The Legendarium: Pauley Prodigies

No Cap Space WBB's 'Legends of March' historical series rolls on with a look at the first major university to win a women's basketball national championship and how the UCLA Bruins changed the game.

Ann Meyers woke up on the morning of March 25th, 1978 in a good mood.

She was at home in Los Angeles, it was her 23rd birthday and she was playing for an AIAW National Championship.

Her older brother David had won title games on some of the best college basketball teams ever assembled by arguably the greatest coach of all time. She had watched him reach the mountaintop and felt that it was her turn.

Ann’s UCLA Bruins played plenty of top teams in her career but this particular matchup was special. The Maryland Terrapins were becoming a rival on the women’s side the way they were in men’s basketball. NBC came to Los Angeles to televise the game for the first time ever. And, as it happened, the game consisted of two major state universities for the first time in a post Title IX world.

Whatever the result, the matchup was a statement to the world that women’s basketball was here to stay.

So Ann headed to Pauley Pavilion and decided that she and her team would be the ones to make history.

The New Wave in L.A.

In the 1970’s, Los Angeles was a central figure in a nationwide culture shift. For decades, the city had been defined by paradoxes. A land of milk & honey, free from the segregation of Jim Crow yet defined by exclusionary and racist public policy. Old Hollywood dominated the landscape with progressive films and performances all while blacklisting legendary writers accused by Joseph McCarthy of communism. The preceding five decades leading into the 70’s created a city of contradictions and many within its’ limits were struggling to rationalize the two.

The response was an explosion of political enthusiasm, righteous anger and stands against the status quo. In Los Angeles, a long history of feminist activism — one that began with figures like Caroline Severance and Maria Guadalupe Evangelina de Lopez — was reaching new heights, with new faces and in new places. Against the backdrop of Title IX, Billie Jean King beat Bobby Riggs in the now-legendary ‘Battle of the Sexes’ in 1973. That same year, artist Judy Chicago helped found the Feminist Studio Workshop in L.A., eventually taking over a vacant building near MacArthur Park that came to be known as The Women’s Building.

“I’m in high school at the time,” says Ann Meyers-Drysdale, “and so I’m very aware. Those are different times and there was a lot of upheaval and a lot of people looking for equality.”

While she was still young and not yet of an age to upend the status quo, Ann was already on a path to become a pioneer in her own right. One of 11 children by Patricia Ann and Bob Meyers, Ann was always encouraged to get outside and play sports. Her oldest sister, Patty, was eight years older than Ann and considered one of the best athletes in the entire family. Competition between the brothers and sisters was natural, which would sometimes lead to friction when the Meyers girls would go out and expect the same type of openness to competition at school.

Ann would always make sure to grab a basketball before recess in elementary school and get shots up with the boys. By fifth grade, hoops was introduced as an after school sports program but with one major caveat: there would only be one and girls would not be allowed to play. While most parents would shrug their shoulders and tell their daughters that it’s just the way of the world, the Meyers parents were different.

“Unbeknownst to me — because I'm what, 11 years old or whatever — my parents went to the school to talk to the teachers [and] talk to the principal,” Ann says. “[They] had to go to the superintendent [of the] school district and other people to be okay for me to play on the boys basketball team, which obviously they did get through.”

Ann would get to play on AAU teams in California as a young teenager while her sister Patty split time between basketball and softball. She’d see elite up and coming players like Marian Washington, elite programs like Wayland Baptist and Nashville Business College and get the opportunity to play against the best the sport had to offer.

But she wasn’t alone in her story. All over California, there were young girls just like her that were challenging the standard and soon would get an opportunity to make history as Title IX came into effect.

Up in the Sacramento area, in a small college town called Davis, Denise Curry was getting the opportunity to make some history of her own. The daughter of a long time coach, Denise was 13 years old when Title IX legislation was passed at the federal level and while most schools would take a few years to recognize it and act accordingly, Davis was unique. Girls that were in one of the two junior highs could try out for the high school JV team.

“I was a recipient of [Title IX] fairly early compared to people a bit older than me, for example,” she says. “We had a principal and superintendent who were, at least, were looking our for girls in some capacity much more so than I think a lot of other places.”

In some other places, that type of equality had to be earned outside of school environments. On 22nd and Cooper St in South Central Los Angeles, Anita Ortega was making a name for herself on park blacktops. She didn’t start playing until she was 14 years old and used the game as a form of escapism in inner city L.A. She would watch the boys play when she was in junior high and would wait and wait until she had the chance to get on the court with them.

“I watched them play for months and months and months before they decided to let me play,” she recalls. “I finally convinced them like, ‘give me a chance to play. Don’t worry about me. You can’t hurt me.’ And in that moment, I started playing with the guys.”

As each of them found their path to basketball in different ways, all roads led in some way, shape or form, to UCLA.

How Billie Became A Bruin

The Bruins women’s basketball program had gone through a couple of changes by the time most of the top players arrived in the late 1970’s. Former UCLA men’s basketball star Kenny Washington was the first head coach of the program in 1974. He was a part of two national championship teams under the legendary John Wooden in 1963-64 and 1964-65 and it stood to reason that he’d have the ability to lay the groundwork for the Bruins women’s program.

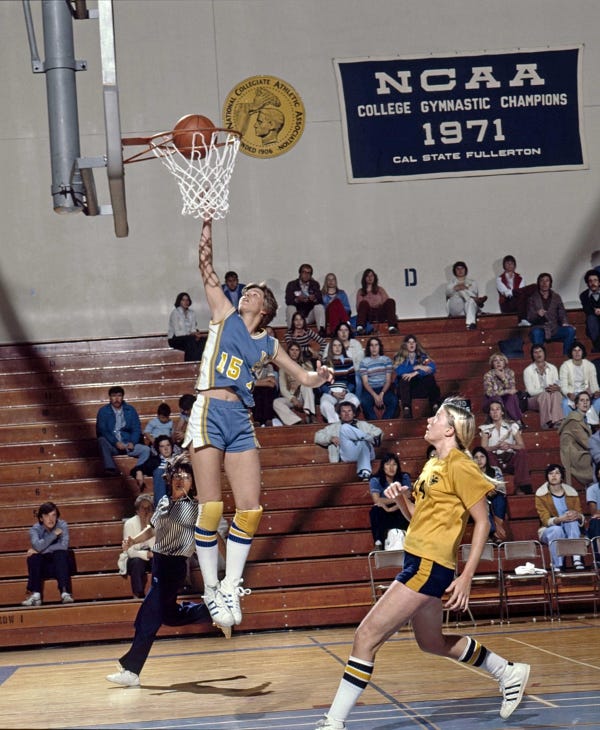

He got a nice boost in his first year, as Ann Meyers decided that she would make attending UCLA a family affair as her older brother Dave was already a household name among Bruin fans. He was a national champion in 1973 and 1975, anchoring a frontcourt with Bill Walton and Jamaal Wilkes. But Ann’s path to getting into school was a bit of a story unto itself.

“I didn’t take the SAT’s,” she says. “I didn’t know what those were because I was always — in ‘74 as a senior in high school — I made the [USA] national team and so I was traveling and stuff. So I got into UCLA and I had a difficult time getting my student card and being registered for the dorm and getting meal tickets because I hadn’t passed academically.”

So, at a tournament in Santa Barbara, she missed one of the games to head to San Marcos High School to take the SAT and move forward with her academics at UCLA. The school offered her a scholarship and she became the first woman’s athlete to be awarded a full ride to the school in its’ long history. During her freshman year, the brand new Bruins went 18-4 but Kenny Washington wouldn’t be retained. Instead, Ellen Mosher, who made a name for herself in Iowa women’s basketball circles and was a long time AAU player, took over the program.

“Why was Kenny let go? I have no idea,” says Ann. “A lot of us as players were upset about it, but we don't understand what goes on in different phases and different people making decisions and so forth.”

The following year, Anita Ortega joined the program almost by accident. She had been accepted as a student to go to USC but ended up at UCLA because they offered her an academic scholarship. As the first one in her family to go to school, the choice became easy. During the mid 1970’s, the concept of recruiting players on scholarship to play women’s basketball was not yet a part of the exercise. In Anita’s case, and in spite of her accomplishments in L.A.’s public high school scene, she found a sign on campus asking girls to try out for the Bruins women’s team.

So she went to the gym to give it a shot.

Alongside both guards was a 6’1 forward named Heidi Nestor, a cowgirl type from the San Fernando Valley, who had played some junior college ball before joining the Bruins.

With Ortega, Nestor and Meyers leading the way, the Bruins went to two straight AIAW Regional Tournaments but lost before they could make it to the national tournament. They ended up in the NWIT where they would lose in two straight finals, both times to Wayland Baptist.

Which prompted UCLA athletic director Judith Holland to act. The story goes that the Bruins had beaten Cal State Fullerton 74-48 in the regular season in 1976, prompting Mosher to brag a little bit about her program being better than Titans coach Billie Moore’s. It wasn’t a slight so easily forgotten and when the two met again with a chance to go to the AIAW National Tournament on the line, Cal State Fullerton beat UCLA.

Holland decided she had seen enough. Ellen Mosher was let go shortly after and Billie Moore was hired.

“Some of the top players played for Ellen because she kind of set the tone about work ethic on the court,” Anita says. “But Billie came in with more of an organized fashion.”

By the time she arrived at UCLA, Coach Moore was already well known throughout the country. In 1976, the IOC introduced women’s basketball to the Olympics and Moore would be the first head coach of Team USA. On that team was Delta State’s Lucy Harris, 17 year old Nancy Lieberman, UT Martin’s Pat Head (who would come to be known as Pat Summitt in the ensuing years) and UCLA freshman Ann Meyers, Moore’s future starting guard.

During that time there was no gold medal game or knockout rounds for the women. Instead, a single round robin group format determined the winner and the Soviet Union, long the dominant force in the sport internationally, took home the gold medal handily. But the experience was a formative one for Meyers, who returned to Westwood with Moore prepared to finally get over the hump and make them champions.

“She took no prisoners," Nestor says of Moore. “But she also had an amazing amount of empathy and understanding of the team [and] each teammates personalities. She was clear clear about what each one of us had to give. And she got it out of each one of us.”

Big School Underdogs

It was the summer of 1977, and Denise Curry felt a bit like a fish out of water. She had just graduated from Davis High School outside of Sacramento and was making the drive up to North Lake Tahoe for a United States junior national team tryout. Standing alongside her in the layup lines was Nancy Lieberman, fresh off a 1976 Olympic trip with Denise’s future UCLA teammate Ann Meyers. It initially felt daunting, to be a high school graduate playing against guards with international experience of that magnitude but she eventually got settled.

“I played well that summer,” Denise says. “I think it toughened me up. That kind of helped me get ready for my freshman year at UCLA.”

When she got to Pauley Pavilion, the Bruins weren’t necessarily a well-oiled machine just yet. Moore was still learning every player’s strengths and weaknesses, trying to build a system and how to get the most out of every player.

Moore’s style was intense and Ann’s familial history with the head coach didn’t help matters. Her oldest sister, Patty, had a tenuous relationship with Moore when she played on Cal State Fullerton’s CIAW title team. It took Ann a bit to warm up to Moore. But it was clear that once she did, the rest of the team would follow.

“She was a tremendous teammate,” Denise says of Ann, “Only cared about the team and being successful and being a great teammate.”

“We had a totally different style of play,” adds Anita. “I was more flashy and speed and double pumps and Ann was more of a fundamental player. We complemented each other and in the end we, as a team, went on to bigger and better things.”

But before the season even started, tragedy struck. Cyd Crampton, UCLA’s 6’3 forward who was being groomed to be the next frontcourt star, was in a car accident. She broke both her legs and wouldn’t play that season. Nestor, who had been down and out of the lineup — “floundering”, as she put it — was thrust back into a starting role.

Ten games into the season, it didn’t feel as though the Bruins were poised for anything. On a road trip to the east coast, UCLA lost three games to Delta State (in Madison Square Garden), Maryland and NC State. The loss to the Wolfpack was particularly crushing, as it dropped the Bruins to 6-3 in their first nine games.

But that adversity proved to be a crucible for the team. From Ortega to Meyers to Curry to Nestor, the Bruins showed a unique resolve and resilience. The Bruins dominated the likes of Long Beach State, USC, Cal State Fullerton and Stephen F. Austin.

“We had some come to Jesus moments internally,” recalls Nestor, “and we had it on the road. We understood [that] we played these big teams that we needed to play at the end of the season.”

By the time March rolled around, the Bruins were rolling. They headed up to Stanford for the AIAW West Regional and an all-time great matchup against Joan Bonvicini’s Long Beach State.

“Had it not been for that steal at Stanford against Long Beach State, I don’t think we would’ve made it to the Final Four,” Anita says.

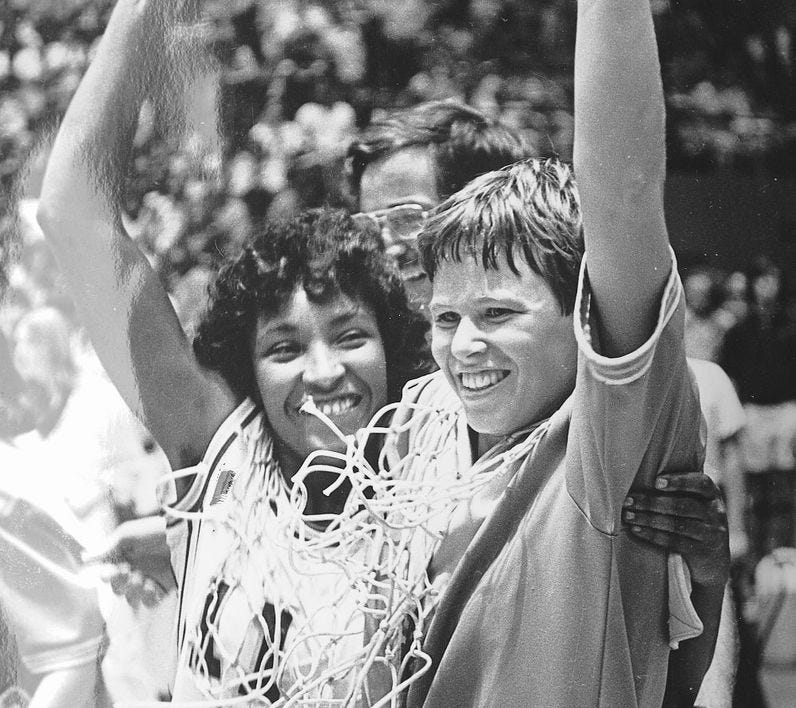

Indeed, it was her steal and layup in the closing moments of the game that tied the score and sent both teams to overtime. Meyers and Nestor hit some clutch baskets and the Bruins won 79-78. From there, UCLA rolled. They beat UNLV handily, qualifying for the AIAW Sectionals. They then beat BYU by 45 points and Stephen F. Austin by 26.

Easy work. Onto the Final Four.

The games would be played at Pauley Pavilion, the first time a national women’s basketball tournament would be held on the west coast. Because of L.A.’s status as one of the largest media market, newspapers and major networks started to take interest in the AIAW Tournament. While they still weren’t front page news — Denise says their articles in the L.A. times were the size of sugar packets — NBC opted to pick up the championship game and televise it, a first in women’s basketball history.

“I thought that could have been the turning point,” Anita says of the interest.

Their semifinal matchup was against Montclair State, a smaller college from New Jersey led by Carol Blazejowski, “The Blaze”, one of the most prolific scorers in the history of women’s basketball. Billie Moore knew that the dynamic forward would get hers but she didn’t want to alter a game plan around trying to stop her.

“She didn’t really subscribe to a lot of scouting,” says her longtime assistant Colleen Matsuhara. “Her mantra was ‘it’s what we do and we do it better than the other team.”

Blazejowski would go on to score 40 points in that game while Meyers led UCLA with a 19 point, 14 rebound, 8 assist effort. Adding to the hype was a crowd of over 7,000 fans that were on hand in Pauley Pavilion. The men had lost in the NCAA Tournament already, bringing many of the Bruins faithful back and putting all their hope into Meyers, Ortega, Curry, Nestor and the rest of the team to eight clap to the promised land.

Eight Claps

Ann Meyers woke up on the morning of March 25th, 1978 ready to go. It was her birthday and there was an opportunity to win a national championship. Standing against them was the Maryland Terrapins, who had beaten the Bruins in Miami back on December 30th.

But now UCLA was at home, in the comfortable confines of Pauley Pavilion with thousands of fans at their back.

“It was just a feeling,” Matsuhara remembers, “There was just something in the air. It was going to be a great, great day to be a Bruin.”

The alliteration wrote itself that day. Meyers the Masterful. Meyers the Magician. Meyers the Magnificent.

“Once the game starts, you’re so into it,” Ann explains. “I do remember when Billie pulled me out there were like, two minutes left, and I was so angry sitting on the bench.”

Moore had decided to try and get Meyers one final standing ovation from the Pauley crowd. She walked to the bench, as UCLA led in the fourth quarter, having finished with nearly a quadruple double in the national championship. 20 points, 10 rebounds, 9 assists, 8 steals.

“I don’t care about applause, I wanted to play to the very end,” adds Ann.

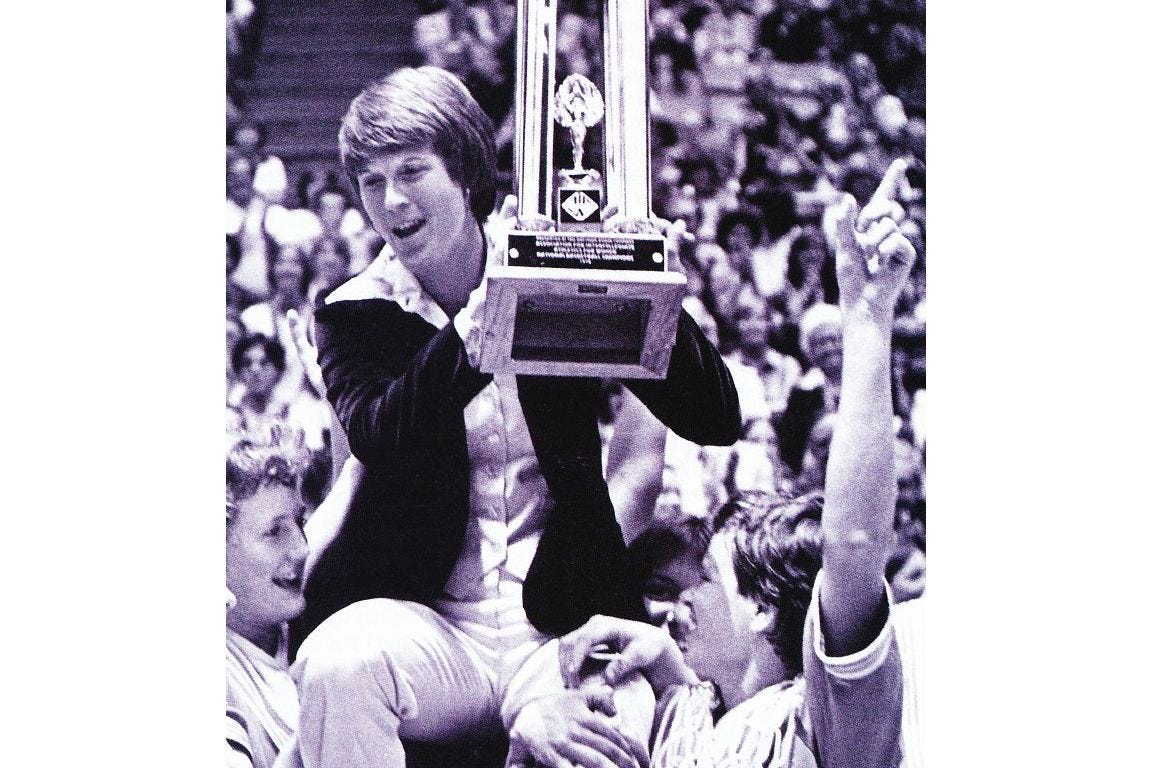

The Bruins beat Maryland 90-74, claiming their first national title in women’s basketball and were the first major university to do so. For the first six years of the AIAW’s life, titles had been won by Immaculata and Delta State only. Once UCLA hoisted their trophy, the sport immediately changed forever.

“I think it was huge,” Denise says. “I think there was a shift and realization that if you care, if you invest, if you give the opportunities, you’re going to get something out of it.”

Meyers star continued to ascend as she left UCLA with a title in hand and soon made international headlines as the first woman to ever receive a tryout from an NBA team, signing a $50,000 no-cut contract with the Indiana Pacers. She would also join the WBL, one of the first true professional women’s basketball leagues in the United States, and would be the Co-MVP for the 1979-1980 season.

Ortega would join her in the WBL, garnering All-Pro honors with the San Francisco Pioneers.

Denise Curry would go on to become UCLA’s all-time leading scorer and rebounder, guiding the Bruins back to an AIAW Final Four in 1980 where they would fall to eventual champion Old Dominion.

That title season would be the only one for Billie Moore but she would still find continued success. In 1981, the Bruins made the national quarterfinals with a young multi-sport star named Jackie Joyner. But the rest of the sport was beginning to catch up to the early pioneers of the AIAW. Fading away was Immaculata, Delta State and Wayland Baptist and coming into the foreground was Tennessee, USC and Georgia.

“[1979] was when it definitely started to change,” Anita says. “And from that point forward you have the Connecticut’s and Georgia’s and Texas’ and that too is, to me, important because I think the world started to take women’s basketball more seriously.”

But within the celebratory nature of that achievement is a feeling of sadness over the NCAA’s seemingly ruthless takeover of women’s basketball. While coaching records remained, player scoring records or achievements were wiped away because they occurred during the AIAW. Ask any member of the Bruins title team and they’ll say their biggest pet peeve is hearing broadcasters say UCLA has never been to a Final Four.

“It can’t be understated that the AIAW is what built this,” Heidi, who goes by Rive Nestor now, explains. “Women built this. Judi Holland was such a big factor in all this. She was so smart, she was so savvy and the AIAW engine was huge and it just got obliterated all of a sudden.”

While Meyers’ legacy is widely celebrated alongside legends like Nancy Lieberman and Cheryl Miller, even she laments the erasure of her peers like Curry, Ortega or any of the other stars of that era, from Lynette Woodard to Carol Blazejowski.

“All the coaches are recognized,” Ann says. “Pat Summitt, Andy Landers, Billie, you go on and on, all their recognitions. You take those AIAW [wins] away and they don’t have those records. But they don’t recognize the athlete.”

But as UCLA heads to their first *NCAA* Final Four, the legacy of that AIAW national title team gets a moment to live once again. For Ann Meyers, Denise Curry, Anita Ortega, Rive Nestor, Dianne Frierson, Cyd Crampton and everyone else on that team and involved with the program to be remembered for the history they made.

As prodigies of Pauley, Westwood wunderkinds and the proud owners of the only banner in the Pavilion that’s gold with blue lettering.