Donna Orender could feel the emotion welling up inside of her as her team got into layup lines. All of her memories of basketball, from that first summer camp in Pennsylvania to playing in that park in the West Village, came flooding back. She could see her mother, with a sign that said ‘Go Queens College’, in the stands as lights flashed and a capacity crowd began to cheer. The same arena that was home to Clyde Frazier, Dave DeBusschere and Pearl Monroe now belonged, if only for a night, to Donna and her teammates.

There, a 17 year old college freshman who idolized the New York Knicks stepped towards the basket while ‘I Am Woman, Hear Me Roar’ blared over the speakers in Madison Square Garden. It was at that moment, as the chorus reached a crescendo, that the memories, enormity and emotion came to the surface.

She laid the ball up into a hoop in the Mecca. And she began to cry.

Lucille the First

The story of the ‘Queen’ of Queens College began, maybe predictably, in the borough of Queens itself. It was at PS 141, a public school in Astoria, just a couple of blocks from the terminus of the N and Q subway lines. World War II was just ending and it was at this time that a young Lucille Kyvallos started to become interested in the sport of basketball.

“There were, at that time, recreational leagues, the Police Athletic League and one that was sponsored by a newspaper,” she remembers. “I started playing basketball with the boys and learned all my fundamentals.”

At the time, professional basketball was just starting to find its’ legs as a mainstay in American culture. Led by George Mikan, one the sports’ foundational superstars, the National Basketball Association was formed in 1949. But the resonance of the sport within New York City was already well established and Kyvallos would try to get onto teams where she could.

“My PAL team, we won the city championship and we played in the old Madison Square Garden,” she says. “So that was a big deal back then for us.”

She was recruited to play on a team called the Bronx Angels, founded her own squad called the Queens Rustics and joined a barnstorming tri-state area outfit called The Cover Girls that would play men’s teams in fundraiser events.

But the catch was that Kyvallos and her peers were viewed by the general public as something of a parlor trick. She and her teammates took their basketball seriously but the belief of the time was that women’s sports was a recreational activity. The idea that it could be more than that had been fought tooth and nail for decades, mostly in the 1930’s by the Women’s Division of the National Amateur Athletic Foundation. Through most of that era, New York remained an enclave where competitive basketball was still an option for school-age girls. Other states, like Ohio and Kentucky, weren’t so lucky as bans on interscholastic competition lasted until the federal implementation of Title IX in 1972. Those kinds of inconsistencies created problems with how to address women’s basketball as a viable professional product at home and abroad.

“My desire, when I started coaching, was to show or demonstrate that women could be competent athletes,” Lucille explains. “I never had an opportunity to play for a national team or go to the Olympics and Pan-Am games. Opportunities were very sparse for me at that particular level but I was outstanding.”

Without that outlet to advance her career, Kyvallos decided to finish up her undergraduate degree at Springfield College and then head to the University of Indiana for grad school. She had a keen interest in human kinetics and movement, an area of focus that would prove to be transformational later. The journey then took her to Rhode Island where the Rams had, as it happened, a women’s basketball team. Unfortunately for Lucille, they also already had a coach.

“I was there a couple years and I decided I wanted to get out of there and go to a phys-ed school that had a women’s basketball team that I could maybe get involved with,” she says. “I went [to West Chester] and I was pleasantly surprised.”

West Chester State, the small school just outside Philadelphia, was known as a college with a good physical education program and Kyvallos quickly found that the girls on campus had a bit of a background in basketball.

“They could dribble, they could shoot, they could pass the ball,” she remembers. “We had a record, I think, at West Chester, of 54-2.”

But eventually home started to call. Lucille had lived in New York, Massachusetts, Indiana, Rhode Island and Pennsylvania all before her 35th birthday. It was time to head back to Astoria, to the parks of PS 141 and to the borough that built her. It just so happened that, right when she was looking, there was a faculty position open at Queens College in Flushing. She headed back to the borough and, for two years, taught at the school.

Then, in 1968, the time finally came. The head coaching position came open and Lucille jumped at the opportunity.

A Pearl, the Parks and a Promising Future

While his legacy remains incredibly complex, the famed (or infamous) New York City urban planner Robert Moses did inadvertently become something of a patron saint for basketball in the city. Within the hundreds of playgrounds and public parks built across the five boroughs, many contained blacktops or full on courts. By the 1960’s, what would one day be called Rucker Park was an emerging center of ‘streetball’ culture and a summertime staple in Harlem.

This extended out to Queens, Brooklyn, the Bronx and Staten Island. It’s where young women like Debbie Mason would find chances to play basketball.

“I grew up in the Woodside Projects,” Debbie recalls. “So it was this center court there where it was the main basketball court but you had to be good to play there.”

As an elementary school student, Mason wasn’t allowed to play physical sports so she would instead play bumper pool after classes with her sister.

“How boring!” she jokes.

Something like basketball was more her speed. She watched the boys do it and was interested in learning for herself. So for hours as a kid, Debbie would sit on the sidelines in that center court of Woodside. She would watch, learn, ask questions and wait for someone to get injured so she got a chance to play. Quickly, she picked up on the hallmarks New York City streetball culture that were starting to become embedded in the men’s game: improvisation, flashy passing and toughness on both sides of the ball. It’s how she would get a nickname that would stick with her forever: Pearl. An homage to Earl ‘The Pearl’ Monroe of the New York Knicks.

Elsewhere around the boroughs, Debbie’s story was becoming one of many. Just down the road in the Queens neighborhood of St. Albans, Gail Marquis was becoming a standout basketball player for Andrew Jackson High School. Donna Orender was taking the train from Long Island into the city and playing at parks in the West Village of Manhattan. Cathy Andruzzi was dominating girls catholic high school basketball in Staten Island.

All of them eventually found themselves in Flushing, playing for Coach Lucille Kyvallos.

“Coach Kyvallos was beyond her time,” Cathy says of her head coach. “She was a technician. It was about performance.”

“She was fierce and committed,” adds Donna. “We were athletes and she was smart and she pushed us. It was not easy. It was hard. But you know what? Hard’s good.”

Almost immediately, the success on the floor became apparent. In 1970, Queens College held a Women’s Invitational Tournament where the team finished in third place. The following season, Kyvallos guided the team to a 23-4 finish and an invitation to what was called the CIAW Tournament. But in 1972, everything changed with the stroke of a pen in Washington D.C.

If there was ever a time to create opportunities for the next generation of women, this was it.

The Queens Begin their Reign

That 1971 CIAW trip was a formative experience for the Queens College women’s basketball program. It motivated the players to come home, get better and eventually beat the likes of West Chester, Cal State Fullerton and Mississippi College for Women. But it motivated Kyvallos in a different way.

“I submitted a bid for [the] 1973 [National Tournament]”, she says.

In between those two years though, a seismic change occurred in American sports. Title IX legislation had passed and all over the country, universities were beginning to establish women’s basketball programs if they hadn’t already. The Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, or AIAW, was formed and many of the 60’s power programs — West Chester, Mississippi College for Women and Cal State Fullerton, to name a few — charged out of the gate.

Immaculata shocked the world in 1972 by upsetting West Chester and winning the first AIAW National Championship. Queens competed in that tournament but lost in the first round to Phillips University out of Oklahoma. With a consolation bracket win in hand, focus quickly turned to 1973 and an AIAW tournament that would be held in Fitzgerald Gym in Queens.

“I was the director of the Tournament,” Kyvallos explains. “I had a committee and I’m coaching at the same time and it was very time consuming for me.”

But in spite of the split duties, Queens managed to perform well. They breezed through the New York state playoffs and the Northeast Regionals. Then came the big one: a national 16 team bracket in their home barn.

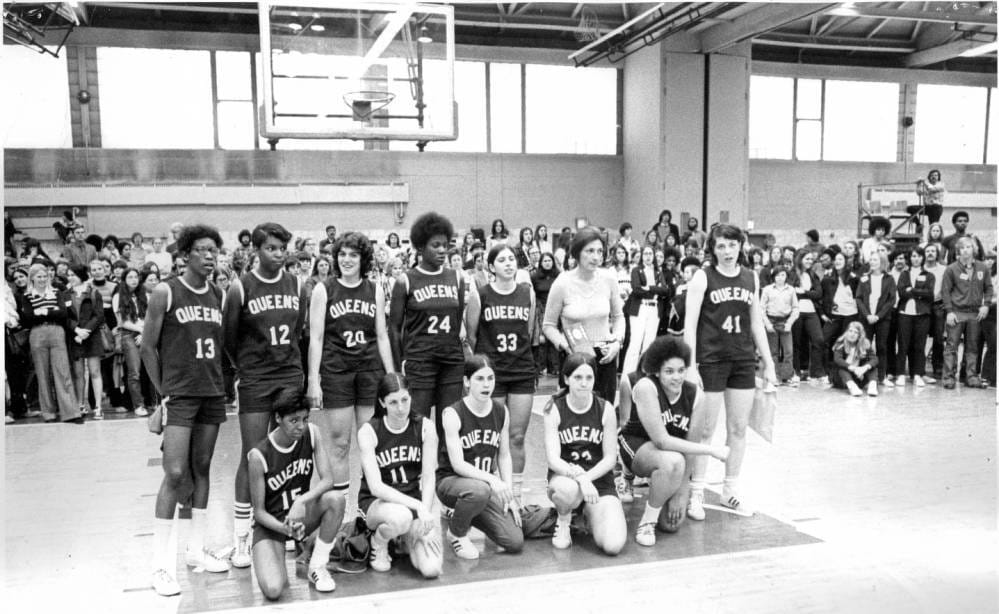

“The gym was full,” Gail Marquis remembers. “It had media coverage from the local newspapers. They moved the bleachers closer to the court so it kind of gave you that arena feeling that you had fans behind your seats or behind the bench as well as the front.”

Queens made it through Stephen F. Austin in overtime and then dominated Indiana in the semi. Now came a national title matchup with Immaculata, the reigning champion.

“It was magical,” Debbie recalls. “They had our college professors and doctors. They were elbowing people so they could get a better spot standing on the sidelines. I had never seem them in that light!”

In a packed gym of 3,000 people, preconceived notions about decorum went out the window. Medical doctors chanted and stomped their feet. The Bucket Brigade — the famous fan section of nuns and Immaculata faithful banging on buckets with wooden dowels — were on hand.

“You could feel people close to you,” says Gail. “I could feel all the nuns in the first row with their habits on. And you want to be respectful, because they’re nuns. But in the same token, I don’t think they were praying for me or wishing me well!”

Immaculata ended up winning that game but Kyvallos didn’t hang her head. Her underlying goal, a bigger objective that went beyond hoisting a trophy, had been accomplished.

“It was such a novel event that it was covered by virtually every newspaper and some TV stations,” she says. “And this went out all over the country.”

With the hope of leveraging the New York City media machine and its’ status as the biggest market in the country, the 1973 AIAW was a strategic bet by Kyvallos that paid off.

It’s A Long Way From Bloomers and Blushes, read Steve Cady’s write up in the New York Times a day later.

Almost overnight, the reputation of Queens College and women’s basketball changed from one of curiosity to one of respect. In 1974, Fitzgerald Gym packed out again to see a rematch of Immaculata vs. Queens in the regular season. This time, Kyvallos and her team defeated the Macs and stopped their winning streak at 57. The crowd rushed the floor and the news went out on wire services nationwide.

Shortly thereafter, she received a phone call from Rob Franklin at Madison Square Garden.

“He wants us to play one of our home games there,” says Lucille. “And he said ‘you can select whoever you want to compete against.”

There was no question in her mind. Immaculata, the top team in America and the best women’s hoops had to offer, was coming back and this time to the Mecca of basketball.

Smelling the Flowers in the Garden

Donna Orender wiped the tears from her eyes and got ready to play. She had a big assignment on that February afternoon in 1975. Guarding Marianne Stanley (nee Crawford) wouldn’t be an easy task for a 17 year old who was just getting her feet under her. But if anything would carry her, it would be the energy exuding from the walls of Madison Square Garden.

“The enormity of it, I felt it throughout my whole body,” Donna says. “It was extraordinary.”

The moment wasn’t lost on anyone. For a group of young women who grew up on the New York Knicks — on Walt Bellamy, Clyde Frazier, Willis Reed and others — it was a validation that the girls were just as much basketball players and those guys were. Gail Marquis got in for shootaround with her teammates and worked on her shot, pivoting and pulling up, trying to mimic Dave DeBusschere’s post moves. But out of the corner of her eye, she noticed the legendary Marquette coach Al McGuire talking with Coach Kyvallos.

“That was one of the times I felt like ‘wow. I really made it to the Garden,’” she remembers.

For Debbie Mason, who was now known as ‘Pearl’ or ‘Little Pearl’ Mason all over New York basketball circles, it was surreal.

“We actually had the shootaround there, walking on the Garden court,” she adds “and it’s like ‘do you think you’re in a dream'?”

As her players took everything in, Kyvallos was thinking about something else. She had played in the old Garden and, after some time in the wilderness of women’s sports, it felt as though her work of creating opportunities she never had was coming to fruition at long last.

“I saw it as an opportunity to enhance the perception of women,” says Kyvallos. “I got sick and tired of hearing boys say ‘you throw like a girl’. And I wanted to show that girls and women could be proficient athletes.”

Much like the AIAW National Title in 1973, Immaculata got the better of Queens. But also like that 73 matchup, the lasting impact went far beyond the result for Lucille.

“After the game, I allowed myself to take a deep breath,” she recalls. “We lost this game but this has historical implications and it’ll change the society.”

The next morning, atop a story about Reggie Jackson’s contract arbitration and next to a write up about the Knicks, a story headed the New York Times once again.

Women’s Basketball Draws 11,969.

The headline underscored the importance of the event. The women’s game nearly sold out Madison Square Garden. The companion men’s game didn’t eclipse 5,000 fans.

“That was a major breakthrough and it alarmed the NCAA,” says Lucille. “They didn’t like what was going on and that’s when they got into developing the women’s program.”

It was a seminal moment and, as Donna would say years later, a clarion call to other programs around the country that it was time to get to work. The women of Queens College would be interviewed by the New York daily newspapers and were even honored at Shea Stadium, a place where most of the players would spend their summers selling peanuts and ice cream. Soon, streetball culture came calling and the Queens players would hang and play with NBA and ABA stars everywhere from Lennox Avenue to Roberto Clemente State Park and Rucker Park itself. Pearl Mason even got to meet *the* Pearl: Earl Monroe.

“I was glad that he didn’t mind, he let me use his name,” Debbie jokes.

As the years continued, Queens continued to excel but a national title remained elusive. Mason, Marquis, Andruzzi, Orender and Althea Gwyn all graduated and in 1981 — the same year the AIAW officially gave way to the NCAA, effectively ending the first era of post Title IX women’s basketball — Kyvallos retired as head coach. Her final career record was 239-77. But more than any national title her legacy is traced through her players, who took up their coaches mission and expanded on it in ways she could not have ever imagined.

Lucille’s Lasting Lineage

Gail Marquis admits she had some complex feelings after finishing up at Queens College.

“I wasn’t done with the game after four years,” she reveals. “[I was] disappointed, frustrated, angry there wasn’t more. I had done four years of college and it’s all over and there’s no place to go.”

The only options available were in Europe or in one of the fledgling leagues in the United States. But even those weren’t a surefire proposition. Pearl Mason played for the New Jersey Gems of the Women’s Professional Basketball League but it didn’t last very long. Her former Queens teammate Althea Gwyn played for the New England Gulls and was part of a franchise protest because players weren’t being paid by team ownership. The WBL folded in 1981.

The story was the same for Cathy Andruzzi and Donna Orender. But instead of letting that frustration stop them in their tracks, over time all the QC alums decided to channel it the way that their mentor did: by helping uplift a new generation of women.

Cathy went to East Carolina University and took over the women’s basketball program. Her coaches show on WNCT-TV in Greenville, North Carolina was one of the first ever for a women’s basketball coach.

“I learned from Coach Kyvallos that if you’re prepared, and you prepare well, and you have a goal in mind, don’t let anybody get in your way of achieving that goal,” she says.

After ECU, Andruzzi embarked on the leadership and performance circuit working with Rutgers University and other multinational corporations. In many cases, Lucille’s lessons permeate Cathy’s work and ethos on what it takes to be successful.

Donna catalogued her time in the WBL in an article in the New York Times titled ‘Making a Dream Come True, and Watching it Fade Away.’

For years after, she worked in television production and spent 17 years working with the Professional Golfer’s Association. She was the original producer of Inside The PGA Tour and helped negotiate the first major TV contact for the organization.

In 2005, she was given her chance to make a dream come true and, this time, keep it from fading away. The WNBA announced her as the second president in history, taking over from Val Ackerman. The league’s eight year contract extension with Disney/ABC/ESPN negotiated under Donna was the first time ever that franchises would receive money via broadcast rights fees. This past year, the newest agreement was reached by current commissioner Cathy Engelbert: $200 million per season and it can even be argued that that figure is still an undervaluation.

Recently, Donna sat in the Barclays Center and watched the New York Liberty win a WNBA Title. As Breanna Stewart, another New Yorker albeit an upstater, hoisted the trophy, Donna thought back to a 1975 night in Madison Square Garden.

“It really puts me back in the place of really recalling that we were badass, hard working athletes at the top of our game, competing at the highest level,” she says.

Gail went to Wall Street and became a high level executive in the financial services industry. In 2009, she was the first woman of color inducted into the New York City Basketball Hall of Fame and has served as a trustee for organizations including the Women’s Sports Foundation and the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women. Much like her Queens College mentor before her, Gail took her lack of opportunities and now entrusts the next generation with taking the baton and running with it.

“I started to realize that my role wasn’t to be the four time All-American, or the four time Olympian,” she explains. “My role was to hold a place for them, to make people of women, the strength of women, to give young girls a place and something to reach for.”

“They can take the space now and hold it,” adds Gail. “You better not let this league fold. You better not let these salaries drop. They have their role as well.”

Even those who returned home — those like Debbie Mason and Althea Gwyn — found work that helped and uplifted people in their own communities. Gwyn, who passed in 2022, worked for the Fayetteville, North Carolina fire department. Debbie works with the New York City Department of Education.

In every case, the connective tissue for all these women in power is Lucille Kyvallos, who hasn’t lost a step in the slightest. At 92 years old, she’s still a competitive tennis player in Florida and is in regular contact with her former players. The reverence with which they speak of her is only eclipsed by their passion that she receive the credit she deserves. In spite of her contributions to the game, Kyvallos has been nominated but not inducted into the Naismith or Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

“I hope you print this,” says Donna. “The fact that she has not been enshrined in the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame is criminal. She was a pioneer of pioneers.”

“She never got the recognition in terms of being one of the greatest coaches but also innovators of the game,” adds Cathy. “She was iconic. She did a lot for the game.”

It’s a common through line from everyone that went to Queens and is still around to speak on it. Lucille Kyvallos was, and is, a central figure for change even if she views herself as a tool for greater cause. Her players don’t want to see her story fade as the AIAW has increasingly become a footnote in a collegiate history told by the victors: the NCAA. Instead, they see her impact in New York’s basketball culture which has produced hall-of-famers like Chamique Holdsclaw, current WNBA stars like Tina Charles and future phenoms like 2026 Five-Star recruit Olivia Vukosa.

And even as the new generation of WNBA and NCAA players take center stage, there will always be an echo of Queens College in each sold out arena or front page headline. A whisper that reminds them of Lucille Kyvallos and the Queens in Queens. Those who laid down the ladder, offered a hand up and continue to do so in ways that may not jump out at you but can be seen if you know where to look.

Thanks for reading No Cap Space WBB! This post is public so feel free to share it.