try to relieve the pressure on Lillie Mason.”

Kami would be the one to inbound the ball.

“He's like, ‘Clemette, you run the decoy to the corner, and Lillie, you pop up to the wing. Kami, you just lob it in there. And Lillie, you do your thing.’”

Clemette would draw the defense away.

“I was supposed to come on the baseline for a shot or to create that triangle. But instead I went to the top of the key. And I think some folks came with me thinking that I was going to take the shot. This is before the three pointer, and Kami made the best pass of all. I mean, the hardest part is being the person passing the ball in. So she looks me off and throws the ball into Lillie.”

Lillie would have to be the one to make history.

“I told Kami, ‘just throw it up here. I don't care where you throw it. I’m gonna get it. I’m gonna get the ball. Just throw it. And sure enough, she threw it up there, and it was like slow motion, the ball coming in.”

Lillie caught it, turned and let the ball go with the hope of banking it off the backboard and into the hoop for the game winner. The ball left her hand and her sense of sound went with it.

“I don't even remember hearing the crowd until after the ball went in, and then everybody just started jumping up.”

‘The Shot’ was good. Western Kentucky had defeated the top seed in the NCAA Tournament, undefeated Texas in one of the biggest upsets in the history of the game up to that point.

None of the players went into detail about exactly what they did in Bowling Green that night to celebrate. But everyone says they knew that everything changed after that moment. Sanderford’s goal of making women’s basketball cool in southern Kentucky was starting to come to fruition.

Dear Old Western’s Day

The Lady Toppers still had another game to play to get to the Final Four, against Van Chancellor’s Ole Miss team.

“I had to play him on Sunday afternoon in Diddle in front of another full house and a knock down, drag out game,” Sanderford remembers. “He had a heck of a team. To this day — he and I've been buddies for a long time — he says, ‘I’d have won that game anywhere in the country other than that arena. Other than Bowling Green.”

With the win in hand, Western became the first team ever in the state of Kentucky to make a NCAA Women’s Final Four. Ironically, they ended up in somewhat hostile territory: Austin, Texas. Home of the Longhorns, who the Toppers upset in dramatic fashion one week prior. There, they ran up on another SEC program: Andy Landers’ Georgia team led by Teresa Edwards and a sophomore phenom named Katrina McClain.

The Bulldogs won 91-78, avenging an overtime loss in Diddle earlier in the year.

But Western Kentucky wouldn’t be a one trip wonder. The next season, the state’s basketball fever had infected the women’s game. The tin roof at Diddle Arena was regularly shaking and players like Kami Thomas were recognized everywhere on campus.

“Anybody we ran into, they would always have to say something positive to us,” she says. “[Telling us] encouraging words as we walk to practice or get ready for a game.”

“Now, there's an expectation,” adds Clemette.”It's a beautiful thing. The fans get excited but now they get a taste of it and now the expectation is, ‘oh, well of course they'll be in the Final Four’. But [with] season tickets selling, every home game plentiful with people…It felt like we have arrived and this is the beginning of of the foundation to come.”

During the 1985-1986 season, Western entered the NCAA Tournament 29-3, ranked No. 5 in the country with the Kodak All-American triumvirate of Thomas, Haskins and Mason. The uniqueness of their program — a team filled with local kids that fans knew from their high school days — was now a key piece of their success.

“Everybody knew each other because you saw everybody growing up and watching them, you know?” says Mason. “So it was a close, close knit thing.”

For three rounds of the Tournament, the Western Kentucky kids rolled over their competition. They topped St. Joseph’s at home, dominated James Madison and then blew out Rutgers at The Palestra. Then came a trip to Lexington, Kentucky: the veritable cathedral of men’s basketball in the state. Waiting for them was a ghost of the past.

Once again undefeated Texas with an added weapon: Clarissa Davis, the best freshman in America.

There would be no legendary shot this time. The Longhorns beat Western Kentucky 90-65 before defeating to USC 97-81 to claim the first undefeated National Championship season in women’s basketball history.

“They had something to prove [following the upset] and they proved it in a big time way by steamrolling everyone who stood in their way,” says legendary Texas head coach Jody Conradt.

Lillie would graduate later that year as a three-time All-American finishing her career as the program’s all-time scoring leader, among numerous other records. In the successive years, Thomas and Haskins would finish their time at Western as well. But Sanderford remained, as Diddle Arena continued to fill up for women’s basketball, and added to the foundation built by those that came before.

Tin Roof, Glass Ceiling

The Lady Toppers had one more run left in them. With Kim Pehlke leading the team, Western made an NCAA Championship run in the 1991-1992 season where they fell to a new budding dynasty: Tara Vanderveer’s Stanford.

In 1997, Sanderford’s run in Bowling Green came to an end and he took a head coaching job at the University of Nebraska. Conference realignment had cut the legs out from Western’s ability to field consistently competitive teams and the rise of Louisville and other southeastern programs had dug into the singularly hometown allure that WKU once held. But over the years, they’ve remained a consistently competitive program, regularly making either the NCAA Tournament or WNIT.

While Ms. Kentucky Basketball, the annual award given to the top high school player in the state, still typically attends an in-state program, Sanderford and his former stars aren’t sure if what they built could be replicated in today’s world.

“I don't think it can happen again,” says Clemette. “And I do think that that's what makes our [run] special.”

“That was just something special that we had that nobody else had,” Kami adds. “I think it's pretty neat.”

“I wouldn’t change anything,” Lillie finishes. “Well, maybe one thing. I probably would’ve slam dunked!”

While all three had the ability to play professionally, there was no WNBA yet. As he watched his friend wrap her career in college basketball, Rex Chapman wishes there had been opportunities like what he had: a chance to continue playing basketball and keep the stories of a program like Western alive in different ways.

“I always felt bad that Clemette really didn't have [professional playing] options after Western,” he says. “I was like, this f*****g sucks. She'd be a ‘Dr. J’ of women's basketball right now if there was a pro league here and I felt bad about that.”

But Haskins has found plenty of success in her professional life as has Mason, Thomas, Sanderford, Pehlke and others that came through the program. Their contributions to the game contain multitudes; as a gamechanger at the national level and within Kentucky itself.

“We were a team that captured the imagination of our community,” Clemette concludes. “And our community and fans were as much a part of our team's success as what we were doing on the floor.”

Her only wish for those learning the game today: that Lillie Mason get more shine.

“I believe she could play today,” she says.

But even now, almost 40 years later, ‘The Shot’ still lives in the lore of Kentucky legend. Those that were in the Diddle Arena that day can still see it. The fans, the coaches, the players. Stuck in time for a brief moment on a hilltop in Bowling Green.

“It's the thing that ‘if you build it, they'll come’ and that's what we proved,” says Sanderford, who is retired and back in Bowling Green now. “We proved that was true and so did Ruston, Louisiana, and Old Dominion and Long Beach State. I think the big thing is that that we gained respect for women's basketball and women's athletics and how we ran the program.”