The Legendarium: A Vision in the Phog

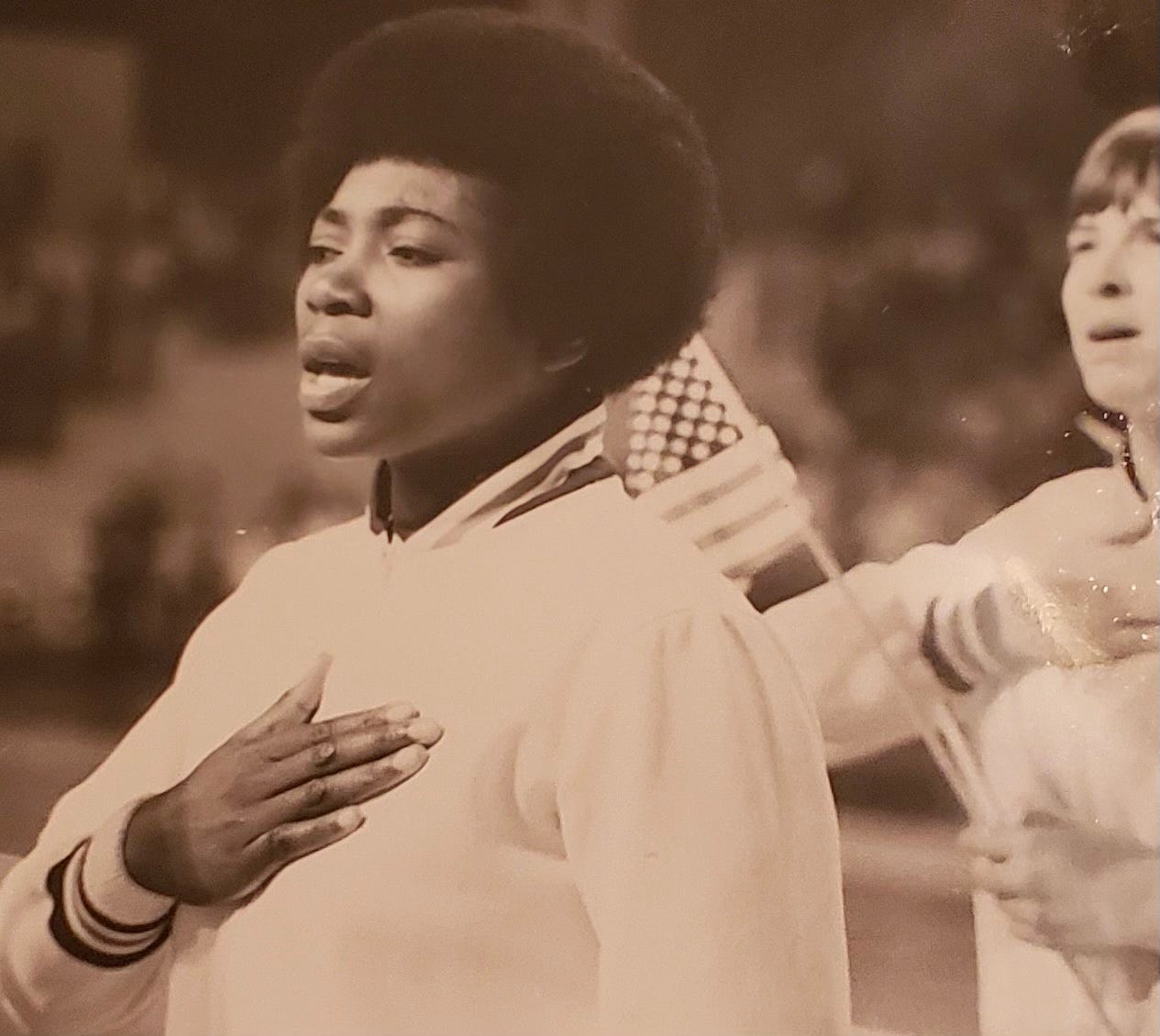

A special Legendarium for Black History Month centers one of the first ever pioneers of the game: Marian Washington. How her legacy lives on and can be carried into the next evolution of the game.

Marian Washington could see it. She knew it. There was no question about it. No gray areas.

The vision was spiritual in nature but she wouldn’t dismiss it. In some ways, it felt like divine providence. After all, how else could she explain her path? One that began in Pennsylvania, took her as far away as Brazil and dropped her in Lawrence, Kansas? It was in her heart and mind. It had to be. A calling brought her to this place to make history and, more importantly, to make a difference.

It wouldn’t be easy but then again, nothing in her life up to that point had been. She had become adept at overcoming adversity, steeling her resolve, looking in the face of a harsh world and fearlessly staring it in the eye. It’s why now, decades later, she can look back at her career and understand her place in history.

To be the first black woman to open a particular door for the many that would come in the years after.

A Small Town in Pennsylvania

West Chester, Pennsylvania looks a lot different in 2025 than it did in the 1950’s and 60’s. Where Market Street now has the look and feel of a college town’s main stretch, Marian Washington grew up during a time when the community was decidedly more rural. Narrow streets were lined with shops owned by black men and women in the community. Her father, Joseph, who also went by ‘Goldie’, owned a do-it-all type of business. Mowing lawns, cleaning schools, fixing cars, he did a bit of everything. But it wasn’t always the easiest life. For the first 12 years of her youth, she and her three siblings shared a mattress in the converted coach bus that they lived in, growing food in the garden outside next to Bolmar street.

It was during those formative years that Marian learned how to maintain strength and determination in the face of unimaginable odds. At the age of 13, she was sexually assaulted and became pregnant which led to her school telling her she couldn’t finish the ninth grade. Later that year, she gave birth to her daughter Marian Josephine (nicknamed Josie) and repeated the ninth grade at a different school. It was there she met a teacher named Ruth Redding who helped her find purpose and direction after an agonizingly difficult 12 months.

By this point in a person’s story, many might fracture, if not break completely. Marian resolved that she was going to do right by her daughter and find a way to make it in the world. As she got older, she began to excel in athletics from basketball to track and field. But this was a period of time in which representation almost didn’t exist at all for women that looked like her. While she could occasionally see tennis star Althea Gibson and sprinters Wilma Rudolph and Wyomia Tyus on television, it was exceedingly difficult to learn about them.

“I went to a library looking for some stories about black females and [Althea Gibson’s] story was the only one,” Washington remembers, “And it was in the children’s section. But it did show me that even though she came up with some challenges, it didn’t stop her. And the ways she found to develop her skills was really encouraging for me.”

Marian continued to excel in both basketball and track, where she became one of the best throwers of shot and discus in the country. As luck would have it, one of the handful of colleges in the region that had a rather progressive attitude towards female athletes in a pre-Title IX was the one in her own backyard: West Chester State. Back then, it was a teacher’s college that brought in many prospective students who wanted to work in physical education.

“I went to West Chester State to play for [Lucille Kyvallos],” says Marian. “But she left.”

Indeed, two shooting stars had effectively passed each other in the sky. Kyvallos left in 1966 to take a faculty position at Queens College in her native New York City, eventually becoming head coach of the women’s basketball team two years later. Washington went to West Chester anyway and ended up under the tutelage of another titan on the level of Kyvallos: a 29 year old woman named Carol Eckman.

“In terms of laying down the foundation,” Marian explains, “Carol Eckman was definitely a name that hopefully we’ll all grow to know.”

Known in the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame as the ‘Mother of National Collegiate Championships’, Eckman helped organize the first intercollegiate women’s basketball tournament in sports history. For decades, the primary national title option for the sport was in AAU, where colleges like Wayland Baptist or Iowa Wesleyan would take on sponsored semi-professional teams like the Raytown Piperettes. Eckman’s 1969 brainchild, the Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (or CIAW), was the seed that became the AIAW Tournament and, eventually, Women’s March Madness.

Washington played in that first title game, in a six player format, alongside 5’2 senior guard Pat Ferguson who led the Rams in scoring. West Chester defeated Western Carolina 65-39 to claim the first national title.

“I knew that Carol had a vision and we were working very hard to help that vision come true,” says Marian.

Soon, Eckman’s vision of equity in sports for women became the vision of Washington and others. After she won that first CIAW championship, Marian was invited to try out for the United States national team. Women’s basketball wasn’t yet an Olympic sport, despite the Soviet Union ardently campaigning for its’ inclusion every cycle since 1958. But the team could still compete internationally in events like the Pan-American Games and the FIBA World Championships. It was at this tryout that Washington crossed paths with another legend: Alberta Lee Cox.

“She exuded confidence and intelligence — strength that you want women to have,” Marian told the Kansas City star in a 2021 interview.

Cox tapped her to play for her AAU team, the Raytown Piperettes, and eventually, Team USA. Whether Marian knew it or not at the time, she was already inspiring those around her including a 15 year old prodigy named Ann Meyers who played in the 1971 AAU Tournament in Council Bluffs, Iowa.

“[Marian] was just so fluid,” Ann explains. “She just seemed bigger. She played bigger.”

What surprised the 15 year old Meyers, at the time, was seeing a fellow player walking around with her daughter in tow. During a time in American society where having children out of wedlock was already frowned upon, if not outright shunned, Marian held her head proudly and kept Josie with her at all times.

“We didn’t see that in women’s athletes,” adds Ann. “You really didn’t see a whole lot of women’s athletes at the time, that had gotten pregnant and had children, came back and played. I just always admired her.” 4”

“I stand in awe of my mother today,” Josie writes in the book Fierce, her mother’s autobiography. “She pushed me to excel at everything I did. And at every step along the way, she was there. Sometimes behind the scenes and other times by my side.”

The Piperettes, behind Washington and a guard named Colleen Bowser, were a force to be reckoned within AAU basketball. So it was only appropriate that when the color barrier broke in USA women’s basketball, it was her and Colleen to do it. There was even a belief at the time that they’d be competing in the Munich Olympics in 1972. The story goes that the Olympic Committee had too many events to add women’s basketball to the summer schedule. Cox allegedly told Marian and her teammates that the IOC forgot.

While that dream ended, another was set to begin. That very same year, the United State congress passed Title IX legislation which opened the door for women’s basketball in a way it had never been opened before. Marian’s vision wasn’t clear yet.

Soon, it would be.

A Vision in a Fieldhouse

When Marian was in high school, she crossed paths with the legendary discus thrower Al Oerter. He had won Olympic gold in 1956, 1960 and 1964 in Tokyo where he famously fought through torn cartilage in his ribs to set a new Olympic standard and take home his third first place finish.

“These are the Olympics. You die for them,” he had allegedly told the doctors.

While working with Marian for a week, he told her to look up his college coach in Lawrence, Kansas if she ever found herself out that way.

“On the east coast,” Marian says now, “Kansas just seemed out of the picture, of course, but so far away.”

How ironic then, that she should find herself in Missouri, less than 100 miles from KU’s campus. She went looking for Oerter’s discus coach, Bob Easton and became a graduate assistant coach while working to earn a master’s degree. But soon she’d be in the office of university chancellor Archie Dykes, speaking in front of committee comprised of board members and athletic director Clyde Walker.

In 1973, she was named the head coach of a brand new women’s track and field team at Kansas. One year later, Marian Washington made history as the first black woman to become the head basketball coach at a major division I university. She didn’t realize the significance at the time, only that there were challenges ahead and battles to be won. Making matters trickier was the obvious: that she was a black woman in the middle of Lawrence, Kansas.

“There would be times where I just didn’t know whether I was facing an obstacle because I was a woman or because I was a black woman, or both,” she recalls. “That went on, really, for much of my career.”

Her biggest battles came with Walker, who was an open opponent of women’s sports and didn’t want to be responsible for them. Like many men in collegiate athletics governance of the time, the widely held belief was that Title IX would take investment away from football and, in the case of Kansas, men’s basketball. Things reached a head when an article in the KU student newspaper quoted Walker and was shared with Washington.

“Ninety percent who contribute to our program could care less about women’s athletics,” he told the paper. “There aren’t any women who can compete with men and they readily admit it.”

Marian shot back with quotes of her own. countering Walker’s contentions openly and asking for evidence of his claims. The two met in his office, resulting in Marian walking out with the belief that her time in Lawrence was done. Instead, Chancellor Dykes decided to split the athletic department, giving Washington sole control over women’s sports and reporting directly to him. She was now the first ever women’s athletic director at the University of Kansas too.

The vision was now clear.

In some ways she had to break down walls and build up others. Sometimes quite literally. It was she who fought (and won) the battle to give her players a locker room in Allen Fieldhouse, negotiated a shoe contract with Nike to free up budget for other sports while fighting for just a universal gym for all women’s athletes.

“There was a culture that had to be changed,” she says. “You had to stand firm in your vision and that you knew women deserved to be respected and have the same opportunities.”

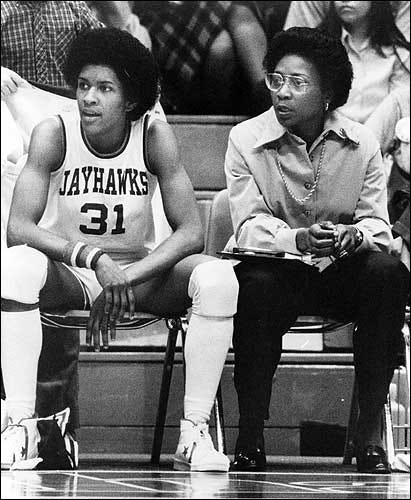

One of the people who noticed that stalwartness was a teenage basketball prodigy from Wichita named Lynette Woodard, even if she didn’t yet understand Marian’s broader importance.

“I grew up playing on the playground,” explains Lynette. “So the news of Title IX, I really didn’t understand any of it. No one really talked about it. I actually didn’t hear that phrase until I got to college.”

Now, growing up on the playground is only a part of Woodard’s story. In 1965, near McConnell Air Force Base just outside of Wichita, a Boeing KC-135 stratotanker crashed in a neighborhood, killing all seven crewmembers on board and 23 people on the ground. Lynette, just five years old at the time, watched from her backyard as neighbor’s houses collapsed.

From the ages of 5-10, the area where the stratotanker crashed was an empty lot until 1970 when it became Piatt Park. That was the playground where Lynette played with her brother Darrell and future superstars like Darnell Valentine, who lived in the same area. Soon, her skills started to attract the attention of major women’s basketball programs, including Marian Washington’s Kansas team. As a freshman in high school, Lynette’s team won the state championship and had her medal placed around her beck by none other than the Jawhawks head coach.

While she wouldn’t see Marian again until later in her high school career, it was a set of press clippings that kept the head coach in Lynette’s mind.

“I did read about her while I was in high school,” she remembers. “She had fired a coach and it had came up in the paper. It was a little, small picture of [Marian] where all you can see is this afro, right? And it just talked about her firing this coach and the coach happened to be white.”

“And I thought to myself at the time — because you know, I don’t know nothing — I said ‘wow, this black lady fired this white lady!’ I’d never seen anything like that,” adds Lynette. “Two years later, I come back and she fired another white lady. And I’m like, ‘if they don’t lynch her this time, this lady must be COLD!’”

Lynette didn’t think much of it after that but it made an impression whether she knew it or not.

“Once I met her, I wanted to play for her,” Lynette says. “She had an afro, which I identified with. But I grew my ‘fro because of Angela Davis.”

As luck would have it, Marian remembered Lynette too. But it was because of Marian’s daughter Josie, who was a senior at Lawrence High School while Woodard was a sophomore. The state 5A tournament was happening in town and Josie saw Lynette and walked straight up to her after a game and told her, “you have to play for my mom”.

Lynette did, and there she and Marian Washington were. Two black women in Lawrence, Kansas who tasked themselves with building a juggernaut of a program in an area that was deeply intertwined with basketball history yet reticent to allow women to share in that experience. In spite of that, they won and won a lot. With Woodard as the leader of the team, the Jayhawks won the Big Eight three straight seasons from 1978-1981 making the AIAW Sectional each year and amassing an overall record of 86-21.

Lynette would go on to set a national women’s basketball career scoring record of 3,649 points before the implementation of the three point line. She held records in points, rebounds, assists and steals at KU for years. In 1981, they were ranked No. 3 in the nation, the highest in program history. But Kansas got a tough seed in the AIAW Regional, having to meet UCLA in the round of 16. They lost to the Bruins 73-71 in Lawrence, who went on to lose to eventual champion Louisiana Tech in the quarterfinals. It was a difficult pill to swallow but an unequivocal run of success for Washington and her Jayhawks.

But beneath the joy was pain that Lynette and her teammates weren’t aware of. The team was becoming successful yet Marian was still fighting battle after battle for baseline respect. After one game she tracked down a visiting radio crew, who referred to Jayhawk players as ‘jungle bunnies’ on the broadcast, to give them an earful. Department wide, Kansas got hit with multiple Title IX lawsuits about inequities between men’s and women’s sports.

“I just didn’t know how I was going to get up the next morning, reading maybe some derogatory article or having to work with some people that you know didn’t mean the best for you,” she explains. “It was just not easy every single day but it would not move me.”

The athletic departments at Kansas merged in 1979 and Marian devoted her time fully to women’s basketball as opposed to being an associate A.D. under new athletic Bob Marcum. While the job changed, the vision hadn’t. And now, it was more clear than ever before.

A Long Kansas Road

Lynette Woodard would go on to graduate and become the first ever female member of the Harlem Globetrotters, won gold with Team USA at the 1984 Olympics and managed, at age 36, to play in the inaugural WNBA season. But in Lawrence, her mentor and head coach persisted. Kansas won the Big 8 two more times in 1987 and 1992. By the mid 1990’s they were a consistent competitor in the conference and a regular NCAA Tournament entrant.

In the late 1980’s, Marian fought hard on the recruiting trail for a young point guard out of Philadelphia, even getting the chance to visit the family at their home. She hoped that a local connection would help her win the race but Dawn Staley decided that Virginia was ultimately the right program for her. Four years after that loss on the trail, Washington would again head east to try and sign an elite guard.

“I remember [Marian] coming into the house and everybody just being so impressed with what she was telling us and how she presented herself,” says Tamecka Dixon.

The New Jersey native was a WBCA High School All-American and had nearly every program in the nation recruiting her. UConn, fresh off a 1991 Final Four run and making a beeline to national prominence, was hot on her trail. 30 different coaches visited her home. But it was Coach Washington that stood out.

“She became a part of the family right away,” Dixon recalls. “My grandma was there. She cooked for us. [Assistant] Coach [Renee] Brown and Coach Washington were washing dishes. They just fight right in.”

It helped alleviate any concern about what Tamecka might face in Lawrence, a place that was almost alien to a family from Linden, New Jersey. The connotation of ‘the midwest’, especially in the early 1990’s, was well-known to the Dixon’s.

“I remember her saying, ‘I don’t promise too many things,’” Tamecka says. “But I promise that if Tamecka comes to Kansas, she will be taken care of.”

From 1993-1997, the team won over 20 games ever season while winning the conference twice and making the Sweet 16 once. In 1994, the Jayhawks set a conference attendance record of 13,582 in a 59-57 win against a contending Colorado team. Tamecka was the Big 8 Player of the Year in 1996 and the Big 12 Player of the Year in 1997 before enjoying a long career in the brand new WNBA. During that period, Marian spent the summer of 1996 with Team USA becoming the first black woman coach on an Olympic staff.

One season later, Lynn Pride helped lead Kansas to the Sweet 16, marking the first time in school history the women’s team advanced further than the men. But things started to change significantly after 2000. Out of what seemed like nowhere, the Jayhawks went from 20-10 to 12-17 and then to 5-25, with a stunning 0-16 record in Big 12 play. What most didn’t know was that Washington’s health was deteriorating and she didn’t know why. It would take years for her to discover that she had Lyme Disease and some of the chronic fatigue she dealt with in those final years was related to it going undiagnosed.

In 2004, Marian resigned after amassing 560 career wins at KU, a program record that still stands today. Since her decision to step down, there have only been two coaches at Kansas in the last 20 years: Bonnie Henrickson and Brandon Schneider. For a period, Washington felt as thought opportunities were afford to Henrickson in a way they weren’t to her. The Jayhawks of the 2000’s were allowed to compete in the WNIT if they missed the NCAA Tournament, an allowance made only after Marian had left the program. Henrickson made two Sweet 16’s before Schneider took over in 2015.

While it has at times felt like her legacy has been mischaracterized relative to others at the school — those who ordained themselves as pioneers seemingly at her expense — Washington has remained in the fold in Lawrence. She was invited back to the school by athletic director Travis Goff and the women’s basketball suite at the university now bears her name.

It took a long road to get to a place of reconciliation but Marian, stalwart as ever, knows that healing also lies in one’s own security.

A Retrospective of Greatness

“She had to deal with forgiveness,” says Lynette, chatting over the phone after a book event with her former head coach. “I knew the undercutting that she must have been experiencing with what I had read in the papers and I’m like ‘if I could help this program, if I could help this woman, I’m going to go there.”

It’s that forgiveness that Lynette herself has also had to learn and something she remains in awe of when it comes to Marian Washington. Nowadays, she has a group that she meets with to talk about hang ups and hurdles in life. It’s mostly for support but also to gain clarity to help in healing.

“What I learned from that group was to choose love,” she explains. “When I got that concept and start running it back over my life and the people around me, that’s what she did. She walked in love and she walked in faith.”

To some, it’s almost unfathomable how Coach Washington managed to do it. To go from her upbringing to her motherhood to taking over a major collegiate athletic department before the age of 25 and then fighting decades of battles for the advancement of women, black women in particular. It almost seems impossible to believe that that experience wouldn’t harden someone.

And yet, Marian speaks softly and deliberately over Zoom as she details her legacy and the importance of leaving the door open for others to follow.

“[Basketball] was the vehicle that gave me a chance to impact some young lives,” she mentions. “I don’t think that I would have been able to do that if I had gone a different direction.”

She, along with the likes of C. Vivian Stringer and Edwina Qualls — the first black women’s head coach in Big Ten history, hired in 1976 — were the forerunners that paved the way for the likes of Carolyn Peck and Dawn Staley. Peck was the youngest head coach and first black woman to win an NCAA Tournament while Staley is arguably the best coach in the game right now, having won two of the last three NCAA Championships.

With them is a generation of coaches establishing themselves at the national level — like Niele Ivey at Notre Dame and Yolette McPhee-McCuin at Ole Miss — and behind them a talented group of up-and-comers from UT Arlington’s Shareika Wright to Tulane’s Ashley Langford and Charlotte’s Tomekia Reed.

Tamecka Dixon went on to become a three time WNBA All-Star and two time WNBA champion while was inducted into the Women’s Basketball and Naismith Hall of Fames in 2004 and 2005. And that’s to say nothing of other former Kansas stars from Angela Aycock, Lynn Pride, Angie Hableib, Adrian Mitchell and others.

“She had to create the room,” says Tamecka. “It wasn’t very many before her to give her kind of a blueprint. She was that blueprint.”

“She fought to set the example for everybody who comes after her because they’ll never have to deal with what she dealt with in order for others to receive what they receive,” Lynette adds. “We only focus on the championship coaches. What about the other coaches? There’s a whole sea of people who are teaching and coaching and fighting and striving to help push the next generation forward. She stands as a beacon.”

Marian herself, in characteristically unselfish form, directs the discussion of legacy to players like Lynette and those that were around at the very beginning with her. She emphasizes her West Chester coach Carol Eckman and how she feels that her achievements warrant more discussion before talking about player records in the AIAW. Coaches, she notes, are allowed to keep their wins and losses for NCAA record purposes but player records, like those of Lynette Woodard or Pearl Moore, have been largely erased.

“Don’t let our history be diminished,” she concludes. “We just cannot allow great athletes [to achieve] and not celebrate it and their contribution. We need to keep the past and the present. We need to be proud of our history.”

But what Marian might not realize is the pride her players have in her part of the game’s history and that, all these years later, a vision became a reality and is now being passed on to those who come next.

“She’s a wealth of wisdom and knowledge,” says Lynette, wrapping up our phone call. “You talk to her, you’ll the light and you’ll see a way for your path. She did it all.”

If you’d like to read more about Marian Washington, her autobiography, ‘Fierce’ , co-written by Vicki Friedman, was published in 2024 and is available for purchase at this link.