The Legendarium: Immaculate Hearts

In women's basketball, the first dynasty wasn't a major state university or deep pocketed program. Instead, it was a small catholic school from Philadelphia who took over the world in the 1970's.

Camilla Hall is a convent home on the campus of Immaculata University in Philadelphia. On days when the women’s basketball team played, elder sisters would crowd around the radio and listen intently. They knew each girl on the roster, had given them rosaries and sent them off to their games with a blessing. Huddled around an AM signal they would hang on the broadcasters every word. No one was rooting harder for the Mighty Macs, save for maybe the Lord himself. If things weren’t going well, the call would go out.

“The girls are in trouble.”

Legend has it that at that moment, the elder sisters would mobilize. With assistance from others in the convent, they would walk or be wheeled into the chapel.

And there, they would pray.

A Different Game, A Different Time

Marianne Crawford grew up in a row house on Golf Road, right on the border of Upper Darby and Philadelphia proper. Every day, she’d jump out of bed and head to the end of the cul-de-sac where the basketball court was. Sometimes she’d do her chores first and other times she’d go out to avoid them. When she’d get to the court she’d sometimes be alone, shooting the ball the way her Uncle Jack had taught her. Initially, the only way she could reach the basket was by shooting underhand. So he taught her to shoot like Rick Barry.

Some days, she would look to the east and peek through the Merion Terrace apartments and see the SEPTA train lines. If she got on that train and rode it two miles, she’d see Overbrook and West Philadelphia High Schools.

“That was the home of Wilt Chamberlain,” she says. “So I would stand on the court and look in that direction and think about the 1967 Sixers. Because, look for the women. They’re not there.”

For Marianne, and many like her at the time, their only frame of reference was men’s basketball. When they’d go to the playground they were, more often than not, made fun of for even being there. Sometimes they’d have to literally fight the boys to be allowed on the court.

After all, girls had no place playing five-on-five.

“The contention was, and this was from my physical education teacher that I had, that if we ran too much our insides were going to fall out”, said Cathy Rush, who grew up playing in a pre Title IX world.

So the powers that be came up with six on six basketball. Initially, it was restricted to three players on each side and no one could cross half court. Eventually, the women’s game evolved. Two players would stay on the offensive side of the ball, two on the defensive side and two that could cross mid court. For all intents and purposes, basketball was segregated into two completely different sports. As the world dramatically changed in the 1960’s and into the early 1970’s, five-on-five finally made its way to the women. In Philadelphia, that meant the Catholic League could rise to prominence.

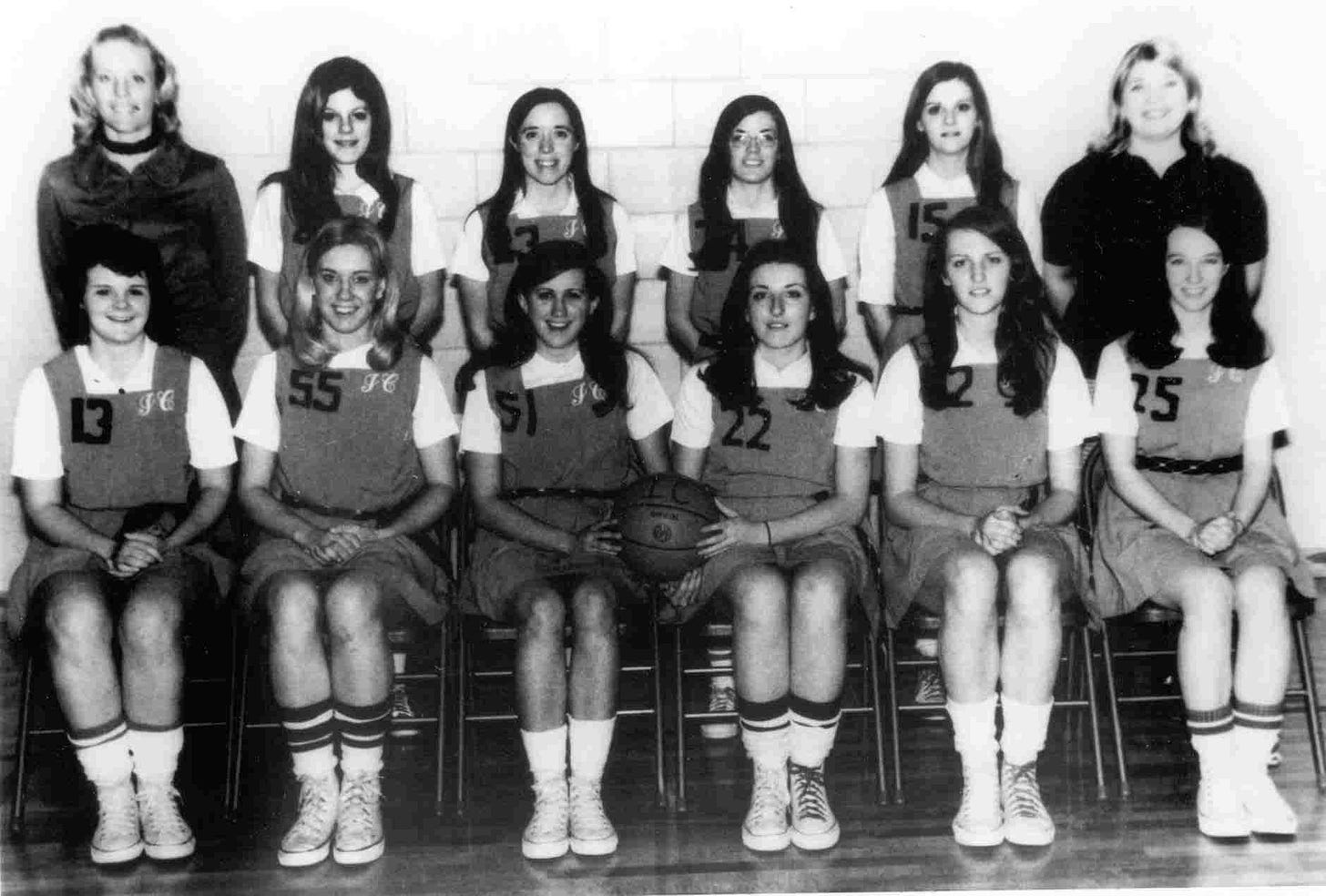

At the time, there were over a dozen girls-only schools in the city with over two thousand students per institution. An estimated 1.3 million Catholics resided in the metro area in 1970 while grade school enrollment peaked in 1964 at over 200,000.

“When you asked people where they were from, you’d ask what parish,” said Theresa Grentz, who was still Theresa Shank back then.

At St. Huberts, Archbishop Pendergrast, Cardinal O’Hara and others, a movement was growing among young women. They wanted to play basketball. Taking the cues of the original Big Five — Villanova, La Salle, St. Joe’s, Temple and Penn — the Catholic League played its’ league championship in The Palestra, UPenn’s iconic home venue. The games would sell out.

“8,000 screaming high school girls,” Theresa remembers fondly.

But outside of the league, the players had little to no idea of the sea change occurring nationally. All over the country, little pockets of rebellion flared up. A challenge to the status quo and the idea that women had no place on a basketball court playing five-on-five. They didn’t know it at the time but the girls of the Catholic League would be harbingers of change. When they went to college at Immaculata University, they didn’t have any intentions of being revolutionaries. They just signed up to play some basketball.

But then they met Cathy Rush and everything changed.

A Rush of Greatness…

When she arrived at Immaculata, 22 year old Cathy Rush was barely much older than her players. She was teaching elementary school and needed something to occupy her time while her husband, Ed Rush, refereed NBA games. So she decided to try her hand at a sport that she once excelled at. A sport that, as a teenager, was taken away from her.

Cathy grew up in southern New Jersey. In ninth grade she was the leading scorer not just for her basketball team but for all of Atlantic County. When she returned for her sophomore season, she found the district had cut all girls interscholastic athletics programs. Instead of organized team sports, they brought an outreach program from the University of Maryland called Gymkana, a troupe that “promotes healthy choices through gymnastics and acrobatic performances”. So for the next three years, Rush spent her time tumbling and vaulting, among other things. But basketball was always on her mind.

She decided to attend West Chester University in the Philadelphia area and upon arriving realized it was time to step back on the court. Her coach, Lucille Kyvallos, was one of the original pioneers of the game in the northeast and is now seen as the godmother of New York City women’s basketball. Quickly, Rush took note of her coach’s penchant for defying male authority. In 1965 the Amateur Athletic Union (or AAU), which was the only governing body that awarded a national championship, had their tournament in Gallup, New Mexico. In direct defiance of West Chester’s administration, Kyvallos and the team raised money to fly from Philadelphia to Kansas then to San Antonio and finally to Gallup. When they returned, Kyvallos had left to coach at Queen’s College.

Livid over what she thought was disrespect shown to her coach, Rush quit the team in solidarity and returned to gymnastics. But basketball was still there, always lingering in the background of her life. Years later, in what may as well have been an act of divine providence, Immaculata needed a coach and Rush needed something to do. It turned out to be a match made in heaven.

The Beginning of the Bucket Brigade

Rush’s star player, Theresa Shank, was originally going to go to Mount St. Mary’s college in Emmitsburg, Maryland on a full academic scholarship. But just before she was set to leave, her family home in Philadelphia caught fire and was destroyed. Realizing the needs of her parents and siblings, Shank stayed home and ended up going to Immaculata.

Around the same time, Judy Marra and her friend Rene Muth started at the university too. The high school classmates decided that it may be cool to try and play for the women’s basketball team. So they signed up.

“There was no feeling it would grow into anything,” Judy says. “We went to college for an education and there was no thought of women playing sports for anything other than fun.”

They had no weight rooms, no practice gym, no facilities of any sort. In Cathy Rush’s first year coaching in 1970, they didn’t even have a home arena.

“The sophomore class at the time had a cotillion and the decorations caught fire and burned the fieldhouse down,” explained Theresa. “So when we arrived on campus, there was no gymnasium.”

While Alumnae Hall was being built, Immaculata would have to play all their games on the road. They had no buses and no set daily schedule. Rush would get into her Volkswagon 411 station wagon and go straight from teaching to a game while the girls would work to figure out who could carpool and took anyone they could. On practice days, in what was called the ‘mother house’, they’d have to wait for the novitiates — nuns-in-training — to finish their recreation time before the team could begin. During the winter, Rush would leave the gym to find her car frozen. Everything off the floor felt like an immense challenge but success on the court, however, came surprisingly easy.

“I had the greatest player in America,” Rush says. “Early women’s basketball was dominated by one or two great players on teams and Theresa Shank, who was the greatest player of that era, was just so good. So much better than everyone else on our team.”

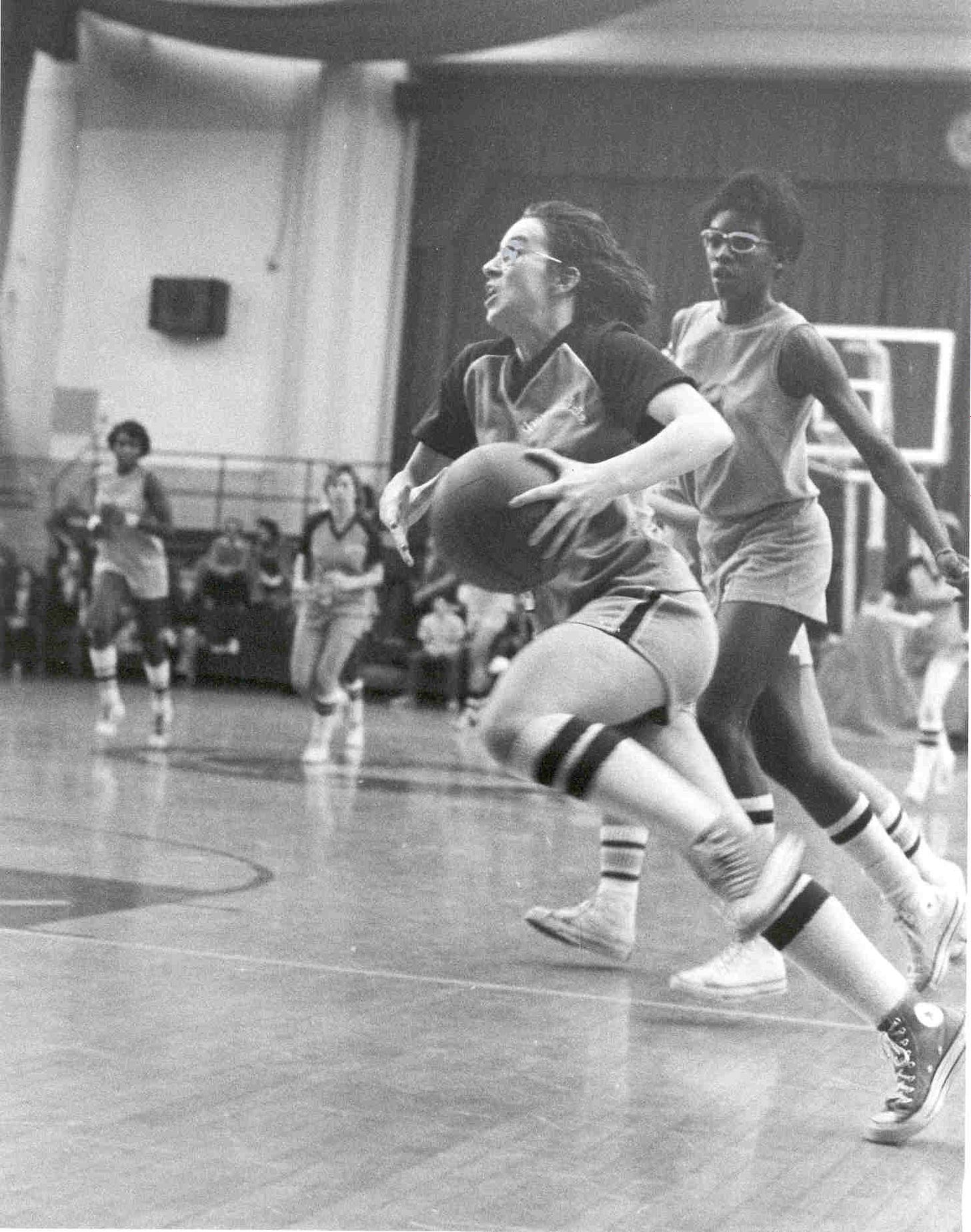

A 6 foot center who could play the post, run the floor and shoot a jumpshot, Theresa was something the game had never seen before. As longtime coaches in women’s sports scrambled to catch up to a five-on-five game, Cathy Rush utilized her husbands NBA connections and made a few of her own to turn Immaculata into a juggernaut.

“I had been doing all these coaching clinics on the side and I met Dean Smith, John Wooden, Bobby Knight,” she remembers.

She picked up press-defense elements from Chuck Noe, the Richmond innovator widely credited for creating the four corner offense Smith utilized at North Carolina. Offensively, they were one of the first women’s teams to play up-tempo and get out in transition.

“We played pretty fast,” says Judy. “With Theresa rebounding, she got almost every rebound so we could kick it out and run fastbreaks.”

In that first year, the team hadn’t caught the imagination of the greater Philadelphia area just yet. They were winning games but the idea of Immaculata as a powerhouse wasn’t even a fantasy. The girls were still responsible for bringing out folding chairs so people had places to sit in Alumnae Hall and after the game, Sister Florita — the nun in charge of facilities and cleaning and affectionately known as ‘Sister Mary Mop’ — would grab the microphone and tell everyone to put the chairs back on the rack before leaving.

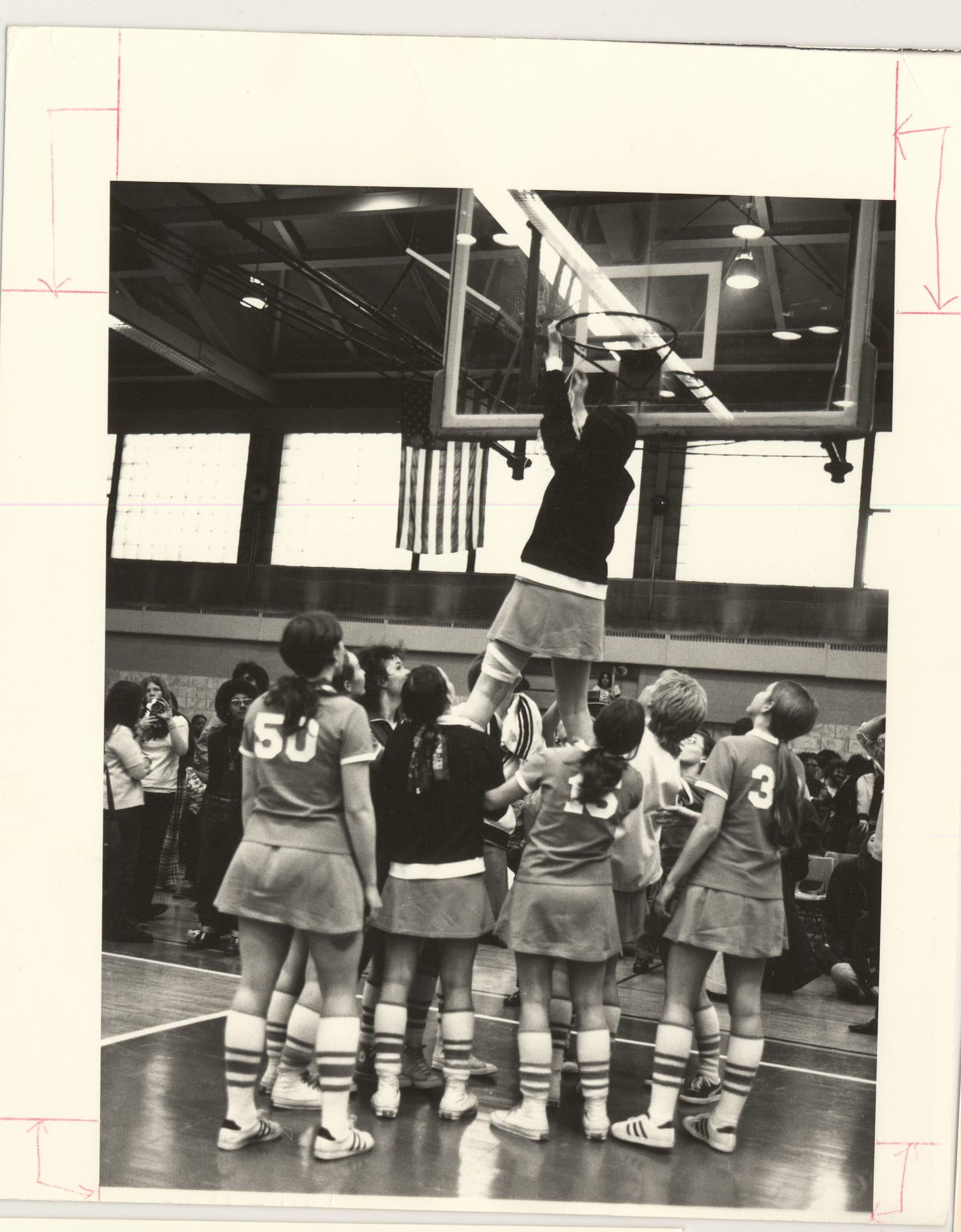

But soon, there would be too many people and not enough chairs. With Shank, Marra, Marianne Crawford, Rene Muth and others leading the way, Immaculata won consistently in their first year in Alumnae Hall. The sound of wooden dowels hitting aluminum buckets rang through the gymnasium. It was a trend believed to have been started by Muth’s father, who owned a hardware store and brought the bucket and dowel to a game to use as a noisemaker. Soon, the ‘Bucket Brigade’ would be a fixture at every game along with a few rows of nuns that would sit courtside in full garb, rosaries in hand.

The Macs finished their regular season 12-3 and ended up in the AIAW Regional Tournament. Then they met the dominant power of the era: Cathy Rush’s former school, West Chester University.

The Mighty Macs Shock the World

While the Immaculata players may not have known it at the time, they were a part of a revolution in women’s sports. Title IX had just passed and, in 1972, governance of basketball was handled by the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, or AIAW.

To get to the National Tournament, a 16 team bracket, Immaculata would have to finish in the top two of their regional tournament. To say it was a grind was an understatement.

“The games were played Thursday night, Friday morning, Friday night and Saturday morning so that’s how you got to the final game,” Rush remembers. “We had played three games in 48 hours [before the final] and my players were beat.”

West Chester, their matchup in the regional title, had been dominant since the days of the CIAW, a pre-Title IX governing body. The school had so much interest around their team that they were actually able to field multiple squads. In the regular season, they dressed mostly rotation players and reserves and were thoroughly handled by Immaculata. When the two teams met again in the regional final, the Golden Rams brought their A-team as well as their A-game.

“I was like ‘I thought we were pretty good’ and then we get blown out by West Chester” says Judy Marra with a laugh.

Despite a 70-38 landslide loss in the Regional, Immaculata still made the national tournament by virtue of the AIAW taking the champions and runners up of each region to fill the bracket. So they headed to Normal, Illinois but even that wasn’t easy. There was no fundraising apparatus for Immaculata, so Rush and the players had to lead a campaign to get the money to travel. By the end of the barnstorming, they had made about $2,500 and only eight players, along with their head coach, could go. They bunked four to a room and two to a bed. At the opening ceremonies, Indiana, Queens College, Long Beach State and others would arrive with full staffs, 12-15 players, some dressed in university issued warmup gear.

Then there was Immaculata, with 22 year old Cathy Rush and eight college students wearing Chuck Taylor’s.

But, against all odds, they snuck by Indiana, 49-46, then by Mississippi University for Women, 46-43, to set up a rematch with a West Chester team that ran them off the floor just a couple of weeks prior. But, with the prayers of the elder sisters of Camilla Hall spurring them on from back in Philadelphia, there would be no denying the Mighty Macs this time.

They ended up winning 52-48.

The Cinderella run was complete and the little catholic school from Philadelphia was a national champion. When Cathy Rush and her eight players got on the plane to head home, they were told their seats had been upgraded to first class and, upon arriving in Philly, were asked to wait to deplane. A crowd had gathered on the tarmac to welcome them home and the pilots wanted the team to be able to fully take it in. At long last, the city had taken notice and the Might Macs had officially arrived.

The First Dynasty Arises

Marianne Crawford was now a national champion but her pregame routine didn’t change. Before tip off, she did what every point guard does: dribble on the floor to find the dead spots.

“[I wanted] to know every floorboard in this place, so if people try to double team and trap you you know what places to avoid,” she says. “Just going back and forth and memorize that entire court.”

It was beautiful hardwood in a perfect venue. One that she, and her teammates, never thought they’d get the chance to play in. But it was 1975 and they were multi time national champions. The chance to be the first women to ever play at Madison Square Garden in New York City was an opportunity only afforded to a team of their caliber.

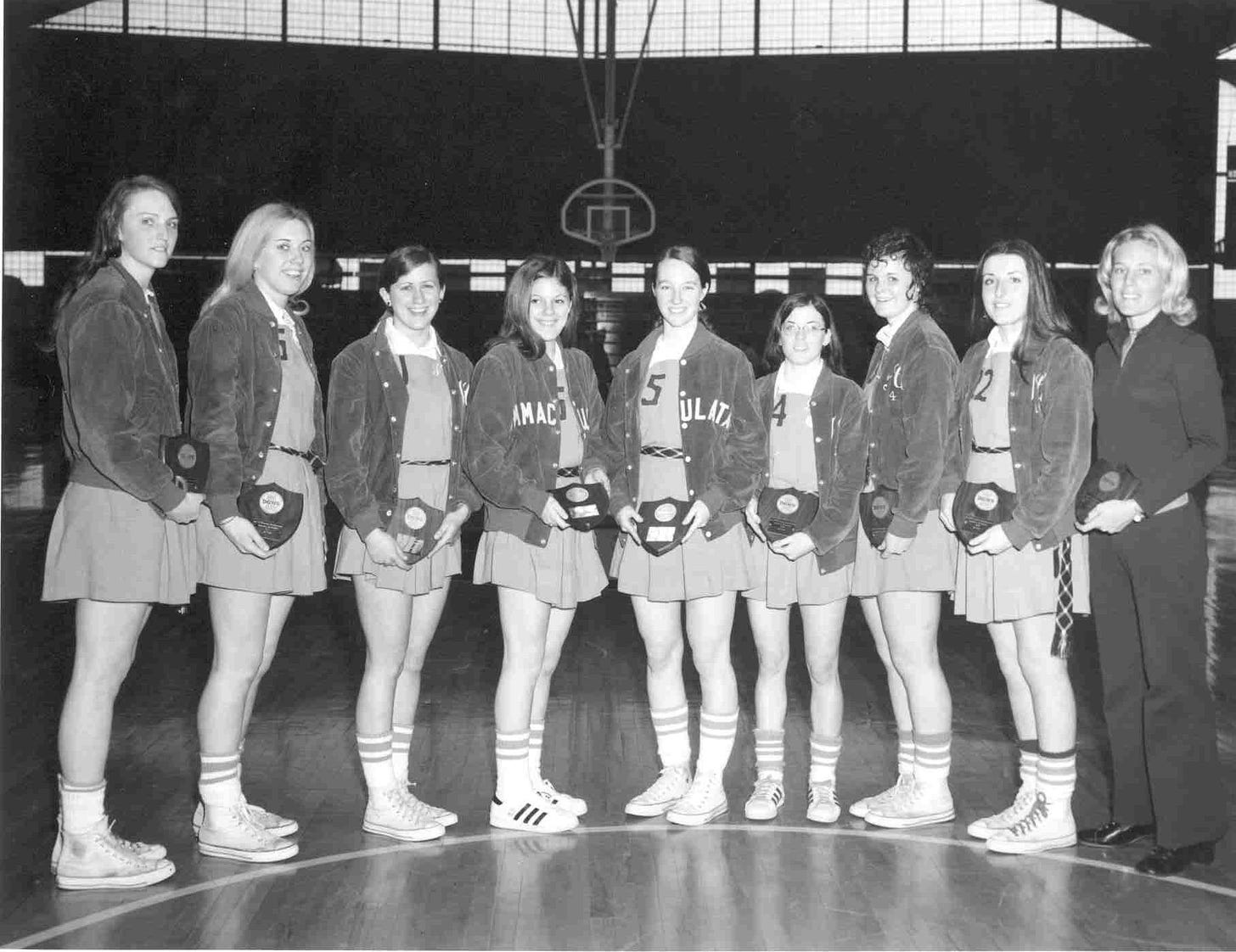

At this point, the Mighty Macs were a dynastic program in women’s college basketball. They had won two more national championships since their 1972 title win over West Chester and they were a known commodity in Philadelphia and elsewhere around the country.

“The professional teams in Philadelphia were not having their best years,” Theresa Shank recalls. “So they needed something at the time.”

Immaculata leveraged the catholic community in the city and found innovative new ways to get people to their games. Cathy Rush suggested that they rent out Jake Nevin Field House at Villanova. Initially, the university administration bristled at the $150 rental fee until Rush proposed putting up the money herself and she’d keep the gate revenue. Wallets opened rather quickly.

“So all of a sudden, every dad that had a little girl playing in the Catholic League would come to our game,” she mentions. “There were nuns in their full habits. And, you know, the buckets.”

The community support eventually turned into more coverage and groundbreaking opportunities. In 1975, Immaculata played Maryland in the first ever televised women’s basketball game in history.

“Being stupid, we won by [a lot] so I’m sure halfway through everybody turned the game off,” jokes Rush.

But while the players weren’t aware of the greater societal changes they were spearheading, they did understand the magnitude of the games themselves. They were selling out The Palestra, they played at The Spectrum, at MSG, in front of television cameras.

“The number of people that came to the game, to see us! To see Immaculata!” Judy explains. “I read that there was like 12,000 people for the game [at Madison Square Garden].”

She was close. 11,969 fans were on hand in Manhattan.

“We were not going to disappoint our teammates,” adds Theresa. “We were not going to disappoint our school and we were not going to disappoint our families.”

And for four years, they didn’t. They ran the women’s basketball world and a part of the city of Philadelphia. Theresa graduated in 1974 and Rush moved to a more press-defense style of play to try and make up for the loss in offensive production. But as Immaculata was once a disruptor in the world of women’s sports, other change agents were about to come for them as well.

When the World Caught Up

It was the spring of 1975 and Judy Marra was pretty confident that they could win a fourth straight national championship. Until she saw Delta State and, for the first time in what felt like years, her confidence slightly wavered.

“Every other game, I went into it feeling like ‘we got this’”, she remembers. “But I remember watching them and thinking ‘this could be a real test for us.’”

The Lady Statesmen, behind the dynamic 4’11 guard Debbie Brock and the dominant 6’3 center Lucy Harris, were emblematic of a new kind of basketball that was right around the corner.

“There wasn’t anybody like [Lucy] that we played against,” says Marianne. “They put all these shooters around this incredible center and it was really tough. You couldn’t play zone because they’d shoot the lights out but you couldn’t play man because no one could guard Lucy.”

In what was a shock to the world, the same way Immaculata once shocked West Chester, the three time defending champions fell in the 1975 AIAW Final to Delta State, 90-81. The following year the two teams met again in the title game. Behind another masterclass from Brock and Harris, the Lady Statesman beat Immaculata again.

“It was evident by ‘75 that if you didn’t have scholarships you were going to get left behind,” Rush explains.

She could see the writing on the wall at Immaculata. As the sport grew, it became more apparent to her that maintaining success at an all-girls school of less than 500 that wouldn’t offer athletic scholarships would be next to impossible. Bigger schools came calling. San Diego State’s athletic director would phone Cathy in the middle of Philadelphia winters and give her weather reports to entice her to move out west and coach. She talked with Rutgers and interviewed at the University of Maryland.

But she had her husband at the time, Ed, her children and a coaching clinic and players camp business that was taking off in Philadelphia. So in 1976, she went into the President’s office and told him that the next season would be her last. Immaculata fell to LSU in the Final Four and Cathy Rush decided to retire.

Three national titles, a 149-15 career record and an indelible mark on the players that she coached.

The Macs’ Mighty Legacy

To this day, every former Immaculata player believes that if Cathy Rush had taken one of those bigger jobs that she would be mentioned in the same breath as a Pat Summitt or Geno Auriemma. But she herself never really wonders.

“I was nominated for the Naismith Hall-of-Fame, I think five or six times,” she says now. “And I didn’t get in the first four or five times. So I got an email from [my son] that said ‘so sorry, again. You may not be a hall of fame basketball coach but you’re a hall of fame mom'.’ So I did the right thing.”

Eventually, she would be inducted in Springfield. In her speech, she joked that she’d lost less games in her career than the amount of times she’d been passed over for the Hall. While she stopped coaching in 1977, her players did not.

Rene Muth Portland was a four time Big Ten Coach of the Year at Penn State and led the Lady Lions to a Final Four in 2000. Theresa Shank Grentz went to Rutgers and bookended Immaculata’s legacy in the AIAW, winning the organization’s last championship in 1982. Marianne Crawford, now Marianne Stanley, went on to Old Dominion and won three national championships. The first title she won, Cathy Rush was on the television call.

“I just remember standing on the court and looking over at her,” Marianne remembers. “I’m thinking to myself ‘this is my homage for everything that you did for me.’”

Judy Marra married Phil Martelli, the now legendary coach of St. Joe’s men’s basketball. She herself was coaching at Villanova but decided with her husband that he would be the coach of the family. And with the benefit of sitting back, away from the day-to-day grind of the game, she is able to see the unique factors that made Immaculata a foundational force that fueled the revolution of women’s basketball.

“I think if West Chester had gone on and won [in 1972], it wouldn’t have been the same,” she explains. “It maybe wouldn’t have had the same feel as a small all-girls catholic school and something about that part of it makes it so different than anything else.”

Theresa agrees.

“When you throw in there the parishes, the schools, the nuns that were teaching in those schools had a connection to Immaculata, it all fit,” says Grentz. “It was perfect. It will never happen again.”

As does Marianne who now, with the benefit of age and wisdom, sees Immaculata through a broader prism of Title IX, the women’s rights movement and the social changes that started in the 60’s, crystallized in the 70’s and still continue today.

“At that time, some of what was going on was so big it was almost too big to think about,” she says. “It was happening so fast that it’s only through the lens of hindsight that you go ‘wow that was really big’. In a way, it’s like ‘what if Immaculata had never happened, then what?’ It would’ve been something else but would it have been as big, as monumental, as influential or indelible?”

As the Immaculata program has transformed through the years into Division III and far removed from the glory days of old, the legacy remains. The older nuns of today are the novitiates of then. And the prayer said by Cathy Rush and her team before each game is still said by the Mighty Macs players and coaches, all these years later.

O God of Players, hear our prayer

To play this game, and play it fair,

To conquer, win, but if to lose

Not to revile, nor to abuse

But with understanding, start again,

Give us strength, O Lord, Amen.