The Legendarium: Mother Margaret and the Darlings of the Delta

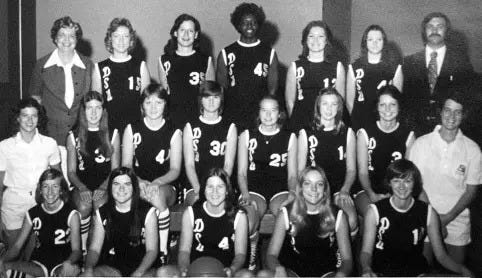

After the dominance of Immaculata in the AIAW, a new power emerged in the South. Delta State became a new dynasty, led by the tandem of Lusia Harris, Debbie Brock and Cornelia Ward.

At a four way intersection deep in the Mississippi Delta, an old brick building sits abandoned. If you’re driving on Highway 49E, you might miss it entirely. Winds howl through empty windowpanes as weeds curl between derelict garage doors. Turn westward on Old Highway 8 and you’ll see with greater clarity what was once here and what is now lost.

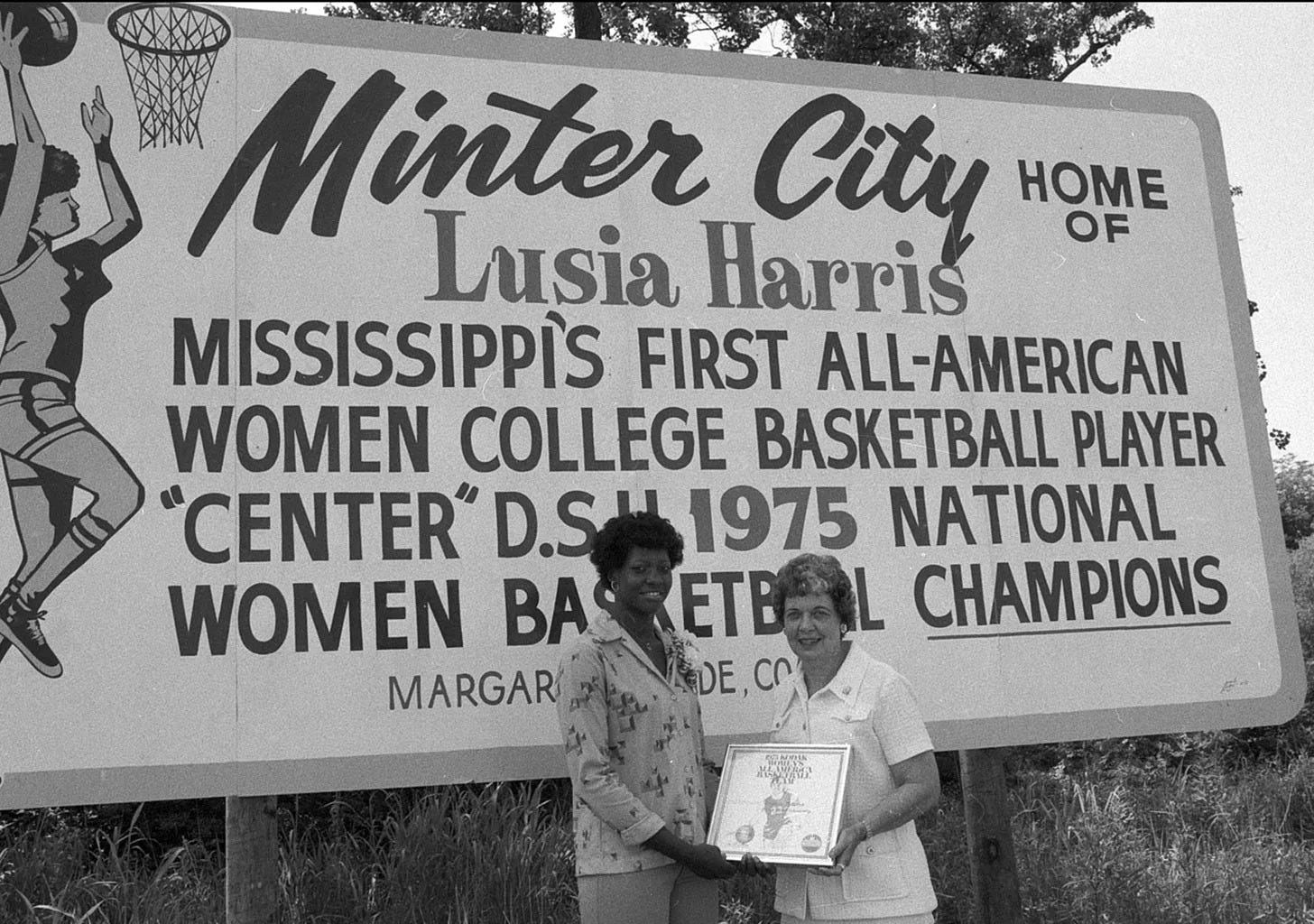

Just across the street, agricultural fields stretch for roughly a mile until you drive by marsh and thicket before eventually seeing open land again. Once upon a time, this was a bustling little town. Shacks and shanties housed sharecropper families while a mill employed many that lived in the area. Young children would play in the Tallahatchie River or walk to that old brick building to go to school. As time went by, a sign was erected on Highway 49E. It was as large as one you’d find on an interstate, but clad in white instead of green. The topline print welcomed visitors to Minter City, Mississippi but also told them the significance of the place they were entering.

Home of Lusia Harris

Mississippi’s first All-American women’s college basketball player

“Center” D.S.U. 1975 National Women’s Basketball Champions

On the banks of the Tallahatchie River

The Tallahatchie River headwaters begin up near Dumas Lake on the southern end of Tippah County in Mississippi. For over 200 miles, it snakes, spins and meanders westward until it empties into Sardis Lake before picking back up and continuing across Interstate 55. After it crosses past Batesville, the river officially becomes a part of ‘the Delta’ and once it does, the history behind the Tallahatchie becomes deeper, more turbid, and significantly more complex.

The Mississippi Delta is not the same as the Mississippi River Delta, the area in Louisiana where one of America’s great arteries empties into the Gulf of Mexico. No, the Delta is something different. It was the economic engine of the early South. Millions of slaves, some Native-American but almost exclusively African after the Indian Removal Act of 1830, tended to the fields and helped turn the upland areas of the Delta into some of the wealthiest in the United States. After the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of the Civil War, many of those Black families turned to sharecropping as a means of making ends meet. The lowlands quickly became synonymous with segregation and poverty. From the end of the 1860’s and on through the next century, Jim Crow was the law of the land. Many sons and daughters of former slaves went north to cities like Chicago and Memphis hoping to better their circumstances. But others stayed, working the fields, the factories, or in the homes of white families. Ethel and Willie Harris were two such people, working and residing in Minter City with their nine children.

In 1955, their tenth was born: a daughter named Lusia, who would later be called Lucy.

That very same year, just south of the Harris’ home and on the same banks of the Tallahatchie, the muddiness of the water turned darker and set the stage for a major cultural shift in the United States.

“The Till tragedy was something we didn’t talk about,” remembers Reverend Willie Williams, who was also born in Minter City in 1955 and now chairs the Emmett Till Interpretive Center. “I guess it was so harmful, so traumatic, that people just didn’t talk about it publicly.”

The murder of the 14 year old Emmett Till was a major catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement but in Delta Mississippi, it was a dark mark that went largely undiscussed. Minter City was roughly 12 miles from the town of Money, where Emmett Till was accused of whistling at Carolyn Bryant in a general store. As young Black children like Lucy and Willie grew up in the aftermath of his murder — in the late 1950’s and early 60’s — they didn’t know the gravity of Till’s story, or that it had even happened.

“The store that Emmett allegedly at that white lady, I didn’t know the history of that store but we used to stop there all the time,” Williams explains. “I had no idea this was the store.”

For over a decade and longer, the tragedy that began in Money, unfolded in a barn in Drew and concluded on the banks of the Tallahatchie were compartmentalized and tucked away in the minds of Delta Mississippians. Many young Black men that were alive in 1955 to see it, by Williams accounting, left for cities like Memphis or Chicago. Some even enlisted for the Vietnam War. But many, after that moment, wanted to get out of the state. For those that came after some parents, like Ethel and Willie Harris, made a concerted effort to give their younger children a chance to experience life without that trauma looming like a shadow over their existence.

“I think a lot of the things that were going on in Mississippi at that time, I was shielded from it,” Lucy told Valerie Still of the University of Kentucky in 2021. “I was just shielded either by my parents or other people that I was surrounded by.”

As a child she would wash her clothes in the Tallahatchie, unaware of the blood that once stained its waters. After school she would leave T.Y. Fleming and cross the street to her home then sometimes head to the field to work, picking seed cotton and stuffing it in a sack, to help support the family. But when she would have the time she, along with her siblings, would head to the side of the house where a basketball hoop had been constructed. They called it ‘the hill’.

Initially, she wouldn’t be able to play — she was now the second youngest of eleven — and would have to watch her siblings. But soon, she’d be picking up the ball in the evenings, learning the game and taking her first steps on a journey to transcendence.

Delta in the Delta

In spite of what some may think, there was a strong culture of girls basketball in Mississippi. It wasn’t like Kentucky or Ohio that had fallen victim to a 1930’s ban on interscholastic competition for girls sports. In fact, the Mississippi High School Activities Association can trace state champions back all the way to 1930, when Ponta defeated Vimville in the inaugural title game.

That culture permeated even past the high schools and down into elementary/junior high schools like T.Y. Fleming, where coach Molly Parker had to convince Ethel Harris to let her daughter try and play.

“I just gave in,” Ethel told the Clarion Ledger in 1976. “I had watched her brothers and sisters playing every night after suppoer and I didn’t want another girl playing. But [Molly] was a pretty good talker and I just said ‘yes’ to get her to shut up.”

As a child, Lucy inherited her mother’s height. Willie Williams, one of Lucy’s childhood friends who went to T.Y. Fleming and Amanda Elzy High School, believes that Ethel was between 6’0 and 6’1. Classmates and family would sometimes tease the 6’3 Lucy, calling her ‘long and tall and that’s all’. But eventually she proved that she was much more than that.

“[Amanda Elzy’s team] would demolish people, man,” Willie says. “They’d throw the ball to Lucy and she would put it up. At that time it was six girls that played in the women’s game.”

With Lucy running the show, Amanda Elzy would become a top team in the Delta, only losing 15 games in her three years playing. She would win three MVP’s, take them to the state tournament and scored a record 46 points in a single game. People were coming out to see Lucy and the girls play, just as they were in other towns across Mississippi.

“You were expected to play basketball if you went to school in Hatley,” says Cornelia Ward, who won four state championship teams from 1971-1974. “When I was in elementary school, I can remember going to the gym on Saturdays and the high school team was holding — I guess you would call it a clinic these days — on Saturdays for us to learn the game.”

Almost four hours away on the opposite side of the state, Mary Logue was playing in Vicksburg and developing a bitter on-court rivalry with a diminutive point guard named Debbie Brock.

“She was a little spitfire,” Logue says. “She learned all the tricks to the trade.”

Each had different paths to winding up in Cleveland, Mississippi. Mary had initially planned on going to Mississippi College for Women but her high school coach had alerted her to Delta, which had relaunched a women’s basketball program in 1973. So she called her best friend, Pam Piazza.

“I said, ‘where you going to school?’,” Mary remembers. “She said ‘Delta State’. And I said, ‘hey, you want to be roommates?’”

Cornelia Ward, on the other hand, had been recruited by several junior colleges in the state and some Mississippi four year programs that were just getting off the ground. But her coach, the prep legend Harry Adair, told her that it might be better to be with a program that was already established. As it happened, Delta had been up and running for a year. So before she did a practice walk for graduation, Adair stopped Ward and told her DSU assistant coach Melvin Hemphill was on the phone.

“[Harry] said ‘Hemp’s on the phone. What do you want me to tell him?’”, says Cornelia. “And I said, ‘tell him I’m coming’.”

But over at Amanda Elzy, Lucy Harris wasn’t nearly as certain. Her first desire was to go to the historically Black college Alcorn State. There was just one problem: Alcorn had no women’s basketball program. So she looked to the west, just a 30 minute drive on Highway 8, to a growing teachers college in Cleveland, Mississippi.

However and for whatever reason, Harris, Ward, Logue and others including Wanda Hairston, Ramona Van Boekman and Debbie Brock ended up at Delta State.

And it was there they met Margaret Wade.

“Give ‘em Hell”

Delta State women’s basketball began in 1925 but in 1932, the sport was deemed too strenuous for women. The powers that be in Cleveland decided that the program would be shut down and dropped from DSU’s interscholastic sports offerings. It offended everyone on the team, including a young Margaret Wade. As captain, she had to break the news to her teammates. So they gathered their uniforms, had a mock funeral ceremony, burned their jerseys and buried them.

Disappointed but undeterred, she played some semi professional basketball in Tupelo before entering the high school coaching ranks. For 19 years, she led Cleveland High and posted a record of 453-89. They made three straight state title games in 1946, 1947 and 1948, losing all three by a combined five points. After a brief retirement she came back to Delta, this time as the school’s director women’s physical education. For 14 years, she worked and waited, hoping that one day basketball might return to DSU. When Title IX passed, the moment had finally arrived.

“Our school president really was a visionary,” Mary says. “And he had no doubt who he wanted to restart that program at Delta State.”

Wade was a pretty quiet coach, as many remember. A tactician who possessed a keen understanding of the game, she was different than many of the elite early coaches of the time. Where someone like Immaculata’s Cathy Rush was only a couple years older than her players, Margaret Wade and Queen’s College head coach Lucille Kyvallos were seen as elder stateswomen using their experience to build champions.

“[Coach Wade] had a very warm personality,” says Cornelia. “She was very caring. She had the final say in everything we did but, most of the time, she let the assistant coaches run the show. Only time I remember her getting off the bench was maybe to call a timeout.”

Her trademark was a small insert that she would wear on the inside of her jacket for every game. Before tip off, she would flash it at her players. That was all it took. One glance at Margaret Wade’s jacket and those three words emblazoned on the inside pocket would carry the Lady Statesmen into battle.

‘Give ‘em Hell’.

A Delta Dynasty

Pretty quickly, it became apparent that Wade had a uniquely talented team in Cleveland. Harris, a 6’3 center, was the centerpiece augmented by the 4’11 Debbie Brock as well as Wanda Hairston and Cornelia Ward.

“We would run a double low post with Lucy and Wanda,” Cornelia recalls. “A high-low with three out kind of thing.”

In 1974, the roster immediately started to perform finishing 16-2 and narrowly missing out on the chance to play in the AIAW National Tournament. But it only provided fuel for that 1975 season, one in which the community of Cleveland started to fall in love with the team that had been named ‘The Darlings of the Delta’.

“The people in Cleveland and Delta State were phenomenal fans,” says Cornelia. “They had to change our times for the women’s games because men’s games would normally be the second game. But people would come and see us play and then leave. They wouldn’t stick around for the men and so they changed to us playing second.”

After beating everyone in their path across the state of Mississippi and Tennessee, the Lady Statesmen found themselves in the 1975 AIAW National Tournament. Their first opponent was an extremely talented team out of Washington D.C.: Federal City.

“They were physical,” Cornelia adds, “In a way that we were not used to. Not that we played soft in Mississippi but we didn’t have that kind of competition.”

Lucy got into foul trouble but Mary Logue had some major contributions off the bench to help Delta win 77-75 in overtime. From there, they beat Tennessee Tech, northeastern powerhouse Southern Connecticut State and set up a title game with the three time defending national champion Immaculata.

“Every other game, I think I went into it feeling like ‘we got this, we’re good’,” says former Immaculata star Judy Martelli. “But I remember watching them and thinking ‘this could be a real test for us’.”

The Lady Statesmen won their first national title, 90-81, dethroning the three time defending champs. After the win, DSU flew from Virginia to Memphis then drove back to Cleveland to celebrate. On I-55, it sunk in for Mary Logue what they were doing.

“We were coming back in our little vans,” she remembers. “There were fans that were lying along the highways and it was like ‘wow!’ and they were waving and honking. That’s when I realized the importance of what we accomplished.”

Almost overnight, Harris, Brock, Hairston, Ward and everyone else became sensations in Delta Mississippi. Every newspaper would write about the games, storefronts would shut down in Cleveland and the Lady Statesmen were celebrities on campus. Each player handled it differently. Harris, somewhat mercurial to her teammates, hung around her sorority sisters and kept to herself socially. But everyone on campus knew who she was.

“She was well known and identified and held in high esteem,” says Mike Kinnison, who played baseball for Delta starting in 1976. “The other thing I would remember about Lucy was just her modesty and her humility and how she went about her business.”

As one of the few Black students on campus, Lucy would reveal later in life that she did feel eyes on her.

“I walked into the cafeteria and all these people were just staring,” Lucy joked with Still in that 2021 interview. “And I said ‘what’s everybody staring at?’”

“I made friends real quick,” she continued. “We had pickup games in the gym and I made friends with and sororities. I became a Delta. So that became a close knit friend group. There was a lot of support mainly because we had so many fans. I think the fans wanted me to adjust and they wanted me to be happy.”

While on campus, she was named the schools first Black homecoming queen and, according to the Clarion Ledger, honored at a pep rally that was attended by most of DSU’s 3,450 person student body, many of whom skipped class to see it.

“I love school here,” she told the Ledger during that 1976 season. “It is not just going to class, there are so many other things here besides the books. Because it is smaller, everyone knows everybody else.”

With Lucy — the ‘Tower of Power’ — and a supporting cast of pro level players, Delta continued to win and raise their profile. They played a regular season home-and-home with Immaculata and split the series but the two would meet again in the 1976 National Championship. Again, the Lady Statesmen would topple the Macs and win their second national title. Quickly, the eyes of the sport shifted from Philadelphia to Mississippi.

“We began to go elsewhere,” Cornelia says. “We flew to New York City to play in the [Madison Square] Garden. We flew out to Las Vegas. It was getting bigger and better and people were starting to notice women’s basketball.”

Lucy was selected to the 1976 Olympic team, the first United States women’s basketball team to ever compete in the games, and scored the first basket of competitive play. She would go on to win silver alongside the likes of Carol Blazejowski and Ann Meyers-Drysdale, to name a few. When she returned to campus later that year, Delta State was becoming something of a traveling road show.

They hosted Long Beach State, Tennessee, Stephen F Austin and Louisiana Tech. The Lady Statesmen played at Wayland Baptist and Immaculata, traveled to Old Dominion and UNLV. And then, of course, they won the AIAW National Title for a third year in a row, defeating LSU 68-55 in the final.

It was a fitting bookend for Lucy, Wanda Hariston and Mary Logue, who all graduated that year. Cornelia Ward, Ramona Van Boekman and Debbie Brock had one more year to play. But there would be no four peat as Delta was upset by Valdosta State in the Region III Tournament, costing them a chance to play in the South Regional which was held in their home of Cleveland, Mississippi.

Much like it was with Immaculata, the tide of the sport was shifting towards larger state schools with broader reach. Soon, Delta’s time at the top would come to an end.

A life of Lucy and the mark of Mother Margaret

At the intersection of Highway 49E and Highway 8, it’s hard to imagine that Minter City once teemed with activity there. Across the street from an abandoned T.Y. Fleming school is an open field that grows a host of crops. The house where the Harris family once lived is now no more than an echo, whispering in the evening southern breeze on the Delta. There’s no more grocery store or department store. The post office has moved. Minter City’s cotton seed oil mill remains, collecting rust and serving as a reminder of what once was. The white sign welcoming visitors, the one that proudly proclaimed that it was the home of Lucy Harris, isn’t visible on Highway 49. But Reverend Willie Williams doesn’t need a sign to know the legacy his childhood friend leaves behind.

“I’m very proud of the fact that, knowing Lucy and growing up with her and in all the midst of all the resistance and the odds stacked against us,” he says, “that’s what motivates me today to know that we can do much better if we do things the right way. She was able to overcome those things and get out on that basketball court where she was free as a bird. She will forever be my hero.”

As the NCAA took over governance of women’s basketball, Delta State became another footnote of an era that the likes of Walter Byers and others were all too happy to erase. But down in Delta Mississippi, the impact of the Lady Statesmen is still felt and celebrated to this day.

“It just really captured this whole area,” says Mike Kinnison, now the athletic director of Delta State. “It did give us that credibility. At that point in time, we had as good a product as anybody in the nation and certainly in the state and we’re very, very proud of that. No question.”

Lucy was drafted by the New Orleans Jazz and given a chance to try out but she decided to focus on her family instead. Cornelia Ward — now Cornelia Ward Jones — played professional basketball in the WBL before it folded in 1981. Margaret Wade would retire soon after her three championships.

As every member of the Lady Statesmen chartered their own course in life without a professional league to aspire to, their legacy endured within Cleveland and their own communities. But the question always remained about what Lucy’s legacy would be and how she would be honored. The Wade Trophy, honoring the best women’s college basketball player in America, is named for Mother Margaret. Every member of those Delta State teams is in the DSU Athletics Hall of Fame while Lucy, Coach Wade and Debbie Brock are members of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame as well.

Sadly, in January of 2022, Lucy passed away at the age of 66. A memorial was held in the Coliseum that once cheered her name. Where she went 109-6 over the course of three years while breaking barriers for Black women everywhere in the Delta.

Following the release of the Academy-Award winning short subject documentary about Lucy’s life (titled ‘Queen of Basketball’), conversation arose about renaming Walter Sillers Coliseum after her. A petition, which included major luminaries like Shaquille O’Neal, multiple members of the Delta State athletic and academic community, politicians from Rosedale and Greenwood as well as Lucy’s teammate Wanda Hairston advocated for the name change.

To some within the DSU community, the former Mississippi politician was known as ‘Mr. Delta’ and the university’s key patron and biggest protector in the legislature. But to others, Sillers was an ardent and unapologetic segregationist. He took the lead within the legislature to found and fund Mississippi Vocational College in Leflore County as a means to deter Black students from attending Delta State and forestalling integration of the school.

That school is now called Mississippi Valley State, a well known HBCU. On their campus lies a building that houses the department of fine arts: the Walter Sillers Fine Arts Building.

But perhaps most ironically, Sillers himself wrote to Governor Hugh White in 1959 opposing the bonds that would eventually go towards building the coliseum that now bears his name.

Much like the rivers that meander through the Delta, the discussion of that arena in Cleveland is murky and takes time to traverse.

Alternatives have been discussed, such as a garden and bench honoring Lucy in front of the arena. A statue of Coach Wade stands outside the coliseum while the court is named after Lloyd Clark, who maintained Delta’s dominance winning three Division II national titles in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Is there any space there for Lucy Harris in any capacity? Her childhood friend, Willie Williams, hopes so.

“The revolutionary type of thing happening in women’s sports now, it’s amazing,” he says. “But Lucy did that way [back when] — we’re talking about — I’ve been out of high school for 50 years!”

“She brought history to that Coliseum,” adds her old teammate Mary Logue.

For now, the legacy of Lucy Harris, Margaret Wade, Cornelia Ward and Wanda Hairston, Ramona Von Boekman, Debbie Brock, Mary Logue and others is preserved in columns and newspaper clippings. But where it truly flourishes is rooted in something more intangible; a proof that women’s basketball could bloom where seeds are planted and water is provided.

“We were like a flower,” says Logue, “and the petals were going out towards other states and we made enough impact that other players said ‘well, I want to go down there and play.”

From the stem of Delta State eventually came the likes of Van Chancellor’s Ole Miss and Vic Shaefer’s Mississippi State. The torch lit in the Delta was eventually taken up by Pat Summitt’s Tennessee then shared by Andy Landers’ Georgia and Joe Ciampi’s Auburn. Like contemporary music can trace its roots to the blues and spirituals that originated in the fields of the Delta, so too can many aspects of women’s basketball find their homes in Minter City, Hatley, Vicksburg and Cleveland.

And even if that sign in Minter City is hidden within the willows, if not gone completely, there will always be a legacy to be shared of Mother Margaret, the Lady Lusia and the Darlings of the Delta.