The Legendarium: Team of Destiny

Jody Conradt and Donna Lopiano had a vision. The 1986 Texas Longhorns had a dream. Together, they created a cultural movement in Austin and a season that is etched in NCAA history books forever.

Andrea Lloyd believes one of the last images she will see before she passes away will be of a car driving in the Frank Erwin Center.

Nicknamed ‘The Drum’ for its exterior appearance, the arena seats were configured in a bowl around the hardwood floor with a single tunnel leading out of the building. Through most of March 30th, the venue sat silent. The action was taking place over a thousand miles away in Lexington, Kentucky.

But as the news trickled out, the buzz on the University of Texas campus started to build. Around midnight, Lloyd and her Longhorn women’s basketball teammates arrived at the Erwin Center expecting a small crowd to congratulate them on a big win. Instead, they arrived to over three thousand people cheering at the top of their lungs. Lloyd, who had white-knuckled the NCAA national championship trophy since the team left Kentucky, turned her attention to the tunnel and saw them. The six seniors of the Lady Longhorns, atop a Cadillac convertible with a pair of horns on the front grill.

The car drove onto the floor and dropped them off. The cheers intensified. At long last, she parted with the trophy while upperclassmen from Kamie Ethridge to Fran Harris took turns basking in its’ glow. Barbara Jordan, the powerhouse pioneering U.S. representative, got on the mic and welcomed the team home.

The undefeated NCAA champion Texas Longhorns.

The Team of Destiny.

Lone Star Ladies

Jody Conradt is as Texas as Texas gets. She was born in 1941 in Goldthwaite, a small town a little under two hours from Austin. When she was ten years old the University Interscholastic League, or UIL, announced the first state basketball tournament for high school girls. Comanche, a town 30 minutes from Conradt’s home, won the inaugural Class A championship. That same year the Amateur Athletic Union — AAU for short — hosted their national tournament in Dallas. Many of the teams were clubs sponsored by corporations while a small handful of colleges and universities nationwide fielded varsity women’s basketball teams.

Texas had escaped the cataclysm of the late 1930’s and was able to build generational participation in the sport. Interest groups, who believed women shouldn’t be playing sports competitively, successfully lobbied several states, from Ohio to Kentucky to Oregon, to ban or slowly kill interscholastic competition.

But in Texas and other southern states, club teams persisted. The Galveston Anicos, a team sponsored by American National Insurance Company, won the AAU National Tournament in 1938 and 1939 before clubs from Nasvhille and Atlanta took over the scene. It wasn’t until 1954 that Texas returned to national prominence, only this time it was a university instead of a privately funded club team.

“Wayland Baptist was well known,” Conradt remembers. “It was the one school that you get a scholarship and have your secondary education paid for.”

From 1953-1958 the Flying Queens won 131 consecutive games and 10 AAU National Titles. While Jody was a star basketball player, averaging 40 points per game in high school, she didn’t end up adding to Wayland’s run of dominance. Instead, she went to Baylor University to get her bachelor’s degree before spending some time teaching at Midway High School in Waco and eventually earning a Masters. Then a call came from Huntsville, Texas.

“My first collegiate job was at Sam Houston State,” says Conradt. “I was going to coach sports, which were pretty much glorified intramurals, but I also had teaching responsibilities. So my first job, I taught seven activity classes and coached three sports.”

The entire budget for women’s sports was around $1,200 and she had one rule: if a player had a car, they would automatically make the team.

“We needed it to go to the games!” she jokes.

After compiling a 74-23 record at SHSU, Conradt moved to the Dallas Metroplex to coach the UT Arlington Mavericks. The draw? She wouldn’t have to teach anymore. She would, however, still coach three sports: basketball, softball and volleyball. It was a lot but Conradt enjoyed the change of pace each season. In just three years, the Mavericks went from 9-14 to 11-14 to 23-11. With the advent of Title IX in 1972, the women’s sports world was at a crossroads. Programs were ramping up all over the country to compete and win national titles. Immaculata and Delta State were the dominant teams of the AIAW’s early years but soon the likes of Tennessee, Indiana and UCLA were knocking on the door.

Texas wanted to do the same and one day, Conradt got a call. Not from UT Athletic Director Darrell K. Royal, but from an Italian-American woman from Connecticut who was, by Jody’s affectionate account, “the pushiest Yankee that I’d ever known.”

She didn’t know it yet but in time, together, the Yankee and the Texan would build a juggernaut clad in burnt orange.

For Women, By Women

Donna Lopiano found herself on the top floor of the Westgate Building in Austin, ready to meet a God.

The daughter of Italian-American immigrants and a multi time AAU national champion softball player, she came to Texas to interview for a job. In 1975, as Title IX took full effect all over the country, the Lone Star State’s flagship university decided to split their athletic department in two.

“Darrell Royal was the head football coach and the A.D. of the men’s athletic program at Texas and he didn’t want anything to do with women’s athletics,” she recalls. “Not that he didn’t like women’s athletics but he had a full time coaching job. He had a full time AD job. He didn’t want the added burden of raising money for women’s athletics.”

So here she was, interviewing to run a totally separate department at Texas. For women, by women.

All she had to do was get the blessing of Darrell K. Royal. Only there was one problem: he wasn’t on campus for her interview. He had forgotten and was at the Headliners Club, the legendary and ultra exclusive private club in Austin. So he told the executive leadership of the University to come to him.

It was Darrell K. Royal, so they did.

As they stepped out of the elevator, they were told it was a men’s only club. But Lopiano, giving her future Texas colleagues a preview of what was to come, wasn’t fazed.

“I said ‘sir, we’re with Darrell Royal,.’ And they let us in,” she says proudly.

So they sat down and the King of Austin walks over. The man who was the President of the American Football Coaches Association who, along with Southwest Conference President J. Neils Thompson, fought the federal government to exclude football and men’s basketball from Title IX. What on earth might he say about women’s sports? And how did Donna plan to respond?

“The first question he asked me is, ‘do you like country western music?’” says Lopiano. “I’m a Yankee and my response is instantaneous. ‘No’, I said. ‘I hate it’.

The interview committee was stunned. Here was Darrell K Royal, famously best friends with Willie Nelson, believed to be no friend to women’s sports, being talked to so frankly by a woman from Connecticut.

It turned out to be a match made in heaven. Royal gave the blessing and Texas hired Lopiano.

Now, she had to get started with hiring her own coaches. There was one from UT Arlington that was doing pretty well and worth an interview. So Donna picked up the phone and called Jody Conradt.

“I was skeptical,” Jody remembers. “[I thought] ‘can I put all of my professional career and all my life on coaching one sport?’ Because you look at the men’s sports and you know that they come and they go, so is that gonna be a problem? So Donna and I negotiated that I would actually coach two sports. I would coach volleyball and basketball and that happened for a couple years until I became the full time women’s basketball coach.”

Quickly, the two realized they had a unique opportunity at Texas. Without oversight and potential roadblocks being created by a male Athletic Director, they had the freedom to experiment and try new things to build enthusiasm for the programs. In short, the segregation of the department was a bit of a blessing.

“There was never a conflict with men’s athletics,” said Lopiano. “We just picked a different branding message and it was a God-send.”

But in order for Texas women’s sports, and basketball in particular, to resonate in Austin they had to do one thing.

“It was important that they win,” Lopiano says. “One of the first things I did was speak [at the] Texas Alumni Association. And [former Texas Secretary of State] Ed Clark asked ‘how long do you think it’ll take to realize a successful women’s athletics program?”

“And I said, ‘I’ll bet you we win the National Championship within three years. I’ll bet you a bottle of St. Emilion.”

It was a bet that looked like it would pay off early. In 1978-1979, the Longhorns went 37-4 but would lose to Louisiana Tech in the AIAW Regional. For the next few seasons, Texas dominated especially in the Frank Erwin Center. Off the floor, Lopiano, Conradt and team SID Chris Plonsky tried to build UT women’s sports into a brand.

But as 1980’s began, the AIAW found itself under siege. The NCAA was looking into bringing collegiate women’s sports under their umbrella, kicking off a bitter battle between Lopiano, the President of the AIAW and the NCAA’s leader Walter Byers. She believed that any negotiation of rules had to start from scratch if the governing body of college sports was going to take over women’s athletics.

“It’s rules are geared solely to male athletes,” she told the New York Times in 1981.

That same year, a vote passed that would allow the NCAA to hold championship events for women’s basketball. While some allege it was back room dealing that put the NCAA over the top, Lopiano isn’t sure. What she does know is this: the vote spelled the end of an era as Byers desire, she says, to control all of amateur sports was nearing completion. Many top programs, from Cheyney State to Louisiana Tech, would be going to Virginia for the new Tournament. Others, like Rutgers and Wayland Baptist opted to stay in the AIAW and try to win one last national title. With Lopiano as one of the leading figures of the organization, Conradt wondered what Texas would do.

“She and I had a rather heated conversation,” Jody recalls. “I wanted to play in the NCAA Tournament where the best competition [was]. It was perceived as the best competition. As I sit now, and since that time, I’m really pleased Donna’s idea prevailed. We did stay with the organization that had been responsible for providing opportunity for women.”

“The attitude was that we were going to challenge and fix the NCAA since we could not any longer control our organization,” adds Donna. “It was like a good fight, an advocacy fight.”

Texas made it to The Palestra and lost to Rutgers in the 1982 AIAW National Championship, the last in the organization’s history. The next season, they entered the NCAA with everyone else.

That’s when the show really started.

Branding Burnt Orange

By 1983, Jody Conradt’s Longhorns were a known commodity in Austin. She and Lopiano created ‘The Fast Break Club’ which would be the first set of season ticket holders at the Erwin Center. After each game, the club would meet and talk with Coach Conradt and her players.

“The accessibility of what you would think normally are inaccessible people was defining,” says Lopiano.

It helped that the team was almost exclusively comprised of local talent that fans wanted to talk to. Oddly enough, the strict UIL high school rules meant that Conradt and other Texas based coaches had a near monopoly on some of the best talent in the United States.

“They had a rule that you could not go out of the state of Texas to play and if you were an individual player, you could not go to a camp,” she mentions. “So that created an environment where nobody knew about this wealth of talent in the state of Texas.”

One by one, the top players made their way to Austin.

“We dreamed of going to ‘The Drum’ in Austin to win a state championship on the campus of the University of Texas,” says Kamie Ethridge. “So Texas was something very much in my vision.”

“If you’re going to get a great education and be at a baller school, a school that was going to right by women’s athletes, Texas was the only place,” Fran Harris adds.

Both were native Texans, Ethridge from the Lubbock area and Harris from Dallas. In 1980, they played one another in Austin for a 4A state title. Fran was the star of South Oak Cliff (a team coached by future hall-of-famer Gary Blair), leading them to a 74-49 win over Kamie’s Monterey to cap off a perfect 40-0 season. The next year, it was the senior from Lubbock hoisting a UIL state championship trophy.

In 1983, they joined All-American Annette Smith and Wade Trophy Finalist Terri Mackey. They made an Elite Eight and then another. Lopiano and Conradt capitalized on the success of their local stars and drew a connection between them and the women across the state.

“We were one of the first teams in the country to have media guides,” Harris remembers. “We had in game entertainment, we had [The Fast Break Club’] and some of the things people aren’t doing today, we were doing.”

Soon, celebrities and luminaries started arriving to the Erwin Center. Ann Richards, the future Governor of Texas, would come to games and meet the team. Barbara Jordan was a fixture near the scorers table. Players would go to events and rub shoulders with the likes of Dionne Warwick.

“I was surrounded by people that were influential and shaping the game,” says Andrea Lloyd, who joined up with the team in the fall of 1983. “It was hard for me to recognize that coming from outside of that, where that isn’t the norm.”

The women around the program, from Lopiano to Conradt to Plonsky and the powerful women cheering them on, were a major reason Lloyd came to Texas. Raised in Alaska by her grandparents and playing in Idaho, she had an aunt who lived in Fort Worth. There was some familiarity between her and Conradt, and the program sold itself the rest of the way.

The influx of talent was obvious and the Longhorns dominated the Southwest Conference, winning 40 straight games in conference play through the 1984-1985 season. That year, in particular, felt special to a lot of the players in Austin. From January 31st and deep into March, they were the number one team in the country. Their only two losses were on the road at Old Dominion (90-80) and in Los Angeles to USC (73-71). It felt predetermined that the Longhorns would be get over the Elite Eight hump, into the Final Four and contend for a title.

Until ‘The Shot’.

A Shot to the Heart

“I just had a flashback,” Fran Harris says over the phone. “I’m looking out the window and I see the ball go in. [Lillie Mason] jumps up. She goes up, [the ball] goes in.”

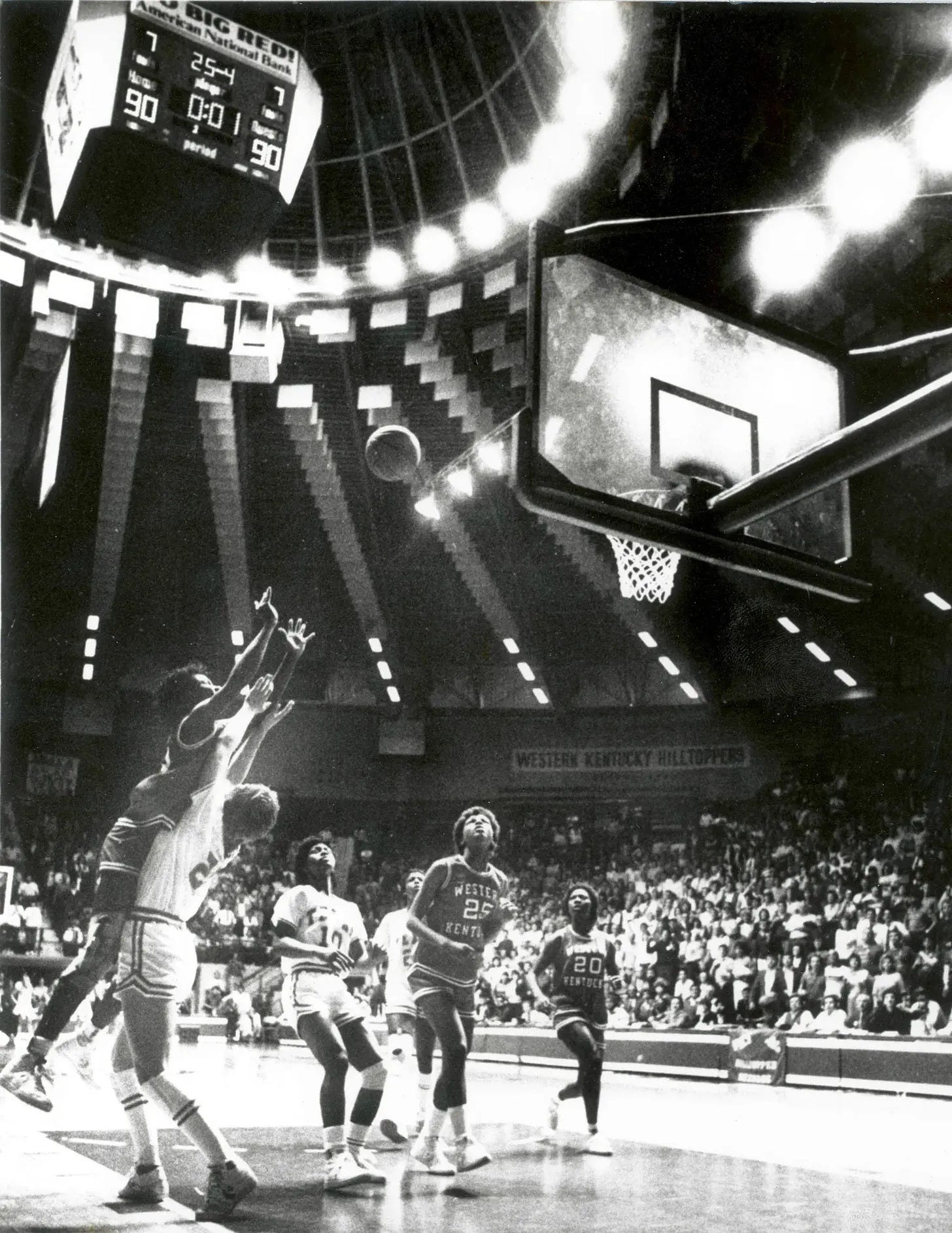

Lillie Mason’s buzzer beater in E.A. Diddle Arena was one of the biggest shots in women’s college basketball history to that point. It stunned the No. 1 Longhorns who thought a couple easy wins in Bowling Green would help them cruise back to Austin where the 1985 Final Four was being held. Instead, they stood stunned on a floor in Kentucky.

“I just remember sobbing and sobbing,” remembers Andrea Lloyd. “I don’t think I stopped crying for days.”

Western Kentucky would go on to defeat Ole Miss and head to the Final Four at the Frank Erwin Center. Ever the glutton for punishment, Jody Conradt sat in the stands of her home arena and watched the team that beat her play in a national semifinal.

“I very definitely remember coming back home and facing those thousands of people who had bought a ticket to the Final Four and sitting in the stands and watching somebody else win on your home floor, watching another team climb on the ladders and cut down the nets,” she says. “That set the tone then for a very difficult and long summer and offseason.”

There would be no down time in Austin between April and October. Only work. All six seniors — Audrey Smith, Annette Smith, Fran Harris, Kamie Ethridge, Cara Priddy and Gay Hemphill — set the tone. When freshman Clarissa Davis arrived on campus, she could sense it immediately.

“They had something to prove,” she recalls. “They were very, very intense in their training and in workouts. I’m just competing at a high level and I don’t want anybody to break me. I don’t want to be the little freshman not knowing so that’s sharpening me even more.”

A San Antonio native who was one of the top players in the nation out of high school in 1985, her aunt had played for Wayland Baptist and eventually Northeast Louisiana (now UL Monroe). As a middle schooler, a coach told her she could be in the Olympics. By the time she was ready to choose a school, it was between two time national champion USC, two time national champion Louisiana Tech or Texas, who had just been upset in the Sweet Sixteen.

“I saw USC on TV and they won the championship,” says Davis. “And I told my Mom, ‘in order to be the best you’ve gotta beat the best.’”

Senior guard Kamie Ethridge could see Davis’ talent immediately.

“She was one of those athletes that she could come out right now and she’d be a superstar right now,” she says. “She had to come off the bench and that says a lot about her as a competitor but by the end of the year, you literally could throw the ball anywhere near her and she could go make a play.”

Every day, The Shot flashed in the minds of the Longhorns players. Over and over. A months long torment finally gave way to actual games and the 1986 season. They would leave no doubt, some players believed. But it wasn’t until the first win of the year that Jody Conradt started to believe it.

Destiny Calls

There were no easy non-conference schedules back in the 1980’s. Many coaches, from Conradt to Pat Summitt, Andy Landers to Linda Sharp, believed that the best way to grow the game was for top teams to give the public a show.

The Longhorns entered the season number one and played all but one unranked team in the first two months of the season. They opened the year in Columbus against No. 10 Ohio State. Fran Harris hit the game winner, shooting left while on the right baseline.

“We barely eked by with a win,” Conradt remembers. “And it was so emotional in that game. It was like the exorcism. We gotta get that last season out of our head.”

“I never thought that way,” jokes Andrea Lloyd, who was now a junior. “We weren’t losing that year period. Doesn’t matter who it was.”

No. 10 Ohio State - W 78-76

No. 9 Tennessee - W 74-52

No. 3 Northeast Louisiana W 68-54

No. 4 USC W 94-78

Rutgers (Who finished No. 5) W 81-63

No. 8 Mississippi W 57-46

No. 7 Northeast Louisiana W 70-65

No. 20 Houston W 92-66

“It built momentum as the year went on,” Ethridge says.

That season, the average attendance at the Frank Erwin Center doubled, cementing the Longhorns as the biggest draw in women’s college basketball. They would remain top of the attendance rankings for the rest of the decade.

Win after win, the goal came more into focus. They went undefeated in Southwest Conference play, beat Missouri by 41 in the opening round of the NCAA Tournament before dispatching Red River rival Oklahoma by 16. Then came a knockdown-dragout Elite Eight game against Van Chancellor’s Ole Miss that they won 66-63.

“The pressure to get to the Final Four, I think that is the game where most people feel it the most,” adds Ethridge. “We had so much talent that we didn’t have to rely on any one person.”

As if the basketball Gods had written the story themselves, Texas headed to the Final Four in Lexington, Kentucky to beat the team that dashed their dreams the year before: the Western Kentucky Hilltoppers.

“We wanted revenge,” says Lloyd.

Western star Lillie Mason got into foul trouble early and Texas took advantage.

“We did a better job of scouting them the second time,” Conradt mentions. “We discovered Lillie Mason only turned one way. So everybody on our team had a little piece of adhesive tape on their left hand, little finger which was a reminder that if you’re guarding Lillie Mason, take a half step to your left which means a takeaway.”

The game wasn’t close.

No. 5 Western Kentucky W 90-65

Now came USC, the 1983 and 1984 NCAA champions. Their roster, from Cynthia Cooper to Cheryl Miller, was as deep as Texas’ and one of the most legendary collections of talent in collegiate sports history. Beyond the talent on the floor, there was plenty of underlying cultural battles happening between the teams as well.

“The differences, geographically, were astounding,” describes Harris. “I’d never been to California so all the stereotypical things you think about California — ‘oh, they’re so Hollywood, they’re so plastic’ — those were real. Same thing about them coming to Austin, they think we all wear cowboy hats and wrangler jeans.”

The juxtaposition of ‘Good Ole Texas girls’ vs. ‘West Coast Swagger’ played out in the press. Whereas the USC players wore their confidence on their shoulder — “we’re the coolest shit y’all have ever seen,” as Harris describes them — the Longhorns came in with a different motto: “Don’t mess with Texas.”

They led the Trojans 45-35 at halftime but entering the locker room there was still some tension. Everyone felt the pressure of what was to come. Except for one senior: Cara Priddy.

“She was sitting in the corner … and she is sort of sitting silently,” Conradt says. “So I said ‘Cara, don’t be worried about this game.’ She said, ‘I’m not thinking about this game. I’m thinking about what I’m going to wear to the White House.”

From there, the tension of the room broke. Clarissa Davis was magical off the bench, shooting 9/14 for a double-double while Kamie Ethridge dished out 20 assists. Priddy scored 15 in 18 minutes and the Texas bench outscored USC 58-4 while holding Cheryl Miller to 16 points on 2/11 shooting in her final collegiate game. As time expired, the Longhorns had made history in the nascent NCAA.

No. 3 USC W 97-81

34-0. National Champions. The Team of Destiny had done it.

The Days After…

Barbara Jordan was an icon and spoke with an unmistakable cadence. The first Black politician in the Texas Senate after reconstruction and the first Southern Black woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, when she spoke the room stopped.

Late in the evening in 1986, Fran Harris, Andrea Lloyd and the women of UT sat in awe as she introduced the National Champions to their home crowd.

“…and she said ‘when that little Lillie Mason fouled out, it was over for Western Kentucky,” Harris says, in a perfect impression. “To hear her say that it was just like ‘BJ is talking shit in the Erwin Center!’ I’m never gonna beat this in my life.”

Watching their young women bask in the adulation of their fans were Jody Conradt, Chris Plonsky and Donna Lopiano. Everything they built had led to this and while Lopiano probably owed Clark a bottle of St. Emilion because it took more than three years, doing it this way was worth it.

“That was a time you sat back and just had a grin and watching something we had a part in developing,” Lopiano says.

Kamie Ethridge was the National Player of the Year in every major publication. Lloyd was a Naismith All-American and Clarissa Davis — who had finished one of the most dominant NCAA Tournament runs including a 32 point, 18 rebound performance against Western Kentucky and a 24-14 game off the bench in the Title Game — was ready to ascend.

But destiny is a funny thing and a combination of injuries, tough matchups and bad bounces kept Texas from ever reaching the mountaintop again. Davis and Lloyd would suffer knee injuries that would hamper title runs. They would make a Final Four in 1987 before losing to longtime rival Louisiana Tech, who defeated them again in the 1988 Elite Eight. But even without additional titles, the program built by Conradt was noticed by her peers and her players.

“Somebody sets a standard and then everybody else reaches for that,” she says. “Eventually somebody else reaches that standard and sets their own.”

What set the Longhorns apart was a unique demonstration of women in power and what it did for the players that ended up becoming powerful women in their own right.

“Jody Conradt, Donna Lopiano, they were trailblazers,” says Ethridge, who is now the head women’s basketball coach at Washington State. “They need to be put on a pedestal and quite frankly we need to continue to learn lessons for those people.”

“I don’t sometime realize how lucky I am to have been around those people,” adds Lloyd (now Lloyd-Curry), who won Olympic Gold in 1988 and is a Hall-of-Famer. “There was this strangely wonderful atmosphere here with split departments, focused on women, women that were fabulous that drew other women in to really grow young women.”

Lopiano would eventually become the CEO of the Women’s Sports Foundation and was named one of the ‘100 Most Influential People in Sports’ by Sporting News.

“We pursued a very different course of separating ourselves from men’s sports,” she says.

It was that commitment from women, to women, that Harris believes was the key to success and making the Longhorns into the brand they are today, noting that “Texas understood the assignment very early. This is why we are different at Texas.”

And even as other teams, as recently as 2024, have put together undefeated national championship seasons, the 1986 Longhorns will always be first. A team rooted in elevating women, by women who fought for the chance to do it. And continuing to do so today.