The Legendarium: The Last Champions

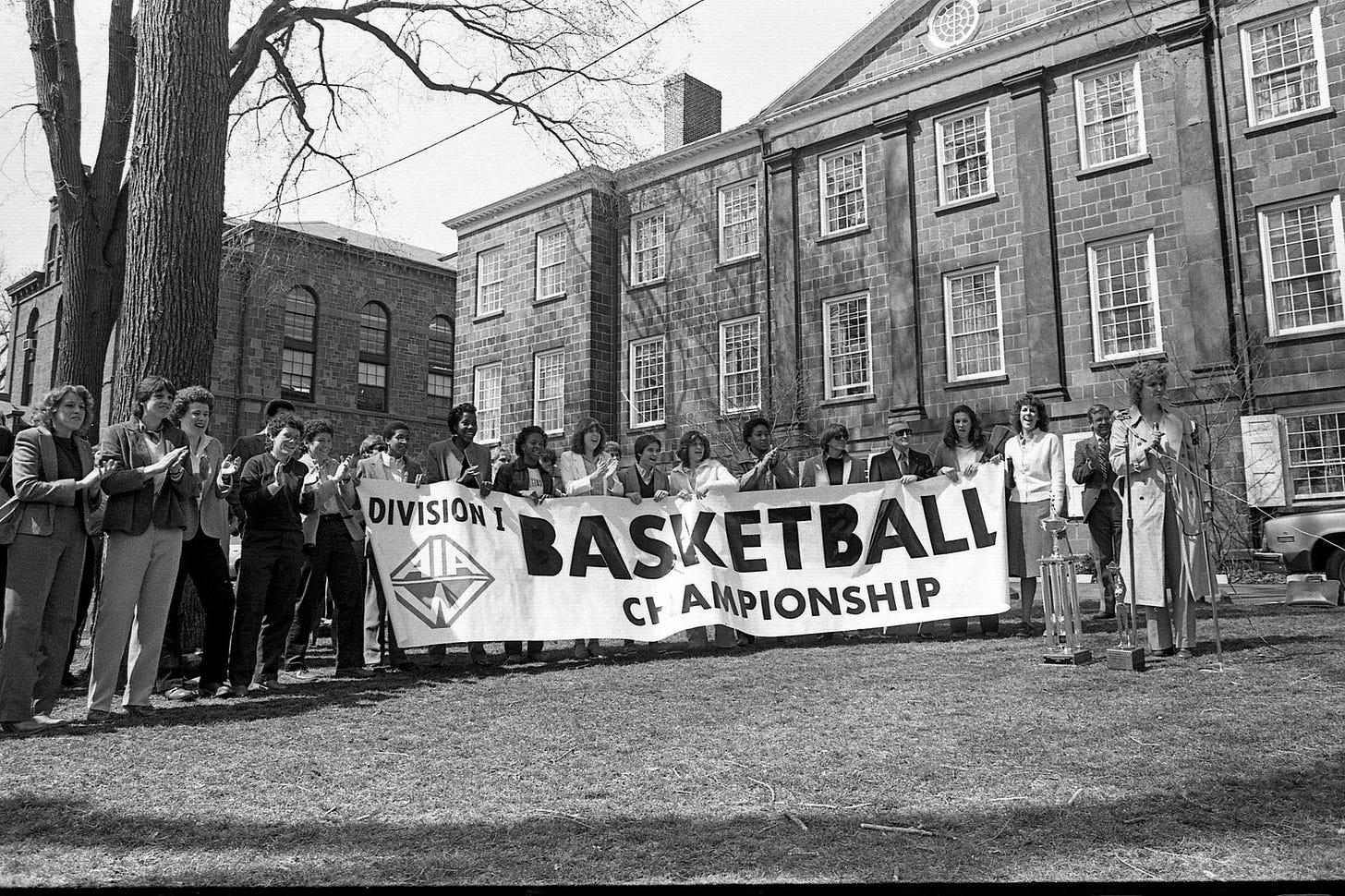

Rutgers won the 1982 AIAW Women's Basketball Tournament, the final chapter of a foundational era of women's hoops. Now they hold a special distinction in the history of the sport.

Good Shepherd was Mary Coyle’s church but The Palestra was her cathedral. A monument made of steel and concrete, gothic in style. Every seat had a view. Every player could feel the weight of nearly ten thousand voices bearing down on them when the arena sold out. A venue that felt as alive as the players running the floor.

As she prepared to play, Mary wasn’t sure how she’d be received. For years, she and her twin sister Patty had been viewed as renegades or, even worse, traitors. The recruits who had spurned Philadelphia for New Jersey. But now, on a holy Sunday in 1982, she looked up into the stands of The Palestra and saw a banner that stood out in a sea of Rutgers red.

“Welcome home twins.”

There, in the 1982 title game between the Scarlet Knights and the Texas Longhorns, the Coyle sisters were home. And they were going to win the last national championship.

All Roads lead to Philadelphia

The night before, Mary had been restless. Head coach, Theresa Grentz had told her plainly: ‘don’t even think about coming out’. Texas was too good and she’d need to be on the floor every minute if they wanted a shot to win. So she went to Finnegan Playground with Patty and another teammate, Jennie Hall, for a pickup game.

“I played for about an hour and a half, two hours,” Mary remembers. “It was familiar. It was a way to combat the nerves and I guess it was more just trying to get the excess energy out of me.”

It was a calming, familiar routine. The Coyle sisters had grown up on those blacktops. A lot of the Rutgers players did. Philadelphia was, at that point in history, something of an incubator for women’s basketball legends, renowned for producing some of the best players of the era. The Big Five — Penn, La Salle, St. Joe’s, Villanova and Temple — played all their games at The Palestra, which doubled as a championship venue for high school players in the city.

“If you look at all the Division I players that came out of a four year span, it would be ridiculous,” Patty says of the Catholic League. “I’m not talking 5-10 players. I’m talking 35 Division I players. And that was shaped a little bit by Immaculata.”

The first dynasty in women’s basketball was from Philly. Immaculata won three national championships in the early 1970’s. They took the baton from West Chester University, a college just down the street, who had already won a 1969 title in the CIAW, the AIAW’s predecessor. The star of that team was Marian Washington, who would later become the first Black head coach in women’s basketball and a hall of fame inductee. A 30-minute drive east of West Chester, a young college student who called himself ‘Geno’ was coaching the Bishop McDevitt high school girls team and over at Archbishop Carroll, a 22-year-old named Muffet O’Brien was starting her coaching career while preparing for a wedding to Matt McGraw.

Among the catholic populations in Philadelphia, the small school was the spark. The Mighty Macs’ three AIAW championships turned them into a household name and made Theresa Grentz (nee Shank) a superstar among the high school girls in the dioceses.

In the coming years, Immaculata’s star players became some of the biggest coaches in college basketball. Rene Portland (nee Muth) spent two seasons at St. Joseph’s and two at Colorado before landing at Penn State. Marianne Stanley (nee Crawford) was just 23 when she took over for Pam Parsons at Old Dominion. Grentz went to St. Joe’s where she balanced teaching elementary school and coaching. But eventually, the AIAW (short for the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women) demanded that schools get serious if they wanted to compete in a new scholarship era. Rutgers came to Grentz and offered her an opportunity: become the first full-time head women’s basketball coach in the United States. Despite her allegiance to Philadelphia, she knew that Piscataway was close enough to provide what she was looking for.

“Rutgers had a full time position and they offered it to [Immaculata head coach] Cathy [Rush] and they offered it to [Queen’s College head coach] Lucille Kyvallos and they both turned them down,” Grentz recalled. “And Rutgers offered me the job. And I went there and I was gonna win a national championship.”

When Mary and Patty heard about Theresa’s move from St. Joe’s to Rutgers, the choice was easy. It didn’t matter what other schools were recruiting them out of high school. They had a singular destination in mind.

“We were gonna play for her regardless of where she was,” says Patty.

The Rise of Rutgers

Grentz’ office had a secret door that led straight out into the Rutgers Athletic Center arena. Players would often tell security guards that they had team meetings at strange hours and had to abide by their coaches’ wishes. In reality, they’d sneak through the door and see everything from men’s basketball games to Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes.

“I don’t know why they thought we had a team meeting in the middle of a concert,” says former team captain Chris Dailey with a laugh. “You have to act like you know what you’re doing.”

“It was probably an NCAA violation back then but who cares now?” Grentz adds jokingly.

After all, the rules back then were…malleable. In 1978, Sports Illustrated’s Kent Hannon lamented the fast and loose recruiting style associated with the AIAW. The University of Kansas had been investigated over improper benefits given to a Nebraskan phenom named Lynette Woodard. In the very same article, Theresa was mentioned as one of the three coaches vying — and potentially violating AIAW rules — for the services of a talented forward out of St. Maria Goretti High School. June Olkowski was the type of player everyone rolled the red carpet out for but there was only one school she had in mind.

“In the back of my mind all along, I think I always wanted to play for [Theresa]”, June says.

So Olkowski went to Piscataway and when she arrived she saw the makings of a special team. Herself, the Coyle twins, a community college transfer named Terry Dorner, Jersey kids Chris Dailey and Patty Delehanty (nicknamed ‘Ladybug’) as well as Norristown native Jennie Hall made up the roster. It wasn’t the most talented team in that four year span but it had the best chemistry.

Over the next few years, the Scarlet Knights started to find success on the floor. In 1978 and 1979, with Patti Sikorski and Kathy Klutz as captains, the team went on a 28 game home winning streak and managed to upset historic powerhouses including USC, Cheyney State and Maryland. Like many teams of the time, they were something of a traveling road show. They faced off against Lynette Woodard’s Kansas team in the Orange Bowl. When the Meadowlands Arena opened, Patty was given the task of guarding UCLA guard Jackie Joyner. Louisiana Tech, with Janice Lawrence anchoring the front court and a plucky guard named Kim Mulkey commanding the floor, was always a thorn in Rutgers’ side but one of Mary Coyle’s favorite matchups. For years, they met in Madison Square Garden to face off.

“She’d probably say I was the meanest son of a bitch she ever played,” Mary says about Mulkey with a laugh. “And I’d tell her, ‘you were no prize either!’”

Each season, they got close but came up short in the AIAW Tournament. One year they were bounced by Tennessee, the next it was Old Dominion and then Long Beach State the year after that.

“The success we had [in 1982] really started the year before and was probably based in disappointment,” explains Dailey. “We did have a much more talented team that didn’t reach its’ potential.”

But it was those kind of matchups that the Rutgers players loved. In those days, problems were solved on the floor and everyone had a chip on their shoulder. In 1982, following a win over Cheyney State, the Knights headed down south to play South Carolina. At that point in time, the Gamecocks had been rocked by controversy. Pam Parsons had resigned, unresigned and was entrenched in a scandal that would eventually rip at the very foundations of the sport. Tensions were already high and the Coyles were known as tough matchups for opposing guards. When a South Carolina player dropped a ball into the lap of Patty, she threw it back. It hit the player in the face and the chippyness of the game turned into something else. Benches cleared in Columbia.

“Ladybug got punched in the face,” Olkowski remembers. “And they were waiting for us after the game and Chris Dailey said ‘oh please. We’re already dressed up. It’s a game. Move on.’”

“If you knocked them down or did something, they weren’t coming to me crying,” adds Grentz. “They had their own kangaroo court. They handled it on the floor.”

That’s just the way it was back then. South Carolina got the better of Rutgers in that matchup and the rest of the year was a mixed bag. June, widely regarded as the top player in the nation in 1981, had been dealing with a knee injury throughout the season and it took a toll on her mentally. After a loss to Villanova in the AIAW East Mid-Region Tournament, it finally came to a head. She headed up to Theresa Grentz’ office to suggest a change.

“I said, ‘I will step back,” she says. “I hurt us. I didn’t do anything to help us and if we’re gonna do what we wanna do, I’ll step back and just be support. You don’t have to play me.’ And then Theresa, being as wise she always is, said to me ‘you’ll find a way to help us.’”

While Rutgers beat Tennessee in January, they lost to some of the elites that season. Cheyney, Maryland and Old Dominion came into Piscataway and left winners. There was some question about how good the Knights could be and where they landed in the national conversation. But soon, it wouldn’t matter. There were other, larger forces at work and, be it by divine providence or something else entirely, Rutgers ended up right where they needed to be.

The NCAA crashes the party

The world was ready to split in 1981. After ten years under the auspices of the AIAW, women’s basketball attracted the attention of the NCAA. Since the inception of Title IX, governance of the game had existed on an island unto itself. Its growth felt exponential and, more importantly, it belonged exclusively to women. Administrators, from Texas’ Donna Lopiano to legendary Iowa Athletic Director Christine Grant, advocated fiercely for the AIAW to remain independent of the NCAA and be free of the mistakes the men had made with their sports.

Factions had emerged and, rather quickly, the Fountainbleu Hotel in Miami became a battleground in 1981. The NCAA was deciding on whether or not they wanted to hold championships for women. Some, like NC State’s Nora Lynn Finch, saw sanctuary in the NCAA’s connections and infrastructure. While others believed that the AIAW had gotten to a point that it could stand on its’ own. Just a year prior, in 1980, the women’s basketball national championship was said to have outrated some NBA Playoff games on TV.

So they put it to a vote. The story goes that the AIAW had won by a single ‘aye’ on a recount. But, allegedly, the NCAA was able to use the University of California to introduce a motion to reconsider. When the motion passed, the NCAA won. They promised transportation support, no increase in dues to add women’s programs and a subsidy of the women’s championships. NBC, which was three years into a four year contract with the AIAW, pulled out of their broadcast agreement citing a loss of highly visible competitors. $250,000 swung from one league to another. The NCAA Title game would be on NBC. The AIAW championship wouldn’t be televised at all.

Texas, undefeated and ranked fifth in the nation, was a foundational member of the AIAW. They weren’t going anywhere. C. Vivian Stringer, coaching No. 2 Cheyney State, would say decades later that she preferred to stay the course one last time but that the transportation subsidy couldn’t be passed up by an HBCU that was already operating on thin financial margins. Grentz talked with her own athletic department and the determination was made.

“I had nothing to do with that,” Grentz recalls. “I would have preferred to go [to the NCAA Tournament]. But knowing that, looking back now, this was supporting women and the AIAW, what they were doing. I think it was right. So I supported the decision back then.”

There was a sadness in their solidarity. Title IX felt in some ways like a grand irony now. In giving more opportunities for women’s athletes, it stripped women of the chance to govern themselves.

“In the hay days back then, the AD’s had their own boys club,” Grentz adds. “They didn’t want another set of rules.”

But while Cheyney, Tennessee, Louisiana Tech and others went onto the NCAA Tournament, plenty of firepower remained in the AIAW. Texas, Delta State, legendary program Wayland Baptist and Rutgers were the biggest draws. It was the last dance for some of the 70’s greatest power teams. But the Knights didn’t intend to fade out as Immaculata had or Wayland was about to. It may have been the final title chase in the AIAW but the hope was that it would only be the first of many in Piscataway.

The last champions make their run

While some around the program may have wished they were going to the NCAA’s, the Philly girls, in particular, didn’t care. Texas was still competing in the AIAW tournament and they were a top 5 team nationally, undefeated behind one of the most dominant rosters of the time. Rutgers wouldn’t be playing pushovers. And, best of all, they got to go home. The Palestra, the iconic home of the Big Five and the unofficial capitol of college basketball, was calling and the opportunity to hoist a title in their city was all the motivation that was needed.

“You can’t go leave Philadelphia and not come back and win it,” Patty says.

The Knights had already beaten a Philly opponent, Villanova, to get to the finals and now they happened upon a dominant Texas team. The day before the game, the Longhorns walked out in their burnt orange warmups, lined up shortest to tallest. Mary thought it was an intimidation tactic. Patty, who had seen them up close earlier in the week, wasn’t so sure.

“I can remember walking down the bleachers and Texas was walking up and I remember thinking, ‘how in the hell are we gonna beat them?’” says Patty.

That Sunday it was sweltering in the locker rooms. Every hallmark of a classic in the cathedral of college basketball was present. A good crowd, a grand building, two elite teams and a room temperature that was going to test everyone’s mettle.

“I remember thinking ‘Jesus! I’m gonna sweat to death before I even get out on the floor!” Mary says.

Mr. Coyle couldn’t bring himself to watch the game. For years, his friend — a security guard for The Palestra — would open the back door and let him and his daughters come watch Big Five games. Now, the stress of seeing them on that very floor was too much to bear. From start to finish, one of the Coyle girls that wasn’t playing had to run up to the concourse during timeouts, call him and give him a score.

Texas went ahead early in the game and stayed there going into halftime. At the start of the third quarter, their five point 39-34 lead was their largest. Olkowski, feeling a repeat of her ‘0fer’ performance against Villanova was subbed off and walked to the bench.

“I came off the floor and I was frustrated and I said ‘I can’t hit the broad side of a barn’,” June recalls. “And [Chris] said ‘yeah, we noticed. You better start rebounding.’”

While the words came from Dailey’s mouth Olkowski could hear Theresa Grentz, sitting across from her in that cramped office, doling out wisdom nearly a month earlier.

“You’ll find a way to help us.”

So June snatched boards, Terry Dorner poured in 25 points while Patty’s 30 was a career-high. The twins ran the show, with Mary playing every single minute.

“She had pressure on her for 40 minutes and doesn’t turn the ball over,” Patty explains. “That was a pretty good team and Mary had control of [them].”

No one believed it happened until the final buzzer sounded.

83-77.

Texas was undefeated no more and Rutgers were national champions.

Knights in Scarlet Armor

After hoisting the trophy, the Knights went out to dinner. Grentz and her husband maxed out two credit cards to give the kids a meal to remember. The athletic department probably wasn’t going to let them expense the meal but she didn’t care.

While Rutgers walked away champions, the other Pennsylvania team in a national championship — C. Vivian Stringers’ Cheyney State — fell in the NCAA final. It had been a hard couple weeks for Stringer, whose daughter Nina had been struck with spinal meningitis just before the Final Four. With a few days of downtime in Philadelphia ahead of the AIAW matchups, Dailey and Olkowski decided they’d support a fellow basketball family. So they bought a stuffed animal, headed over to Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, sat and played with little Nina and talked with Bill.

“We had such respect for Coach Stringer and Cheyney State. We had some big battles but when it comes to your children and your family, it’s a whole different ballgame and we just wanted to go over and be supportive,” June would say later.

“It’s more than basketball at that point,” Dailey adds. “That’s not something you want anyone to have to go through.”

It was a perfect encapsulation of the program Grentz had built. A personification of a bond that was built on basketball and a sorority solidified by competition. It didn’t matter that Cheyney and Rutgers had battled earlier that year, or years before. It didn’t matter that one was in an AIAW title game and the other was in the NCAA. Everyone was a part of the collective and everyone received support.

13 years later, Grentz prepared to leave the program that she built. Rutgers had become synonymous with success in women’s basketball. Since joining the Atlantic 10 in 1983-1984, they’d won the conference eight of the last 12 years. From 1985 to 1993 they made the NCAA Tournament every year, punctuated by two Elite Eight trips. In order to maintain what she had created, Rutgers leadership needed to find a proven winner. Someone who knew the area, the program, and how to tap into the fertile recruiting ground that built the backbone of its most successful team.

On July 15th, 1995, C. Vivian Stringer held court in front of media members. With Rutgers preparing to move into the Big East and to stand against an emerging juggernaut from Storrs, Connecticut, things had come full circle again. Much like Grentz took success from Philadelphia and brought it to Piscataway, Stringer was about to do the same.

“I want a winner and I’m going to be a winner,” she said that day. “I just know that Rutgers will be the jewel of the East.”

Forgotten champions, forgotten no more

It took almost forty years for Theresa Grentz to find out about Mary’s trip to Finnegan Playground the night before the national championship. And, needless to say, she wasn’t too pleased. Risking injury on blacktop pickup before the biggest game of their careers at that point?

“I almost killed them,” she says with a chuckle.

Over the course of multiple decades, the teammates stayed close and in consistent contact with one another. New players like Sue Wicks came in just a couple years after the 1982 season and became new standard bearers. Multiple Rutgers grads ended up in the WNBA while others became coaches. Patty Coyle played and coached for the New York Liberty. June Olkowski is the only coach in Butler history to never record a losing season. Mary Coyle, now Mary Klinger, is one of the greatest coaches in New Jersey high school history and Chris Dailey has sat by Geno Auriemma’s side for many a championship. Wherever she can, makes a point to introduce her new UConn players to the history paved by herself and those like her.

“You have to go back and appreciate what people before you did as part of history before you can, I think, take your place in history,” explains the 11 time champion coach.

The legacy of the Last Champions is built on those that came before. At least that’s what most members of that 1982 team say. As the final standard bearer of the AIAW era, they represent a foundational period of the game. One that was defined as for women, by women. As subsequent generations have entered the fold, won NCAA championships, created dynasties, founded a professional league and brought the sport into the center of the American cultural conversation, they are proud to have played a part in the journey.

“We left it better than we got and it’s following the way you should follow,” Patty says now. “You leave a place better than you found it.”

And while millions tune in to see who the next NCAA champions will every April, there will always be a Last Champion. To some, a footnote in the illustrious history of the game but, for others, pioneers that stood on the shoulders of trailblazers and hold the current generation on theirs.

“You always have to protect the game and whoever’s in it,” Grentz says, wrapping the interview. “And for us, I think we did that.”

If you'd like to read more about the 1982 team, check out Forgotten Champions! It's an incredible documentary done by members of the student media team that covered that group back in the day.

Check out their website Forgottenchampions.com.

What a wonderful article. So much history, grit, and love for the game. I wonder if women’s basketball would be better if they stayed out of NCAA hands. Just remember how little respect they have for the women’s game - facilities etc. - unequal treatment still abounds.