The Legendarium: Fancy Dancers in Missoula

In a special Legendarium installment for Indigenous People's Day, No Cap Space WBB highlights the pioneering Native women that broke barriers in Montana and brought 'Rez Ball' to the NCAA.

On this Indigenous People’s Day, No Cap Space WBB brings you a special edition of The Legendarium. This story takes us to Montana to highlight the trailblazing women of the Blackfeet Nation and the barriers they broke in Division I women’s basketball. If you’re looking for our weekly column, ‘Five Out’, it will publish on Tuesday.

The Backbone of the World

Old Man came from the south, making the mountains, the prairies, and the forests as he passed along, making the birds and the animals also. He traveled northward making things as he went, putting red paint in the ground here and there—arranging the world as we see it today.

He made the Milk River and crossed it; being tired, he went up on a little hill and lay down to rest. As he lay on his back, stretched out on the grass with arms extended, he marked his figure with stones. You can see those rocks today: they show the shape of his body, legs, arms, and hair. - Chewing Black Bones, 1953

On one end of the borders of the Blackfeet Reservation are the endless expanses of the Great Plains. On the other, the ‘Backbone of the World’ — what we call the Rocky Mountain Front — and Chief Mountain, or Nínaiistáko, which will crumble when the end-of-days arrives. Prairie land and tall grass stretches for miles, setting the earth ablaze with a bright yellow fire. The mountains of the Rockies and Glacier National Park shoot up from the ground, painting the horizon colors of gray rock, white snow and magenta sky. These are the ancestral lands of the Blackfeet which have been dispossessed, shrunk and encroached upon over hundreds of years.

It’s on these lands that Malia Kipp learned to play basketball.

“I do remember being tiny and my dad and his city league team let me try and warm up with them,” she remembers. “My dad lifted me up and [had] me dunk the ball.”

Basketball was embedded within her family but it was hardly out of the ordinary in and around Browning, the central town and main hub for the western side of the ‘Rez’. Everyone Malia knew would play ball, from her Dad to her cousins. If she didn’t learn how to shoot and dribble, she wouldn’t get picked and, being the only girl in the family at that time, she didn’t want to sit on the sidelines by herself.

By the time she entered grade school, the Kipps had gotten a place about 12 miles northeast of Browning. Malia’s father, a carpenter and building inspector, decided to build a treehouse while putting together a shelter belt (also known as a windbreak) and wanted to add something to keep the kids occupied: a basketball hoop on the side of one of the outer walls. Malia would spend plenty of time out there, kicking up dust on the dirt court until the sun would go down.

“They were still trying to grow grass,” she adds. “[And] then we were playing ball out there, so grass wasn't growing.”

Basketball became a go-to for her and others within the community. Part of it was a way to occupy time and part was to stay out of trouble. Years, decades and centuries of marginalization by the United States government had created several issues on reservations like the Blackfeets’. Crime, poverty and alcoholism were common themes while advanced education wasn’t regularly attainable. The difficulties of life came as a result of what had come before, over and over, at the hands of settlers and those who deluded themselves into believing subjugation and termination was an essential part of progress.

For generations prior to white exploration the Blackfeet were semi-nomadic, following the buffalo herds across the Plains and towards the base of the Rocky Mountains. But aggressive colonialization of the American west saw that lifestyle change rapidly and radically. The buffalo, considered caretakers of the land, had been hunted to near extinction in the 19th century, effectively destroying a vital lifeline of food, shelter, clothing and culture for the Blackfeet. In 1855, they signed a treaty with the United States to be given a large swath of land in what is now Montana but over time, those lands were whittled away until 1888, when present-day borders were officially established. Generations of Native men and women have learned and lived with the inflicted trauma of displacement and destruction without many healthy alternatives for recourse. But over that time, there’s been resilience and a preservation of cultural staples.

And there’s also been basketball.

Freedom on the Floor

Basketball’s relationship with the Native community in North America has always been relatively complex. Sports was a vital part of Indian boarding schools’ missions to make tribal children more ‘American’ by way of forced assimilation. But while the ‘normal’ way of playing was typically slow, plodding and based in set formations and plays, teams were caught by surprise with the speed and flow with which the Indian schools played. Carlisle, one of the most well-known boarding schools, excelled at both football and basketball while producing one of the greatest athletes of all-time in Jim Thorpe. The Native way of playing — what is now called ‘rez ball’ — even caught the eye of even the earliest hoops pioneers.

““I made it a point to see several games at Haskell,” James Naismith, the founder of basketball would write, “because I delight in the agility of the Indian boys.”

Haskell, for the unfamiliar, was a boarding school just south of Lawrence, Kansas where the University of Kansas was located and basketball really took off. Even as sports was being utilized as a tool to phase out tribal culture with white American creations, young boys and girls were finding a way to reclaim their culture and self expression on the hardwood. Without professional teams or even collegiate athletic programs located on reservations all over the country, local high schools became the centerpieces of sporting culture. And thus, rez ball became a source of pride and importance within tribal communities.

“It [was] freedom and self expression,” says Simmaron Schildt, a member of the Blackfeet nation who was younger than Malia. “I was really quiet in high school and college. One of the only times I felt like I could let all of that go was when I stepped onto that court.”

The game was fast, unscripted and predicated on deceptive defense and running in transition.

“[It was] getting people to think that, ‘oh, I’m going this way’ and then because I want you to throw that way, you’re waiting for them to do so,” Kipp describes. “It was free. It made us feel good.”

In Browning, the tradition was taken a step further. For girls and boys basketball games, the entire community would come out. Malia remembers tribal elders, including the legendary Blackfeet leader Earl Old Person, taking seats towards the top of the bleachers to watch them play. The team would run out to traditional tribal songs, run the floor and win basketball games.

“It was giving people a reason to speak well about Browning,” says Schildt, who would lead the team to a 1996 Montana state title, their first ever, “because all you ever heard in the news was tragedy.”

Fleet of foot, with an unparalleled mental resilience, players like Kipp and Schildt built Browning into a girls basketball program that competed the way the boys team did. But, like it was for many on the Rez at that time, the idea of playing major college sports was a lofty goal, if not completely unattainable. That is, until Malia got a call from Robin Selvig at the University of Montana.

Robin & The Rez

By the early 1990’s, Robin Selvig’s Montana Lady Griz were one of the best shows in the state. Throughout most of the 1980’s, UM was winning the Big Sky Conference nearly every year, heading to NCAA Tournaments and occasionally upsetting a higher seed as they did in the 1986, 1988 and 1989 seasons.

“I was blessed to be at a place [where] they really, once they paid attention to how good women could be, started becoming great fans,” Selvig says. “For the size of the state, it had very good high school basketball and I was able to get a lot of D1 players out of Montana. That was the bedrock of our program.”

But for over a decade, he hadn’t recruited any Natives to his team. There had been players from reservations that had played Division I basketball on the men’s side and even at the University of Montana but Malia Kipp stood to make history in 1992.

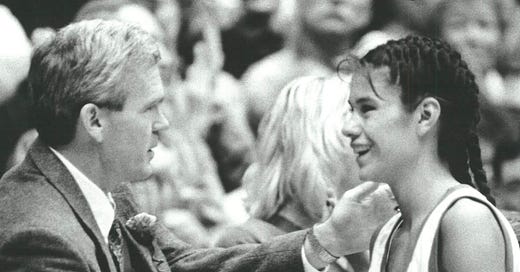

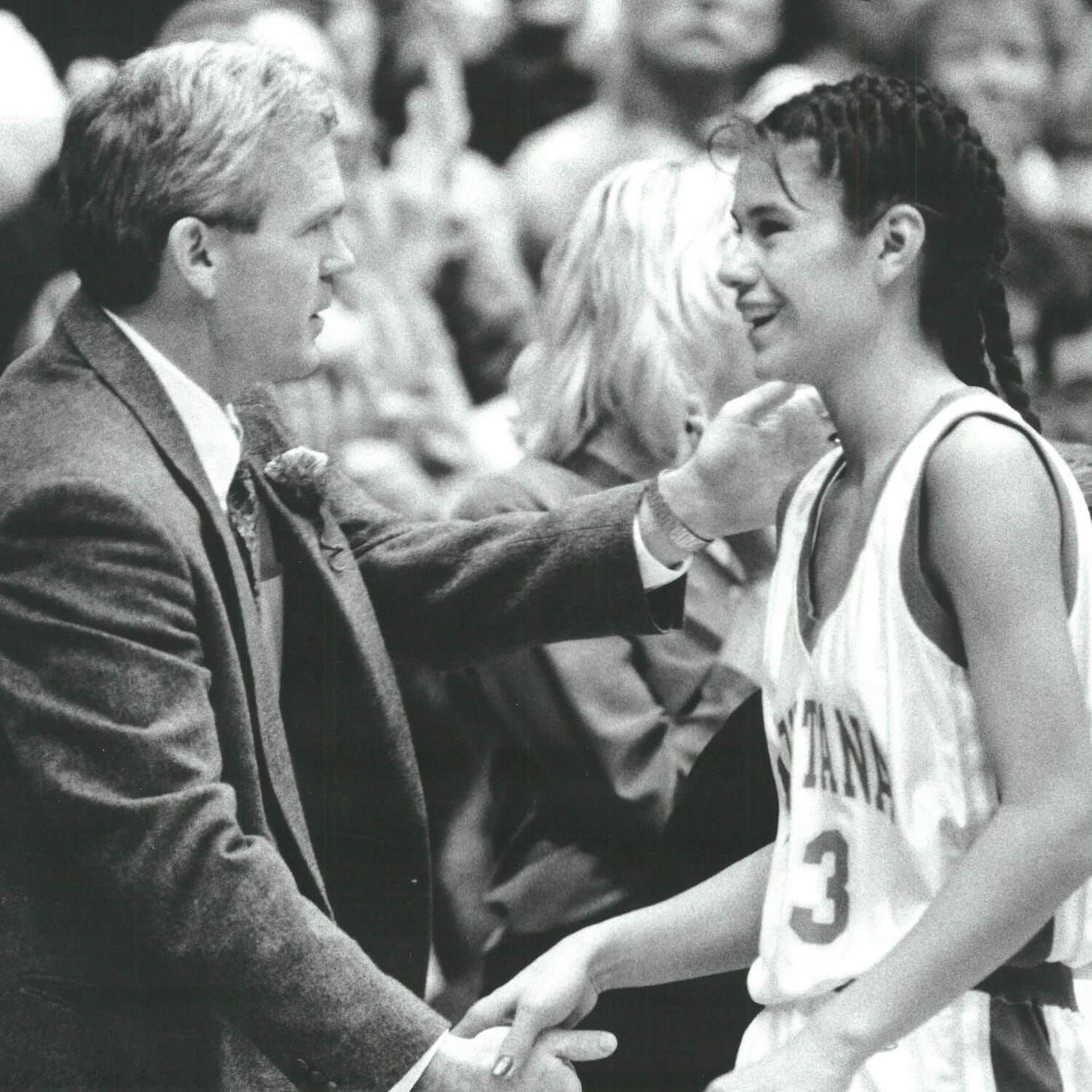

“She came to a basketball camp,” he remembers. “And I went and saw her play at Browning.”

Selvig was aware of the rez ball concept having played boys and men’s basketball in Montana but he came away impressed with her play and that of the Browning team as a whole.

“The interesting thing is that you think it’s unorganized,” he says. “There’s more organization than a guy would expect because it’s very fast, very wide open. At the University, we did not play rez ball.”

But even with that in mind, Malia had to wait and wait for a phone call from Selvig. There were scholarship offers on the table from Weber State, who flew her down to Utah, and Montana State-Billings, who were offering her the chance to play basketball and volleyball. It was coming down to the wire of signing day and then the phone rang.

“He was like, ‘you didn’t receive that information in the mail? to sign?’,” she recalls. “And I said no. He said, ‘well, do you want to play for the Lady Griz? Are you interested?’ and I said heck yeah!”

It didn’t sink in at the time but it was history made for Malia Kipp and Native American women in Montana. For the first time ever, a tribal woman in the state had received a full-ride scholarship to play Division I basketball. But what came next was complicated, not just for Malia but the women like Simmaron Schildt that would follow in her footsteps. They would have to leave the reservation and, for the first time, be fully immersed in American society.

Between Two Worlds

At one of her first Lady Griz practices, Malia had a feeling of how things were going to go. Coach Selvig had the team all lined up and told his players to pick out their shooting partners. Whoever paired up would be shooting together for the rest of the season. A pit started to form in her stomach.

“‘Oh great’,” she remembers thinking. “‘I’m the Native here that’s gonna get picked [last]. No one’s gonna pick me.”

But something happened that surprised her. Carla Beattie picked her before Malia could be picked last. From that moment until the end of their senior year, they shot together. It was a make-or-break moment for the freshman from Browning and from there on she felt that maybe it could work in Missoula. But quickly she realized how difficult it would become.

“There would be times when I would be talking and [teammates] would be like ‘are you talking Indian?’ because I had a really thick Blackfeet accent at the time,” she remembers. “I just didn’t feel that I belonged.”

It was an isolating experience, especially for Kipp, who had to be the standard bearer for an entire people. The first and only up to that point. Years later, Simmaron Schildt would face a similar set of circumstances.

“I didn’t understand why I felt so different,” explains Schildt, who played for UM about two years after Kipp graduated, “and it was more of a feeling than anything. Why don’t I mesh with these women? All of these women seem to just get each other. Why do I feel like I’m on the outside looking in?”

There were many factors that contributed to these feelings. Living away from the Reservation proved to be difficult for women like Malia and Simmaron, who had such a tight family unit and a major community that supported them back in Browning. Cultural staples like ‘Native humor’, a type of deadpan, dry delivery mixed with black comedy, didn’t exactly translate. But what made things most difficult was the isolation of not understanding why. It wasn’t until another Native joined the Lady Griz that Simmaron started to feel welcome.

“When LeAnn [Montes] joined the team, all of a sudden everything changed for me,” she says. “It was just an instant click. It changed the rest of the experience for me because we got each other.”

There would be no such opportunity for Kipp, who had to blaze her trail alone. She was supported by her own community and some Native friends from around the state that attended UM. There were friends like Carla Beattie that gave her small sense of belonging and Coach Selvig who tried to understand as he went. But they were small moments of comfort amid wide periods of loneliness.

“It was a total learning process for me,” Selvig explains. “It really was the white man’s world versus where they came from and their comfort zone and all their support system from the reservation.”

In spite of the challenges, Kipp persisted, buoyed by some words of wisdom from her grandmother: “She would always say, ‘you know, babe. God doesn’t put things in your way to break you. Those things that you perceive as burdens, they’re privileges because he knows you can do it.”

Kipp would go on to play all four years with the Lady Griz, taking parts in major NCAA Tournament upsets over 5 seed San Diego State in 1994 and 7 seed UNLV in 1995. In Browning and around the Blackfeet Nation she was something of a celebrity and a figure for people like Simmaron Schildt to look up to and eventually emulate. It would take years but eventually she and others would finally understand their time in Missoula and what they still mean to those in their own communities.

Native Now & Forever

The idea of being a Native-American basketball player on Montana’s campus was never something that was explicitly noticed or discussed, according to Malia and Simmaron. In 2002, Schildt’s final game in a Lady Griz uniform, the tribe performed an honor dance and gifted her a blanket.

“It was one of the only times it was even acknowledged,” she says. “I think that’s why I learned later on that we all had the collective experience of feeling alienated.”

It wasn’t until recently, when a Montana PBS documentary featuring Malia’s journey and groundbreaking time in Missoula was aired, that Schildt really understood the breadth and magnitude of what women like she, Malia, LeAnn Montes and others had done.

“That experience with the other women around that table changed my entire perspective of everything,” Schildt says, “because we had never talked about it before. And it normalized us in a way that I needed to be normalized because I didn’t understand why it was so different at the time.”

That journey of enlightenment continued at a 2023 Nike N7 Game. The initiative, led by Sioux and Assiniboine citizen Sam McCracken, aims to inspire Native American youth to participate in sports nationwide. It was at that event that the Native women of the Lady Griz were honored again.

“I could not believe how powerful that experience was,” explains Schildt, “because it made me realize that we had never been recognized. It felt like I was finally accepted in a way that I had never been and seen for the experience we went through.”

Robin Selvig would go on to continue recruiting Native women to play for his Montana teams and keep winning Big Sky championships until his retirement following the 2016 season. His 865 career wins are eighth all time among women’s college basketball coaches.

“I’d like to be thought of as an advocate for that community,” he says. “I wish I knew what to do to make things better. I think the fact that they go back to the reservation, I don’t look at that as a failure. I look at that as them going back to help other young kids learn that they can dream a lot of things and have a chance to go do them.”

Malia Kipp was able to live that dream and instill it in others. Her younger cousin, Shanae Gilham, was one such player that ended up playing Division I basketball. Montana State star Kola Bad Bear, who was a key part of the Wildcats 2022 NCAA Tournament appearance, credits Kipp with being the first to introduce a path.

"A lot of kids look up to her and see that milestone," Bad Bear told local Montana TV affiliate KTVQ. "They see the fact that she did it and accomplished it and set all of these stepping stones that they can do too."

“I do think that made an impression on Native athletes,” Kipp says. “I even had a couple male Native athletes say that when they saw that, they were like ‘Malia did it. We can do it too.’”

As more recognition came, it drew more eyes to rez ball and to the cultural significance of hoops to Native peoples from coast-to-coast. The idea of basketball as self-expression plays itself out in an especially pronounced way on reservations, from the elders in the stands to the kids on the court. It is a reclamation of self, of tradition, a positive warping of something introduced with malicious intent to a celebration of a culture that has survived in the face of unimaginable odds.

When someone goes to see rez ball, they might see shades of a dance on the hardwood. Through generations of struggle and disenfranchisement, there is joy and humanity. Where people see from afar the problems within reservations, watch a basketball game and see the resilience and love within a community.

“It just gave people something else to talk about,” Simarron says. “Just the sense of fighting, of being kind of like a warrior, in a sense. Fighting for recognition to be seen in a different way than you’re normally seen.”

And for Malia Kipp, the first tribal woman in Montana to play Division I basketball, rez ball will always be a dance. Within Blackfeet culture, what is known as a ‘fancy dance’ is among the most hallowed and time honored traditions that spans indigenous cultures on the plains and prairies of the American west.

“When Natives sing — like the tribal elders, you sing and you drum — you do it with your heart,” Malia says. “When you go out and dance, you do it with all your heart. You go out and play? Same thing. Do you get to go out and sing a song and you just like to sing it because you’re asked to sing it? No, you sing it because you mean it. You dance because you mean it. You play because you mean it.”

I was literally researching some info on womens history with HBCUs and I think your article popped up in the search. Great read. Now I will do more research on Native women in basketball/sports.